Murphy

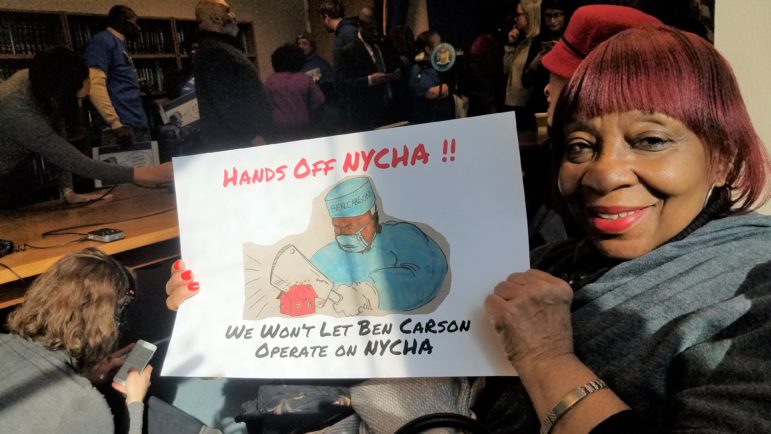

Audrey Clemmons from the Drew Hamilton Houses expresses her concerns about a HUD takeover at a press conference before the monitor deal was announced,

A cheer went up Thursday morning in a packed conference room overlooking City Hall when NYCHA tenants, elected officials and advocates learned that the U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development was not going to put the nation’s oldest and largest public-housing authority into receivership, agreeing instead with the city to install a monitor over the troubled system.

A cautionary tone soon emerged, however. “We cannot relax,” Judith Goldiner, an attorney with the Legal Aid Society, said at the press conference convened by Community Voices Heard, an advocacy group with many NYCHA tenants among its members. “We don’t know what this federal monitor is going to do.”

More details emerged about an hour later and three blocks away when HUD Secretary Ben Carson and Mayor de Blasio announced their deal. According to the agreement, the city maintains a measure of control over the system. The monitor will not oversee day-to-day operations at NYCHA, but will have sweeping powers.

The monitor, who has yet to be appointed, and the city will hire an outside consultant “to examine NYCHA’s systems, policies, procedures, and management and personnel structures, and make recommendations to the city, NYCHA, and the monitor to improve the areas examined.”

Then, the monitor and NYCHA are supposed to create a plan “setting forth changes to NYCHA’s management, organizational, and workforce structure (including work rules), and overarching policies”—language that indicates the possible abrogation of union contracts. If NYCHA and the monitor disagree on the plan, HUD and the U.S. Attorney get to decide which plan to use. Once a plan is adopted, it becomes NYCHA’s official policy.

HUD and the U.S. Attorney for the Southern District of New York also gain meaningful control over the system. The city has to get both entities approval of all candidates to become the permanent chairperson and chief executive officer for NYCHA.

Get the best of City Limits news in your inbox.

Select any of our free weekly newsletters and stay informed on the latest policy-focused, independent news.

The agreement foresees the possibility that HUD, the monitor and their chosen NYCHA CEO could exempt parts of the authority from contracts and local or state laws.

It notes Carson’s authority to, with the monitor and CEO’s concurrence, take control of part of the authority ” in order to “abrogate[e] any contract to which the United States or an agency of the United States is not a party that … substantially impedes correction of the substantial default” or to tell NYCHA “not to comply with any State or local law relating to civil service requirements, employee rights (except civil rights), procurement, or financial or administrative controls that … substantially impedes correction of the substantial default.”

The agreement overlaps in several areas with the consent decree the city signed with federal prosecutors last spring. The level of city spending required—$2.2 billion for specific actions related to lead, mold and pests over 10 years, on top of a baseline $970 million in operational funding and $2 billion in capital spending over a decade—is identical.

The federal government, whose underfunding of public housing contributed mightily to the crisis at NYCHA, does not commit to any additional funding.

On the key question of community engagement, Thursday’s agreement goes further than the June deal did. It requires the monitor to “engage with NYCHA stakeholders, including residents and resident groups,” convene a Community Advisory Committee (“consisting of NYCHA stakeholders such as NYCHA’s Resident Advisory Board; resident, community, and employee representatives; senior NYCHA managers”) at least four times a year to “solicit input regarding the achievement of the agreement’s purpose.” The monitor is also supposed to devise ways to solicit comments from residents and others.

But the fact that the deal itself was crafted without apparent tenant input bothered Alicka Ampry-Samuels, a Brooklyn City Councilmember and the public-housing committee chairwoman, who grew up in a NYCHA development. “Were the residents at the table?” Ampry-Samuels, one of a dozen elected officials who crammed around the podium at the press conference. “That should have been part of the settlement.”

To a person, the officials and tenants who spoke opposed the idea of a receiver, largely because of the Trump administration’s antipathy to public housing. A monitor was seen as preferable, if not perfect.

Some of Ampry-Samuels’ colleagues at the microphone did not shy from blaming the city for its role in fomenting the NYCHA emergency.

“At the city level we have seen the stories of neglect of obligations to address lead conditions, to address mold, to provide proper security. A lot of these things are principally about funding but they are also about proper management of this system,” said Sen. Brian Kavanagh, chair of the Senate housing committee. “We are not unaware that the management of this system has been deficient.”

But the focus was on the role of federal funding in the story. “They have destroyed us,” said Agnes Rivera, a Wagner Houses resident (whom City Limits interviewed for our investigation of NYCHA’s fiscal crisis a decade ago). “They have starved our housing.”

“The question is, how did we get to this point?” asked Rep. Nydia Velazquez. She noted that, in addition to the federal pullback, the Giuliani and Bloomberg administrations reduced city contributions to NYCHA, too. So did the state, early in this century.

Kavanagh noted that the state had recently begun making bigger commitments, although much of that money had not yet flowed to the authority. And Goldiner said it was “disgusting” that Governor Cuomo had not allocated new money for NYCHA in his fiscal 2020 budget.