Manfred Curry, Verlag F. Bruckmann, Flannery Family, Bruce Emmerling

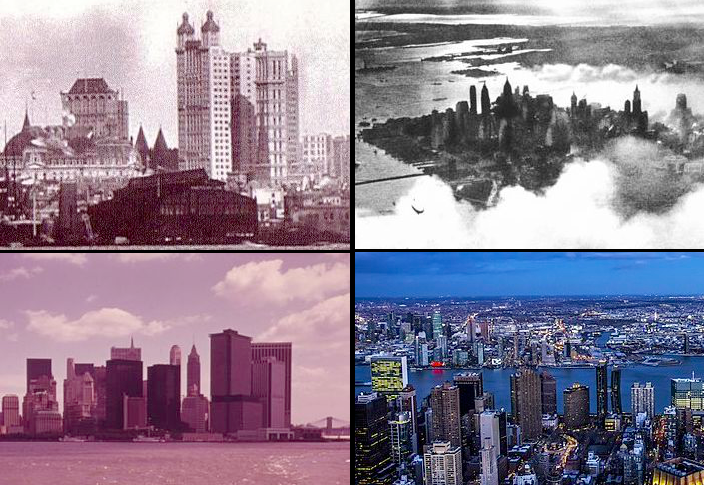

The city in (clockwise from top left) 1902, 1932, 2018 and 1970. The author argues that property owners have helped bring New York’s housing stock to a historic level of quality today.

New York City’s housing market is unlike any other. Apartment development can hardly keep apace with the city’s booming population; tens of millions of tourists flock increasingly to the city’s landmarks, driving demand for home-shares masquerading as rental units; and international buyers, hedge funds, and private equity firms view the city’s real estate as a prime asset class more than ever.

Now, in an attempt to tackle the affordability crisis, our lawmakers in Albany are irrationally focusing not on the macro forces that are making the city so expensive, but on the individuals and companies that have improved the safety and quality of the city’s private rental units for decades.

To chart a better path, my organization – the Community Housing Improvement Program (CHIP), which represents 4,000 property owners that own or manage one-third of the city’s rent-stabilized homes – is proposing a series of policy solutions that will ensure New Yorkers have access to affordable and well-maintained rental homes for years to come.

These proposals are based on the foundation that New York’s housing stock has steadily improved over the past several decades, but that more work needs to be done.

Since the 1970s, the improvement to the city’s housing stock has been a success story. Apartments in good or excellent condition jumped 20 percent from 1978 to 2017. And families that live on blocks with boarded or broken windows decreased by nearly 90 percent during the same period, according to the New York City Housing and Vacancy Survey.

Indeed, this sustained progress stands in stark contrast to NYCHA homes. Whereas private owners, particularly of rent-regulated units, are incentivized to make improvements to affordable homes, NYCHA’s landlord – the City of New York – is not. In fact, according to the Citizens Budget Commission, from 2016-17 private rental homes saw a decrease in physical deficiencies across every single category, including leaks and heating breakdowns. At the same time, problems with NYCHA increased in nearly every category – a vivid display of the human cost associated with disinvestment in New York City housing.

And now as Albany pursues rent reform, we have an opportunity to prepare for the next generation of housing policies.

First and foremost, New York City needs to expand the NYC Rent Freeze Program. Specifically, the Senior Citizen Rent Increase Exemption (SCRIE) and the Disabled Rent Increase Exemption (DRIE) freeze rent for qualifying individuals who live in rent-regulated units. The policy provides an important safety net for the most vulnerable New Yorkers, but the city needs to better disseminate information about the programas well as expand the pool of who is eligible. Specifically, DRIE should be augmented to cover households that are responsible for looking after an immediate member of the family with a disability. And both SCRIE and DRIE should be available to qualifying individuals and families struggling to make ends meet in market-rate housing.

Second, rent-stabilized homes need to be means tested. New Yorkers who live in rent-stabilized units typically stay for well over a decade, regardless of any change in socioeconomic status or size of family. Indeed, New York City’s churn rate – households that have moved in the past three years – is the lowest of any city in the country. These affordable units need to be consistently allocated to New York families struggling to make ends meet in market-rate rental apartments.

Third, the city and state need to fully fund and implement the Home Stability Support Program, a voucher-based system for qualified homeless individuals and families. The cost of the system will be offset by the reduced burden to the city’s shelter system. To be sure, as the city saw with the severe rise in homelessness after the demise of the Advantage Program in 2011, the only way to combat homelessness is to consistently fund programsthat provide families with material housing and rental support.

Our ideas are just the start for charting a better path for New Yorkers trying to thrive in our city. As Albany tackles rent regulations, we hope we can forge a better regulatory and legal framework.

Jay Martin is executive director of the Community Housing Improvement Program (CHIP).

One thought on “Opinion: Tightening Rent Regs Won’t Ease the Housing Crisis, But These Steps Would”

How bout getting rid of rent stab and just giving vouchers to qualified truly needy people? That way people are not tied to an apt if their employment or other situations change.

Admittedly a tough sell politically, and if not possible, I agree means-testing would be a big step forward. But i’m not sure that would be that much easier politically either.