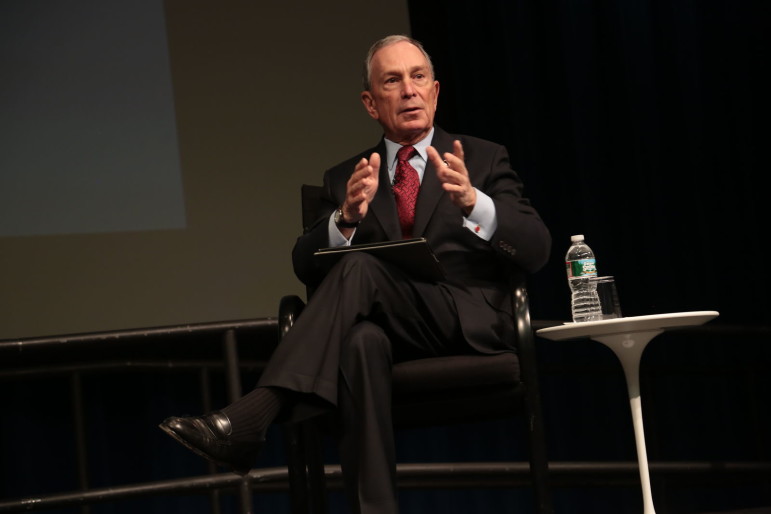

Ed Reed/City Hall

Mayor Bloomberg was wrong to overturn term limits for short-term political advantage. But they might not be what New York City needs for a healthy democracy over the long term.

In any democratic system, the ultimate check on governmental power must come from the people themselves. That capacity is determined by the electoral process. There are two basic problems that characterize our existing electoral process: too few voters and too many dollars.

Since 1965, when John Lindsay ran for election, the number of people voting for mayor has declined from 2,652,454 to 1,166,313 in 2017. The downward slope was interrupted only twice over that time: in 1989, when the city charter was under consideration (and an extraordinary high turnout in African-American districts elected David Dinkins); and in 2001, right after the 9/11 attack on the World Trade Center (electing Michael Bloomberg).

In 1989, when the Campaign Finance Board first started keeping records, the total amount of money spent by all candidates for mayor was of $24,064,270. Until very recently, spending rose consistently. Michael Bloomberg kept breaking his own incredible records, peaking in 2009 by spending $108,371,688 of mostly his own money. A total of $59,694,044 was spent by all candidates in 2013; but it dropped to $20,608,773 in 2017 when Bill de Blasio ran with little opposition.

Compared to the institutional issues we have addressed so far, the municipal government is more limited in what it can do through the charter to make the electoral process more fair and open because most election law is written in Albany. Up until very recently, the governor and the legislature have demonstrated little interest in meaningful reform. Then, as the state budget process came to a close at the beginning of this month, there appeared a modest sign of hope when Albany leaders appointed a commission to develop a plan for the public financing of elections. The commission has until November to develop it, at which time the legislature can either let the plan go forward or overrule it. We shall see.

The panel, yet to be chosen, was also charged with examining the efficacy of fusion voting, which allows candidates to run on multiple party lines. Fusion has been instrumental in electing three very consequential mayors (Fiorello La Guardia, John Lindsay and Rudolph Giuliani) and, especially recently through the Working Families Party empowering progressives—much to the chagrin of the governor and the state Democratic party, which has passed a resolution calling for the end of fusion voting. It is telling that even when Albany makes a modest gesture toward reform with the appointment of a board to consider public financing, it colors that act with the prospect of diminishing voter choice.

That said, there are things that New York City can do on its own, if the present charter commission so chooses. The city already has one of the best campaign finance systems in the nation. At least, it works well unless billionaire candidates decide to fund themselves and choose not to be governed by its terms. Federal law, another huge obstacle to election reform, prohibits us from making participation in public financing compulsory.

Yet, there are tools the city can use. All three propositions put forward in 2018 by the commission Mayor Bill de Blasio appointed were designed to address issues of citizen involvement. All three passed by large margins, attesting to voters’ receptivity to reform—or perhaps their total disgust with what now exits. There are still important issues that we can address through the charter—one of which the charter revision commission is likely to overlook, the other which it has been widely encouraged to take up.

The record shows that term limits have been strongly embraced in the city as a way to undo entrenchment and promote change, especially when it involves the three citywide offices, borough presidents and council members. Term limits of two consecutive 4-year terms have been approved overwhelmingly for these principal offices in three separate referenda (by 59 percent in 1993, 54 percent in 2006, and 74 percent in 2010). For this reason, their perpetuation is not likely to be challenged by the present charter commission. That is regrettable.

Mayor Michael Bloomberg and the City Council transformed the idea from a vehicle for reform to a matter of principle in 2008 when they decided to undo the existing term limit law through local legislation without giving the public an opportunity to vote on it so that Bloomberg and the other affected officials could seek a third term. When the charter commission for which I served as research director in 2010 decided to put the issue back on the ballot, I agreed with the decision because I believed that the council and the mayor should not have overruled the (twice expressed) will of the people to advance their own personal careers — that the issue should be determined by popular vote. I still do. But like then, I have strong reservations about term limits as a practice.

Yes, term limits serve as an antidote to entrenched leadership and tired incumbency. Social science research, however, apprises us of other effects that may undermine meaningful reform. At minimum, they deny voters an option to elect a favored official beyond the defined limit. They have also been shown to make elected officials more focused on running than serving; which can result in more attention to fund-raising — if not for reelection to their present positions, then to build a campaign chest for the next. Politicians who are term-limited have fewer incentives to be invested in the office they hold. They become, for all practical purposes, perpetual candidates, yet out of reach to the voters in their final term.

The lack of seniority that is occasioned by constant turnover has also been found to have a negative effect on the governing process. Elected officials, especially those in legislative branches, have less time to develop independent expertise on policy issues that is typically gained through tenure on specialized committees. As a result, they can become more dependent on lobbyists for information, which exacerbates the toxic fundraising cycle. Given these concerns, a limit of three terms rather than the present two for major offices might allow us to benefit from the advantages of this popular reform while being less susceptible to its drawbacks.

Meanwhile, a voting reform that has gotten a lot of attention by the sitting charter panel is Instant Runoff Voting (IRV). For that reason, I feel compelled to express some cautionary notes. IRV is currently practiced in 15 cities and the state of Maine. The main objective of IRV is to eliminate the cost of a runoff election. Instead of choosing one favored candidate, IRV has voters rank order candidates by preference. If no candidate gets a required minimum vote (say 40 percent), technology automatically eliminates the low scoring candidates, sorts the remaining preferences, and names the winner based on the scattered information initially fed to a computer by the voters. It is like having Siri choose your mayor or council member.

IRV has also been found to be confusing. Not every voter has a list of multiple candidates they find acceptable. Many people who go to the polls are not so well informed about all candidates running. Researchers have discovered incidences of disqualifying errors made at the polls, under-voting and over-voting. They have observed higher “information costs” assumed at the ballot box by voters seeking to make intelligent choices. These costs have been found to have a disparate impact, falling more heavily on districts composed of less educated, racial minority, immigrant, elderly, and lower-income populations. There is some evidence that IRV discourages voting and lowers turnout.

Taken together, the unexamined perpetuation of term limits and the introduction of IRV could have the net effect of increasing the role of money in politics and undermining the influence of individual voters. Given how unreliable the more powerful state government has been as a partner for election reform, this city charter commission needs to adopt measures that move us in the opposite directions.

Joseph P. Viteritti is the Thomas Hunter Professor of Public Policy at Hunter College and most recently author of The Pragmatist: Bill de Blasio’s Quest to Save the Soul of New York (Oxford).

One thought on “Opinion: Is the Charter Revision Commission Looking at the Wrong Election Reforms?”

When Mayor Rudolph W. Giuliani appointed a commission to study the possibility of revising the City Charter in June, he seemed to have one main goal: keeping Mark Green, the Public Advocate, from automatically succeeding him if he is elected to the Senate next year.