FERC

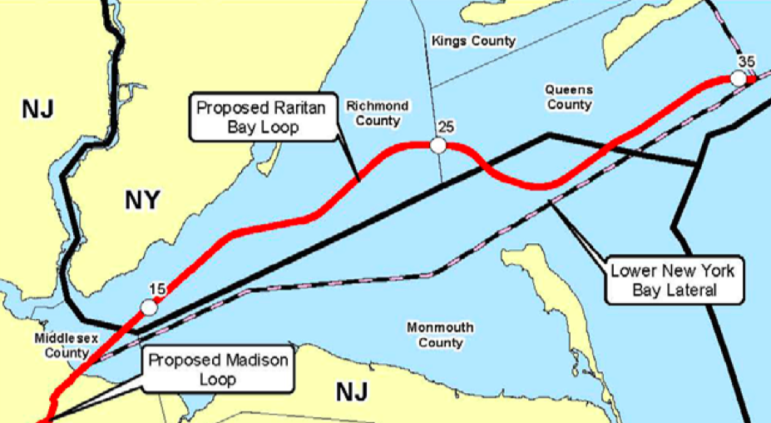

The route of the proposed Williams Transco pipeline.

Opponents of a proposed natural gas pipeline have questioned National Grid’s claim that it needs the new supply to keep up with rising demand. And the utility’s own filings with regulators only add to those questions, which persist even though the pipeline suffered a regulatory defeat on Wednesday.

The Cuomo administration decided Wednesday night to block Williams Transco’s application for state permits to build a 24-mile underwater gas pipeline from the New Jersey coast to a connection with an existing pipeline off the coast of Queens. The Federal Energy Regulatory Commission okayed the plan, known as the Northeast Supply Enhancement or NESE, earlier this month. National Grid had agreed to buy all the gas the Williams Pipeline pumps to the city.

“The state has made it clear that dangerous gas pipelines have no place in New York. This is a victory for clean water, marine life, communities and people’s health across the state,” said Kimberly Ong, a senior attorney at the Natural Resources Defense Council (NRDC). “Instead of further locking in our reliance on fossil fuels, New York is rightly capturing the power of the wind and the sun, and investing in a local clean energy economy. We will continue to work with our allies to ensure this reckless project is shelved forever.”

While some pipeline opponents celebrated the defeat, others were concerned that the application could be revived. Indeed, in a statement released late Wednesday, National Grid said, “Williams will evaluate and address the issues cited in the denial decision and will resubmit the application quickly.”

“We remain cautiously optimistic that the project will proceed on schedule and be in service for Brooklyn, Queens and Long Island customers by the winter of 20/21,” National Grid continued. “Until we have greater certainty around the project’s application approval timeline, we will continue to advise all new commercial and residential applicants that our ability to provide firm gas service is contingent on the timely construction of NESE.”

The New York state permit was one of the final regulatory hurdles facing the proposal. New Jersey’s decision on a permit is due by June 20.*

If National Grid and Williams do mount a second attempt at a permit, it will revive questions about the rationale for the pipeline.

With protests and even a hunger strike, critics of the plan had pushed Gov. Cuomo to turn it down. They argued that a state that has banned hydraulic fracturing or fracking, as New York did in 2014, shouldn’t allow the construction of new infrastructure that would import fracked gas from other states. They’ve also raised concerns about the impact of pipeline construction on wildlife and questioned how a state committed to a “green new deal” could allow new facilities for fossil fuels.

On the other side were downstate utilities, who argued that rising demand for gas is eclipsing the current supply, threatening the existing source of cooking gas and, increasingly, heat for many New York residents. Con Edison, which divvies up the New York City gas-service territory with National Grid, has imposed a temporary moratorium on new gas connections in Westchester County, claiming that supplies are just too stretched to add new hook-ups.

But the utilities never provided detailed numbers to support their claims of looming shortages. Last week, city Comptroller Scott Stringer wrote to Con Edison asking for details; a Stringer spokesman tells City Limits there has been no response so far. State regulators will not weigh in on Con Ed’s Westchester moratorium until early July.

Shifting projections of gas demand

While National Grid provided scant specificity on supply and demand during the pipeline debate, its filings in a different theater offered some detail, if little clarity.

In its 2019 application to the state Public Service Commission (PSC) for a hike in gas rates, National Grid said it saw supply shortages coming, and raised the specter of its own moratorium unless the pipeline was built.

“If the project does not become available by the 2020/21 winter season, the companies will not be able to prudently satisfy new or additional service requests without jeopardizing the companies’ ability to provide safe, reliable service to its existing firm customers,” read testimony by a National Grid officer. “In that case, National Grid will have no choice but to impose a moratorium on new and additional gas service in affected areas to maintain system reliability.”

Yet in the company’s previous application to the PSC for a rate adjustment in 2016, the company predicted heavier usage of gas than has occurred.

National Grid estimated back then that it would deliver 3.9 billions therms (a heating measure) in 2017, yet the company sounded no alarms about pending shortages. Of the possible Transco pipeline, then in the planning stages, National Grid said merely that its benefit would be “further enhancing reliability of the system.”

In reality, the company only supplied 2.6 billion therms in 2017—meaning its projection was off by about 35 percent. (National Grid did have 12,000 more customers in 2017 than it predicted in 2016 rate-setting documents.)

The PSC filings also indicate that between 2016 and 2019, even as it was raising alarms over tightening supplies, the company actually lowered its projections for deliveries in later years.

Back in ’16, National Grid said it expected to deliver just over 4 billion therms in 2018 and again in 2019. Now it has reduced those projections by 31 percent and 30 percent, respectively, to less than 3 billion therms in each year. That doesn’t eliminate the possibility of a supply shortage, but it suggests demand projections have proven less than reliable.

“We have learned the hard way not to take fossil fuel companies at their word. National Grid and Williams have made unsupported claims about need for this pipeline with no proof,” Maria Michalos, a spokeswoman for NRDC, told City Limits. “At the same time, they’re trying to paper over the very serious environmental impacts — for which there is actual data to back up.”

A study commissioned by the activist group 350.org cast a harsh light on National Grid’s claims, arguing that there is little demand for additional oil-to-gas conversions.

The math on that is fuzzy, however: While all buildings using No. 6 heating fuel have converted to better fuels, the total number of buildings burning No. 4 oil or other petroleum blends that might be in a position to seek oil-to-gas conversions is hard to pin dow. The city’s Department of Buildings only tracks large boilers, and says about 20 percent of them (or 25,000) are still oil-operated.

How much carbon reduction is enough?

Both sides of the debate seem to agree that climate change is a dire threat and that fossil fuels are not a long-term answer to the city’s heating needs (or its electrical needs: About half the power in the city comes from national-gas fired power plants).

Pipeline proponents, however, argue that gas is necessary as a transitional fuel. The shift in recent years from heating oils to cleaner-burning gas is credited with improving local air quality and reducing the city’s carbon footprint. National Grid says the Transco project will allow 8,000 customers to switch from heating oil to gas each year, saving 900,000 barrels of oil and 200,000 metric tons of carbon dioxide emissions.

There are questions about those numbers, too. “Even if we take Transco’s assumption that the project would result in conversion of 8,000 customers per year from heating oil to natural gas and displace 900,000 barrels of heating oil per year, it would only reduce the Project’s downstream GHG emissions by a small amount,” Richard Glick, the lone “no” in the 3-1 FERC vote on the Transco pipeline, wrote in a dissent on May 3.

Glick’s fellow FERC commissioner Cheryl LaFleur, who voted to approve the project but articulated some doubts in a concurring opinion, said she calculated that the reduction in overall carbon emissions would be 109,000 metric tons – roughly half of what the company claimed. Overall, LaFleur calculated, the gas in the Transco pipeline would result in 7.7 million metric tons of carbon dioxide emissions—less than if those converted customers were using oil, but still a lot of greenhouse impact.

Any reduction in CO2 is a valuable reduction, pipeline proponents argue, especially when it comes without major disruption to life in the city. “Uncertainty over the energy supply will discourage investment in jobs and housing that the city desperately needs,” the Partnership for New York City, a business lobby group, said in testimony to the City Council earlier this year. “The NESE must move forward immediately.”

But environmental advocates believe the pipeline decision presents an opportunity for the kind of dramatic reductions in carbon emissions that recent scientific studies indicate are necessary to mitigate a climate disaster. They see little justification for locking more customers into a fuel that might not be viable in a few years’ time.

“We have to break the cycle of building fossil fuel infrastructure. As we focus and work aggressively to improve the efficiency of the city’s buildings, we can reduce dependency on natural gas and expedite the transition away from fossil fuels in our built environment, while ensuring New Yorkers have access to affordable heat and hot water,” said Seth Stein, a mayoral spokesman.

* Correction: The original version of this story incorrectly reported that the NY permit decision was the final regulatory hurdle for the project.

12 thoughts on “Doubts About Pipeline Proponents’ Claims of a Gas Shortage”

Actually we need oil pipelines too. Most of the harbor traffic is oil lighters, through the 1980s, 25 percent of the nations oil lightering was in the Port of New York, Tampa was in second place with nine percent.

Yes, we need to end use of fossil fuels, but we can reduce that dramatically with pipelines in the meantime. Oil lighters add two steps where fuel is inevitably spilled. The fuel used in tug, towboats and self propelled lighters is not inconsequential either, not to mention the fuel truck trips around the city which could be reduced as well. Fuel for thought.

You environmental thick skulls, Stopping more natural gas from coming into this area is just going to make everyone burn more crude oil > with higher CO2 emissions and Sulphur oxides and cost. Where do you think electricity comes from? Nat gas ! and when that’s low they burn oil and coal. Nuclear> zero atmospheric pollutants but no one wants that either.

This is a bad idea to restrict natural gas expansion. How expensive things will be if we try to be 100% renewable, maybe we can dam up a few more rivers for hydro power? Or throw up some more wind farms to dice up the wildlife that flies past them. Solar, yes but we should only have electric during the day?

I cant believe the games played on the citizens to restrict gas service expansion.

Welcome to the new world of having less control of doing better things.

Pingback: Another Setback for Plans for a New Pipeline in NY’s Harbor | NYC Informer

Environmental thick skulls, huh? As though renewable energy projects could ever kill as many animals as the oil and gas exploration industries, which are currently leaking methane into the atmosphere at obscene rates from every single stage of their production and supply infrastructure. Beyond that, anything over 3% leakage of methane completely negates whatever marginal GHG benefits we can reap from the switch over to natural gas.

Google recently found that just the ammonia fertilizer industry was dumping out 4 times more methane than the EPA thought was coming from all industrial processes in the United States put together. Methane, the same stuff that natural gas is almost entirely comprised of, warms the atmosphere 100 times more effectively over the short term than CO2, and the burning of which also just produces more CO2. Oil is far from the only option, and as we saw in the case of the now canceled ConEd moratorium, the immediate response was not to go back to oil as the lying natural gas lackeys and blood money thirsty unions sending their own members into incredibly dangerous jobs with stunningly irresponsible companies such as Williams, would have you believe, but to roll out geothermal heat pumps, which, according to the EPA, are “the most energy efficient, environmentally clean, and cost effective space-conditioning systems available, with the lowest carbon dioxide emissions.”

You people are cutting off your noses to spite your face. If you weren’t aware, there isn’t some secret cache of clean air and water set aside for climate deniers. We’re all in this sinking boat together whether or not you’re smart enough to realize it.

Pingback: Doubts About Pipeline Proponents’ Claims of a Gas Shortage | Altresco Companies

Pingback: National Grid Asks Customers to Help it Lobby for a New Fracked Gas Pipeline – Sludge – Texas Nurse Practitioner News

Pingback: National Grid Asks Customers to Help it Lobby for a New Fracked Gas Pipeline – Sludge | @readsludge | Actify Press

Pingback: National Grid to NYC customers: Support the Williams Pipeline or no new service – Enjeux énergies et environnement

Pingback: National Grid to NYC customers: Support the Williams Pipeline or no new service – Philanthropy Media Network

Pingback: National Grid Asks Customers to Help it Lobby for a New Fracked Gas Pipeline – Sludge | @readsludge

Pingback: National Grid Asks Customers to Help it Lobby for a New Fracked Gas Pipeline – The American Prospect – Texas Nurse Practitioner News

Pingback: National Grid Asks Customers to Help it Lobby for a New Fracked Gas Pipeline - Pay Day Loans Online Forum