Macmillan

FLASH: THE MAKING OF WEEGEE THE FAMOUS

By Christopher Bonanos

Henry Holt and Co.

June 2018

400 Pages

Perhaps you have heard about The Herald Tribune, The Brooklyn Eagle, The New York Telegram, The Evening World, The Journal Tribune. There were several others, but today they are mostly all dead. Many of the papers died because they lost their readers. They were boring. No pictures.

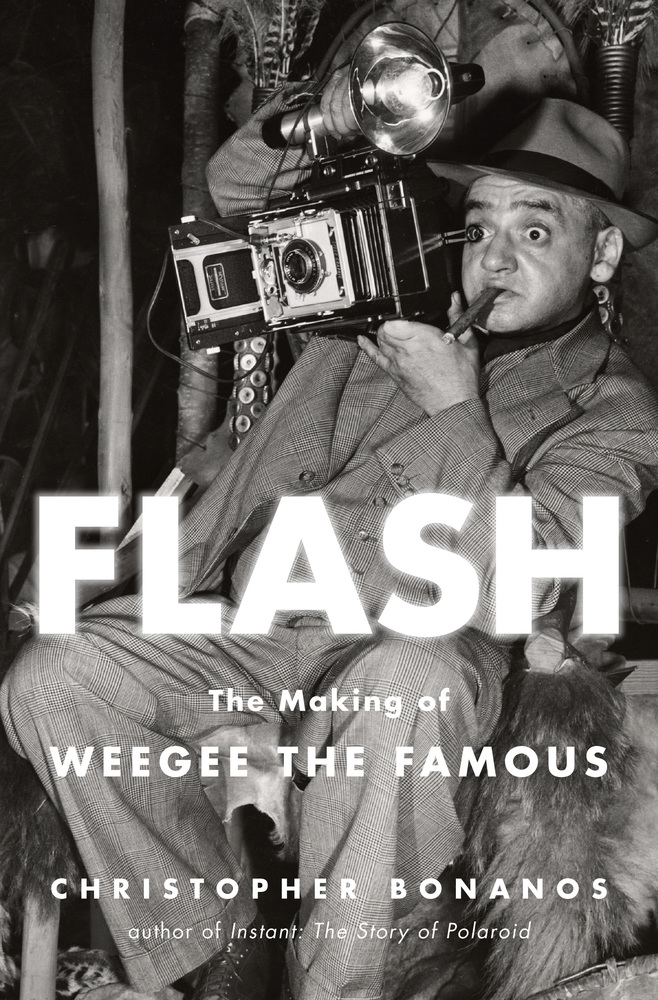

That’s until Usher Fettig arrived from eastern Europe, changed Usher to Arthur. Described as a young man as shy, awkward, then as broke, unpolished at 14—a seventh grade dropout, soon described as funny, smart and ambitious. In 1925 he started to reinvent himself, changed his name to Arthur Weegee. Soon this evolved into “Weegee the Famous,” introducing himself in conversation or on talk shows as the “world’s greatest living photographer.”

To earn that title, he lived by night, teaching himself to deal with a tough town. He knew that the “interesting” people were gangsters and movie stars. His job was to find these people and photograph them, then sell these pictures to newspapers, magazines. The typical Weegee subject was the corpse of a criminal, preferably a gang member, with a number of bullets in him, lying face down on the sidewalk, blood running into the gutter.

He did not have a regular “job” that tied him to one publication and he became increasingly interested in photographing naked women, which brought him into the dressing rooms at Broadway shows. When he wanted to hang out with the journalism stars – like A.J. Liebling, and Joseph Mitchell – he had connections at the New Yorker.

As Christopher Bonanos’ biography tells us, he spent the rest of his life mastering more of the media. Some of his pictures were not classics, some unforgettable—like Gladys MacKnight and Donald Wightman, New Jersey teenagers who offered no smiles; they had just murdered her mother with an ax. Hungry to conquer more territory, Weegee in later life visits a short list of great American cities: Philadelphia, New Orleans, and Hollywood, where he was among the stars, where he belonged.

Those long-dead newspapers, they were “the media.” Today media may refer to a creative relationship among a great variety of art forms: newspapers, radio, TV, film, books, websites Twitter. Today they are the way we speak to one another. Two generations ago we might rely heavily on the Times or Washington Post to educate us on the quality of our lives or our political candidates. Not anymore.

Why should we want to learn about Weegee today? First, as a result of his work, the appearance of New York City probably improved. Second, a glorifier of violence, he’s a shameful part of New York City history, but a part we should know. Third, blood still runs in the gutters and we should do something about it.

Raymond A. Schroth, S.J., author of nine books, is an editor emeritus of America magazine.