Osaretin

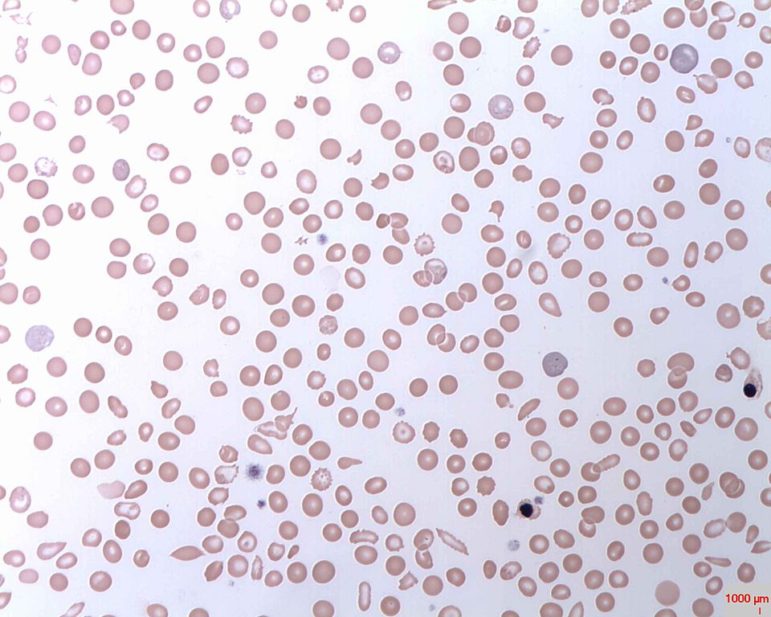

Sickle cell disease is an inherited disorder that prevents red blood cells from carrying oxygen throughout the body properly, due to their crescent-like, sickle shape.

Chronic pain, health complications and frequent trips to the emergency room are everyday concerns for an estimated 10,000 New Yorkers living with sickle-cell disease.

Together, these individuals account for 10 percent of the country’s population diagnosed with the inherited blood disorder.

Despite this geographic concentration, patients, advocates and health providers say that funding and overall quality of care continues to fall short in New York state.

In 2017, the state allocated $250,000 to sickle-cell in its annual budget. Legislation to boost that funding has been introduced in both the New York State Assembly and Senate, asking for a budget of $3 million.

The funding would establish eight demonstration programs and one coordinating center for sickle-cell disease education and treatment throughout the state.

Proponents of the bills say this new infrastructure would encourage sickle-cell disease patients to get preventative care, as well as improve the treatment they receive in emergency rooms and hospitals.

The legislation has yet to pass, and was not reflected in Governor Cuomo’s 2019 Executive Budget announced on Jan. 15.The bill was reintroduced for the 2019 to 2020 legislative session.

Thomas Moulton, a pediatric hematologist and oncologist in New York City, says it’s a travesty that the state has consistently decreased funding.

“When I started out in the late 90s and early 2000s, there wasn’t much [in the budget], but it was still $500,000 for sickle-cell disease,” Moulton says. “And costs have only gone up.”

A painful disorder

Sickle-cell disease is an inherited disorder that prevents red blood cells from carrying oxygen throughout the body properly, due to their crescent-like, sickle shape. When these misshapen cells travel through the blood vessels, they get stuck and clog blood flow.

This can cause severe pain and lead to other health complications, such as infections, acute chest syndrome and stroke. Adolescents and adults with sickle-cell may suffer from chronic pain, as well as severe episodes, called pain crises.

The life-long disorder varies in severity from patient to patient, with an average life expectancy of 42 years for women and 38 for men.

Get the best of City Limits news in your inbox.

Select any of our free weekly newsletters and stay informed on the latest policy-focused, independent news.

Currently, sickle-cell is the most expensive disease to New York State Medicaid. The state spends $15,000 per patient each year, almost 50 percent more than that of HIV care.

While the amount of people in New York newly diagnosed with HIV has decreased 37 percent from 2009 to 2016 and deaths due to HIV/AIDS have fallen to historic lows, mortality rates of sickle-cell disease have steadily increased since 1979.

Advocates feel that the state turns a blind eye to the specific needs of sickle-cell patients, even as it channels $200 million to combat HIV, a disease that already is targeted by $2.5 billion in statewide funding.

Sickle-cell advocates merely hope that ailment also receives adequate funding.

“We appreciate that we’re attacking those other illnesses, but we want [sickle-cell] seen as the major blight that it is,” says James Sanders Jr., senator for New York’s 10th District and the primary sponsor of the bill to increase funding.

Sanders believes the program will pay for itself, mitigating emergency room visits through an established network of preventative care. As a result, New York State Medicaid could save between $4 and $5 million.

“You can pay a small price upfront or continue to pay the staggering sum on the backend,” Sanders says.

In comparison to other inherited diseases such as cystic fibrosis, sickle-cell is advocated for on a much smaller scale and historically underfunded. In 2011, national funding for cystic fibrosis research was $254 million, almost four times the $66 million allocated to sickle-cell.

Cystic fibrosis, which primarily affects Caucasian populations, has approximately 30,000 patients in the United States—less than one third of sickle-cell patients nationwide.

Illness and inequality

In New York, 89 percent of babies born with sickle-cell disease were of African American descent, according to data from the Center for Disease Control and Prevention.

Because the disease disproportionately impacts communities of color, race is another factor that impacts patients’ quality of care.

Deborah Pannell says her husband Ivor, who died from sickle-cell disease at age 45 in Oct. 2009, faced racial discrimination when filling prescriptions for pain medication.

“There was one day [when we lived in Astoria], Ivor went to no fewer than 20 pharmacies, and none of them would fill his prescription,” Pannell says. “Then, I, with my white face, walked into the pharmacy with the same prescription and they filled it.”

During this time period, the couple was on Medicaid, which Pannell says added another obstacle to the process.

“There were ways that I could advocate on his behalf that were really helpful,” Pannell says. “But I was aware that it was because I was a white woman, and I could take advantage of that privilege.”

With roughly 50 percent of the sickle-cell population relying on Medicaid, adult patients can have a hard time securing healthcare specialists to monitor their treatment effectively.

Lamia Barakat, director of Psychosocial Services at the Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia and Professor of Clinical Psychology, says that adult populations have more limited access to comprehensive sickle-cell care, as few providers will accept new patients with Medicaid.

“Unfortunately, this disparity is reflected in high rates of morbidity and mortality among young adults as they transition from pediatric to adult care,” Barakat says.

Insurance woes and treatment failures

Insurance status also impacts the quality of care children with sickle-cell disease receive.

A 2014 study published in the Journal of Pediatric Hematology/Oncology found that type of insurance provider impacts how effectively families of children with sickle-cell disease can access care to manage health complications.

“In our study, we noted that children with public insurance were more likely to rely on urgent health care with delays in care critical to effective treatment,” Barakat says.

Barakat says that public insurance is a proxy for other barriers to care, such as living in poverty, low health literacy and decreased access to programs that support the healthy development of children.

“Of course, the converse is true,” Barakat says. “Primary private insurance is a proxy for facilitators of access to consistent, high quality preventive and interventional care inside and outside of acute care settings.”

Cheryl Cannon, who lost her 34-year-old son, Shakir, due to acute lung complications due to sickle-cell disease in Dec. 2017, experienced insurance challenges, despite having a private provider.

“My insurance company refused to pay for blood transfusions initially,” Cannon says. “I had to pay $10,000 out of pocket until I straightened it out that my son had a life-threatening illness.”

Cannon acknowledged that her family was fortunate, as Shakir’s blood transfusions, which he received once every three weeks throughout his entire life, were eventually covered by insurance.

With limited access to specialized providers, many sickle-cell patients depend on emergency departments for their care. Here, patients face long wait times, regardless of higher pain and triage acuity levels.

On average, sickle-cell patients wait 25 percent longer than the general patient sample and 50 percent longer than patients with long bone fractures.

In the midst of a pain crisis, sickle-cell patients display no physical symptoms despite being in severe distress.

“The pain is excruciating,” Ada Gonzalez, a 54-year-old sickle-cell patient says. “You could be fine one minute and within five minutes, you’re calling the ambulance.”

Pannell says throughout her time in emergency rooms with Ivor, she witnessed different responses among patients with the same disorder.

“You hear some of them howling and screaming and shrieking in pain,” Pannell says, explaining that others remained quiet while awaiting treatment despite being in great discomfort.

“If you misbehave, you’re labeled as a troubled patient,” Pannell says. “And if you behave well, [doctors and nurses] might mistake you for not being in pain.”

Tartania Brown, a palliative care physician and patient living with sickle-cell disease herself, described this challenge in a written testimony to Governor Cuomo, offering her support for the Senate and Assembly bills.

“We face regular bias as patients where nurses, hospital staff, and physicians are often misinformed and assume we are all drug addicts,” Brown wrote in her statement. “Far too often, we are misdiagnosed and ill-treated.”

Although there has long been an underlying stigma around sickle-cell, the ongoing opioid epidemic is exacerbating a hesitation to believe patients’ reported pain and administer appropriate medications, Moulton says.

“Somebody with a chronic illness like diabetes goes in [the emergency room] and said, ‘I take this much insulin and these are my medications,’ and they’re labeled a good patient,” Moulton says. “But a patient with chronic pain like sickle-cell said ‘this is what works and what doesn’t work’ and they’re labeled as drug addicts.”

As a result, sickle-cell patients may not receive pain medication in a timely fashion at the emergency room.

“Even when they advocate for appropriate care and provide information on their typical treatment protocol, they are started at a type and level of pain medications that is insufficient,” Barakat says.

Cannon revealed that throughout Shakir’s adult life, he too faced this negative stereotype when seeking treatment. Sometimes this made him hesitant to go to the hospital in the first place.

“He admitted to me that one of the reasons why he put off going was because the staff and doctors who don’t know about the disease feel these people are drug seekers,” Cannon says. “To date, that is still a problem.”

This is why, Cannon says, many patients wait until the very last minute when in pain crises, putting their health at risk.

“As a physician, I have heard the training during medical school that has plagued the perception of our pain and treatment,” Brown says. “[As a patient], I find it increasingly challenging to find doctors in New York who know enough about my disease to provide comprehensive care.”

New hope, but funding needed

In Aug. 2018, Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai Hospital received a $4 million grant from the National Institute of Health to research new approaches for treating sickle-cell.

Dr. Jeffrey Glassberg, Associate Professor of Emergency Medicine and head of the research team, said in the press release announcing the grant that “alternative treatments will improve patient care, reduce ED visits, and lower healthcare expenditures.”

With an increase in research and clinical trials for the disease, advocates remain optimistic that statewide funding will follow suit.

“I hope within five years, we can get the bills passed,” Cannon says. “So people who have the disease can really go and get the treatment they need.”

One thought on “NY Support Lags for Sickle-Cell Patients Facing Pain, Poor Treatment, Discrimination”

bless this vital effort. thanku deeply for all u do. the suffering of the few patients i witnessed was indescribable torture.

love oht