City Limits

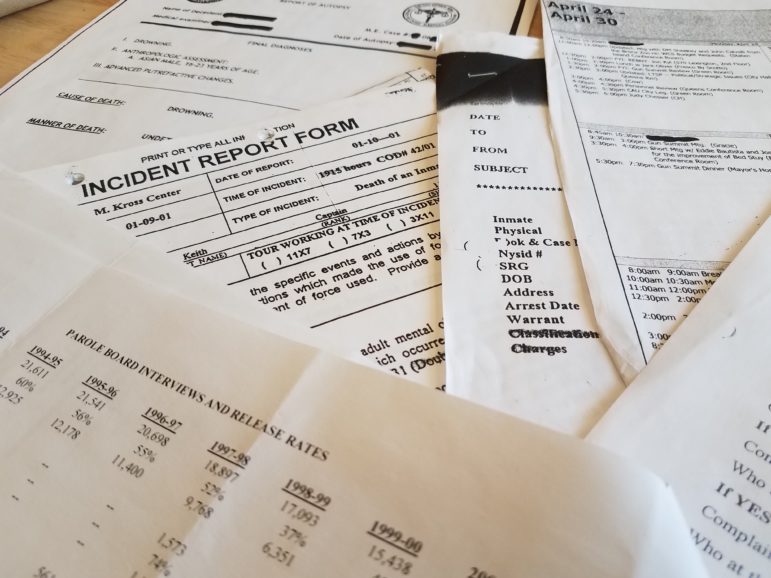

Information released under FOIL about parole release rates, an inmate’s murder, an autopsy that found ‘undetermined’ intent. a mayoral aide’s schedule and a ‘see something, say something’ tip line.

Official documents that seem to disappear. Requests for public information that are never approved or denied. Months and months of delay in receiving basic information. Getting access to government papers only when a minder is present, and where photographs and copies are not allowed.

Those are some of the war stories that journalists and private residents told City Limits when we surveyed readers and reporters about how well the state’s Freedom of Information Law is performing.

The law dates to 1978 and treats all records created or kept by government as accessible by the public unless they fall under one of several exemptions, like documents whose release would interfere with a law-enforcement investigation or reveal the questions on a civil-service test. It covers “all units of state and local government in New York State, including state agencies, public corporations and authorities,” according to the Committee on Open Government, an entity that monitors and supports compliance with the law.

For more than four decades, the law has served as a fundamental tool for reporters, advocates and others who want to see what government is up to. The Freedom of Information Law, or FOIL as it’s known, let The New York Times uncover details about September 11, allowed NY1 to document problems in homeless shelters and helped WNYC cover illegal hotels. Smaller news outlets have also used the law to the public’s benefit, whether it was the Village Voice documenting crimes by 1990s mayoral aides, the Norwood News getting crime statistics broken down by patrol sector or City Limits chronicling the income disparities in affordable housing lotteries.

While a vital tool, FOIL has also long been a source of frustration for reporters, advocates and others. Back in 1997, Manhattan Borough President Ruth Messinger filed a freedom of information lawsuit against Mayor Rudolph Giuliani charging he had illegal withheld information—about how many FOIL requests the city had received and denied during his term.

In recent years, even as there have been some improvements in access to local data and tracking FOIL requests, the city’s policies on police disciplinary files, “agents of the city” communication, mayoral emails and even records-office staffing have come under scrutiny.

That’s why a group of journalists, press organizations and advocates has written to Speaker Corey Johnson asking the City Council to assess the FOIL system and consider improvements. (Read that letter here.)

“Transparency in government and accountability in our elected officials is the foundation of our democracy, and journalism is the key to updating the general public on what occurs in City Hall. The Council has and always will support a free press, and we will continue to encourage our colleagues in government to improve the Freedom of Information Law process,” said Breeana Mulligan, a spokesperson for the New York City Council, in response to the letter.

Delays and denials

Our survey generated a modest 16 responses, but they reflected the breadth of topics that have been the subject of FOIL requests – and a variety of complaints about how the city responded.

“Over the years, I have been forced to repeatedly FOIL the NYPD for additional information about the redesign of Rodman’s Neck. I FOILed originally in the 2014/2015 timespan to find out where funds dedicated towards relocating the range were redirected to which I never received an adequate response,” wrote John Doyle of City Island Rising, Inc. “In 2018 I FOILed to get information about other police departments who use the range as well as environmental reports about possible lead poisoning and I received page a totally inadequate one page response.”

Micah Morrison, a journalist with Judicial Watch, also had a complaint about the police. “The NYPD denied my FOIL requests for information related to the 1974 murder of NYPD Patrolman Phillip Cardillo inside a Harlem mosque—the so-called ‘Harlem Mosque Incident.’ In 2017, we sued the NYPD for records related to the case,” Morrison wrote. “The NYPD claimed that, more than 40 years later, the case was still ‘active and ongoing.’ The judge accepted the NYPD’s argument. We lost the case. We are appealing.”

But it’s not just the NYPD. The New York Post has complained about delays in the FOIL office of the Department of Education. Other agencies also have their issues, apparently. One reporter told our survey: “I FOILed contract information for a specific Brooklyn shelter from the Department of Homeless Services in July 2017 and have yet to receive the information.” Another said he’d had trouble getting information out of the lowest level of local government. “Last November, I made a series of requests to the local community board for documents related to board business as well as expenditures over the last three completed fiscal years,” wrote one reporter. “It has now been more than 100 days, and I have yet to receive those financials.”

Separately, that same reporter said he’d asked to see “a multi-million-dollar agreement for a company to run a transitional homeless facility in our coverage area.”

“In order to look at the document, I had to travel out of the Bronx to the World Trade Center in Manhattan, go through security, and then have someone sit with me while I looked through the document,” the reporter wrote. “[I was] not allowed to make any copies or take any pictures.”

One reporter noted that agencies are uneven in how they address FOIL, with some providing decent compliance: “NYC Housing Development Corporation… is a very responsible agency regarding FOIL in my experience. Empire State Development … is somewhat responsive but often quite slow,” he wrote, and added: “Multiple requests to the NYC Department of Buildings went into the ether, never officially denied.” (Empire State Development is a state agency; while our survey focused on city government, some people who responded said they’d had more trouble with state entities.)

Some reporters’ complaints venture into the tricky territory of trying to prove whether a document exists or not. “In one recent story, claims of abuse by a resident against a government employee had been documented [in] reports filed by a former department supervisor,” wrote one journalist. “When I asked for those I was told that they had all disappeared. I’ve found that documents I knew had existed suddenly disappear or can’t be found or don’t exist when I FOIL.”

One survey respondent who claimed to work for a local agency said there are legal conflicts that make it hard for public servants to comply with FOIL.

“FOIL was written at a time when privacy wasn’t a hot issue. FOIL needs to be revisited and amended to work with privacy laws or at least clarify how privacy laws and FOIL should work together or be applied,” the person wrote. “Government agencies do not have enough clear guidance on how to protect the public with regard to guarding their information while also making government records accessible.”

Teeth for truth?

Many of the people who responded to our survey endorsed solutions like strengthening the FOIL statute, adding resources to agencies’ FOIL offices or a change in policy at City Hall or at the agency level to orient city departments toward broader, more timely disclosure.

But others had ideas of their own. There was a call for annual reporting by agencies on FOIL compliance, and a plea for the city to hire people for FOIL posts who are passionate about getting information out. At least one person saw a need to update FOIL for the digital age and the privacy concerns that are now so common.

Much of the feedback focused on putting teeth in the FOIL law.

“The laws in New York State are too weak. Connecticut and New Jersey have an independent body with legal authority to force compliance after they render their binding advisory opinions,” wrote one participant.

“There should be a time-frame by which if an agency cannot find the records, the matter is elevated to the Public Advocate or Inspector General’s Office. If at that point, no records are found, a response should also be required to the Mayor’s Office,” wrote another.

“There needs to be a real appeal process, to allow for actual review (outside of the courts) for compliance, or to compel an agency to comply,” wrote a third.

2 thoughts on “Delays, Denials, Documents That Disappear?: Survey Reveals Range of Concerns About FOIL in NYC”

I am a Darkskin Male Black that was arrested July 26,1995, Tried 3 Times,Convicted in New York county for a Description of a Male White Perpetrator that allegedly did a Robbery without a weapon,2 Detectives in the 9th Precinct during my Interrogationadmitted that they know I didnt do the Crime on Videotape, 7th Judge Patricia Anne Williams who is Female Black had been Recused from my Criminal Case because she was fair, without Notice in Docket #7214/95.Arresting Police Officer Thomas Lilly and the ADA Christopher Lilly is & was Brothers on my same Criminal Case. I been trying to FOIL this Videotape prior & always Claimed I am Innocent but NYPD FOIL still trying to cover up Black Lives Matter

I am giving you Authorization to Publish my Criminal Case Docket #7214/95 without you or your Company receiving Royalty’s Fees when Publishing my Case or Story at this time.