Jarrett Murphy

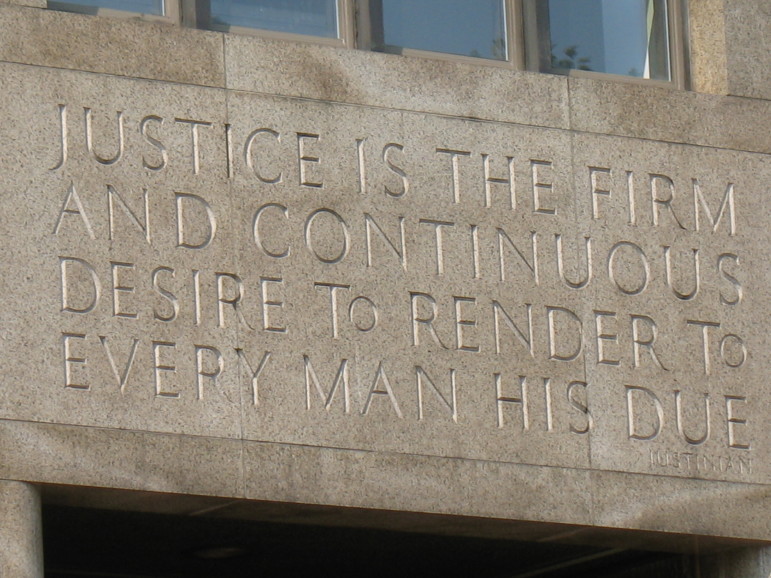

The facade of the criminal court building in Manhattan.

Last year, Ms. C – a 30-year-old single mother – was arrested after she was accused of damaging another car’s side-view mirror. This was her first and only run-in with the law, and she maintained her innocence.

The prosecutor on the case consented to an Adjournment in Contemplation of Dismissal (ACD), which is a mechanism commonly used in our criminal legal system to dismiss and seal all charges, usually after six months or one year of “good behavior.” According to an analysis of the more than 43,000 Legal Aid Society cases that were ACD’d after being opened between January 1, 2016 and December 31, some 99.4 percent of cases in which an ACD is ordered result in dismissal.

But during the period between the ACD and the dismissal, the charges appear as a pending case and are accessible to the public – including employers.

Shortly after the ACD was issued in Ms. C’s case, her employer of three years caught wind and terminated her position as a healthcare worker.

Ms. C then frantically tried to apply for similar jobs but was repeatedly rejected because of the open ACD. She was only able to find new employment after the case was finally dismissed and sealed. But the damage had already been done.

During the months between the ACD and the dismissal, Ms. C was forced to rely on food stamps and the financial support of her mother, a nurse aide, in order to feed and house her three children.

Even though an ACD is not a conviction or a plea agreement, and does not involve any admission of guilt, Ms. C was continually discriminated against by employers. Her life was completely upended.

Ms. C’s case isn’t an outlier. Thousands of New Yorkers have experienced similar nightmarish scenarios and many across the state are suffering this treatment right now as a result of an open ACD.

In 2017, almost 80,000 cases in New York State were dismissed after an ACD. This represented nearly one-fifth of all case dispositions that year.

Current law already protects workers after their ACD’d case is dismissed, but during the time between the ACD order and the final dismissal, workers are subjected to rampant discrimination that prevents them from maintaining employment and supporting their families.

This puts people who have never been convicted of a crime in a worse position than people with convictions, merely because of a gap in the law that does not protect people with “open” cases. Such an unfair disparity is clearly an oversight that must be fixed and, at long last, Albany has a real opportunity to do this.

Governor Andrew Cuomo introduced a proposal in his executive budget, and State Senator Jose Serrano and Assembly Member David Weprin introduced proposals (S3995/A6045), that would correct this injustice.

For cases that result in ACDs, these bills would prohibit employers from using the arrest or prosecution as a basis for denying employment or firing the worker, and they would require employers to lift any suspension imposed because of the arrest or prosecution. Furthermore, the changes would prevent employers from seeking information about an arrest that resulted in an ACD.

With the landscape change in Albany and renewed appetite to reform New York’s unfair and discriminatory criminal legal system, this issue and others stand a genuine chance of reform. We urge Albany to prioritize the immediate passage of this needed legislation.

Melissa S. Ader is a staff attorney in the Worker Justice Project of The Legal Aid Society.

Note: In the analysis of Legal Aid cases from 2016, the overwhelming majority of the 0.6vpercent of cases that did not end with an ACD instead resulted in a non-criminal violation, such as disorderly conduct. State law already protect workers whose criminal case results in a non-criminal violation.

Get the best of City Limits news in your inbox.

Select any of our free weekly newsletters and stay informed on the latest policy-focused, independent news.

One thought on “Opinion: Loophole Means Criminal Charges Set to be Dismissed Still Upend Lives in NYS”

Pingback: Qualities to Look for in a Competent Personal Injury Lawyer | Attorney at Law Magazine