Official White House Photo by Shealah Craighead

Rolling back regulation on businesses has been a hallmark of President Donald Trump, seen here as he prepares to cut the ‘red tape’ of regulations on December 14, 2017.

Worker deaths have risen in New York State over the past two years. But federal inspections by President Trump’s Occupational Safety and Health Administration are fining New York workplaces less. According to its own statistics on federal inspections in the state, the agency is performing slightly more inspections, but finding fewer infractions per visit, issuing fewer violations overall, and, accounting for inflation, issuing smaller penalties.

“I think what you see is OSHA doing less complicated inspections,” said Deborah Berkowitz, worker safety and health program director for the National Employment Law Project, who also worked as a senior policy advisor for OSHA under President Obama until 2015.

Nationwide OSHA Changes Under Trump

At the advent of the Trump Administration, labor leaders and health & safety advocates had little hope for the Department of Labor and its OSHA division to increase or even maintain protections for workers. Indeed, many career OSHA employees headed for the door just as Donald Trump was clearing his throat to take the oath of office as the nation’s 45th President.

“I left at noon on January 20, 2017,” said Jordan Barab, who worked as Obama’s Deputy Assistant Secretary for OSHA.

Overall, OSHA appears to have been successful at its mission. Since the creation of the agency in 1971, deaths and injuries in the workplace have declined by 65 percent, even with a workforce twice the size as it was then.

Under Trump, official policy changes did not come to OSHA as furiously as they did within another Nixon-era creation, the Environmental Protection Agency. Unlike the EPA, OSHA is still without a leader, as Scott Mugno waits for the Senate to act on his appointment.

“That’s good,” said Berkowitz of the delay.”The director could take it in a very right-wing direction.”

Despite OSHA’s leaderless status, Berkowitz, Barab and other close watchers of the agency still have noticed some shifts.

Trump has fewer federal OSHA inspectors working. In January 2018, OSHA employed 764 inspectors, while it had 814 just as Trump was being inaugurated in 2017, Berkowitz discovered via a Freedom of Information Act request. (New York and some other states also perform their own OSHA inspections; this article tallies federal activity only.)

These inspectors were doing more visits—about 1.5 percent more in 2017 than in 2016 (but less compared to any other Obama-era year). But they were performing less actual inspection, by focusing on less complicated sites.

This move toward less complicated inspections is revealed by counting enforcement units, a measure that’s intended to capture inspection complexity. Enforcement units were adopted as a metric for fiscal year 2016 under Obama to give inspectors credit for the actual time and effort that their tasks require. An intricate process-safety management inspection of a large chemical facility, for instance, yields seven enforcement units, whereas a federal agency inspection nets only two.

Counting enforcement units was meant to promote a shift toward tougher cases, according to health & safety observers and OSHA’s website . The new system emphasizes “resource-intensive enforcement activity” that focuses on crucial workplace “issues” such as ergonomics, heat, chemical exposures, workplace violence, and process-safety management, according to the OSHA site.

Nationwide, comparing activity from October 2016 to February 2017 to activity from October 2017 to February 2018, Berkowitz found via her FOIA that the agency’s enforcement units had dropped about 7 percent.

The previous administration also shifted some of its focus toward work sites where issues were already known or alleged. These unprogrammed inspections result from employee complaints, injuries, fatalities, and referrals. By contrast, OSHA’s programmed inspections methodically spot-check job sites according to a schedule that reflects the agency’s relative priorities for various industries.

During the Obama Administration, the raw number of programmed inspections decreased by 27 percent from 2011 to 2016. During that same period, unprogrammed inspections rose by 11 percent. Overall, the total number of inspections dropped by 31 percent during Obama’s presidency.

This shift toward unprogrammed inspections stemmed at least partially from the 2015 adoption of a rule that required employers to report to OSHA any “severe” work-related injuries, ones that resulted in hospitalization or amputation. That broader reporting requirement spurred more of these inspections.

(At least in New York, the share of programmed inspections has crept back up—from 39 and 38 percent in 2015 and 2016, respectively, to 48 and 41 percent in 2017 and 2018.)

Under Trump, the OSHA has also effected new policies by changing its interpretation of standing rules. For one, it took the teeth out of an Obama-era rule that prevented companies from performing drug tests on employees who are reporting a work-related injury or illness.

Also, the Congressional Review Act of 2017 nullified the Volks Rule, which had required companies to maintain records of work-related illnesses and injuries for five years.

A 2016 rule required companies with more than 250 employees to submit detailed injury and illness logs electronically to a central public database. Now, if a proposed change to that rule goes forward, the companies will still have to maintain the records—known as OSHA 300 logs—but need not submit them. Some believe that this policy could stymie efforts by workers to maintain anonymity while checking the health and safety record of their own workplaces.

“Workers feel that they will be intimidated if they request those logs,” said Micki Siegel de Hernández, health and safety director for District 1 of the Communications Workers of America union, which represents workers as varied as airline gate agents and hat factory workers.

Under the Trump administration, OSHA’s six-year-old Whistleblower Advisory Committee went dormant as the president ordered a review of the structure of the entire executive branch in March 2017. It’s one of five OSHA advisory boards that have suffered a similar fate.

Employers See Little Change

As the agency changes course under Trump, those who represent employers still doubt that OSHA has become more business-friendly with respect to its policies on inspections and assessing penalties.

“We’re not seeing relief or any sort of policy to take a lighter touch with employers or work collaboratively with them,” said Ben Briggs, a lawyer with Seyfarth Shaw in Atlanta, who represents employers in OSHA enforcement matters.

Briggs acknowledges that OSHA is working with fewer inspectors, but, he says, “They’re doing more with less.”

Get the best of City Limits news in your inbox.

Select any of our free weekly newsletters and stay informed on the latest policy-focused, independent news.

That impression is certainly reflected in OSHA’s raw inspection numbers and its public stance. On its website, OSHA continues to tout its big-money enforcement penalties. After a brief lull early in the Trump administration, OSHA returned to the Obama-era policy of issuing a press release about every inspection resulting in over $40,000 in penalties.

For example, in July, OSHA levied $182,917 in initial finesagainst Timberline Hardwood Floors, a Fulton, New York-based manufacturer of custom flooring. The company’s employees, some of them untrained forklift operators, were working in an environment with exposed electrical circuits and unlabeled hazardous materials and chemicals, among other potential dangers.

A collection of penalties above $40,000 is far from the norm, however.

“That’s the end of the distribution, statistically. That’s the 1 percentile or less,” said Eric Frumin, safety and health director for Change to Win, a federation of labor unions.

On August 1, 2016, OSHA increased by 78 percent the amounts it fined employers, a change that perhaps drives the perception among employers that the agency has not taken its foot off the gas. The agency had not raised the penalty rates since 1990, so this adjustment for inflation was both steep and overdue.

Even with that raise, New York Committee for Occupational Safety & Health found in a study that in construction fatality cases in New York, average fines actually went down 7 percent in 2017.

Workers also die and suffer serious injuries at sites that are not typically considered “dangerous.” On April 2 of last year at KP Farm Market in East Flatbush, Brooklyn, a makeshift hoist crushed the jaw and neck of delivery worker Young-Kil Sim, killing him. OSHA fined the market for violating two stairway-related provisions, a machine-guarding rule, and a general requirement for employers to keep workplaces free of deadly hazards.

“Employees were exposed to a crushing hazard while operating a lift to transport good [sic] & people between floors,” read the OSHA inspector’s notes on the last violation.

For that violation and the three others, KP Farm Market was fined a total of $16,260, which was subsequently reduced to $10,000.

Though they are not meant to right wrongs, OSHA penalties have been shown to prevent certain types of injuries. A 2010 study led by two RAND researchers examined the correlations between injuries on jobsites in Pennsylvania and OSHA inspections on those same sites from 1998 to 2005. It found that inspections with penalties related to the use of safety gear had the greatest effect on preventing future injuries, and that OSHA inspections with penalties improved jobsite safety even outside the standards that were being investigated.

OSHA Activity in New York Under Trump

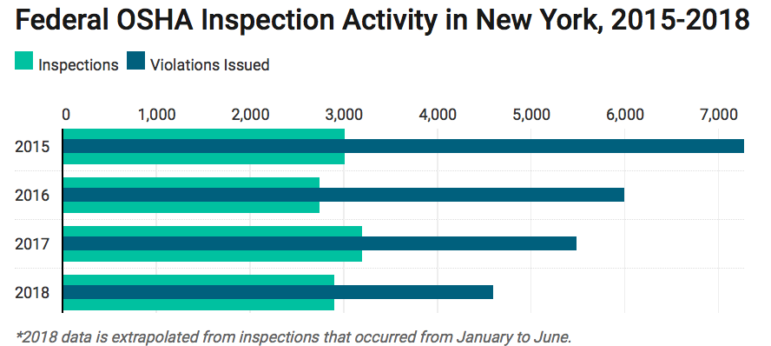

Though nationwide OSHA inspection activity is down in terms of enforcement units, the raw number of inspections in New York has gone up since Obama left office: 3,201 federal inspections in 2017, versus 2,744 in 2016 and 3,014 in 2015.

Federal OSHA inspections in New York have yielded far fewer violations, however, since the advent of the Trump Administration. The number actually started falling in 2016, when, during the last full year of the Obama Administration, OSHA decided to focus on doing more complicated inspections and fewer of them. In 2015 OSHA performed 3,014 inspections and issued 7,281 violations in New York, about 2.4 per visit; in 2016, it did 2,644 inspections and issued 6,004 violations, or 2.3 per visit.

But that drop in issued violations continued under Trump, even as the agency changed course again and began doing more inspections. In 2017, its inspectors performed 3,201 inspections and issued 5,492 violations, about 1.7 per visit.

By now, almost all violations have been issued for inspections through June 2018. Based on activity from the first half of the year, federal OSHA inspectors in New York are on track to issue still fewer violations compared to 2017. The number of inspections in 2018 will surpass that of 2016, while, if the current pace continues, yielding just over three quarters the violations.

“OSHA’s performance has been pretty consistent over the years. Their supervision of inspectors has been pretty consistent,” said Frumin. “And when we see changes in the outcomes – we see a drop in the number of violations that inspectors are typically finding – it certainly raises the question, well, who’s minding the store?”

Violations in New York State have not only decreased in number, they’ve come down in price, once you account for the 2016 increase for inflation. As mentioned, on August 1, 2016, OSHA boosted the entire violation fee structure by 78 percent, to cover inflation since 1990.

The median violation from a 2015 inspection would have cost an employer $1,780, after any discounts from settlements or rulings and applying the inflation adjustment. For 2016 inspections, that rose to $1,899.63.

Under Trump, the median final violation amount dropped 12.5 percent to $1,662 in 2017. For 2018, because so many cases are still open and subject to future penalty reductions, it’s premature to assess the “current” penalties. However, the median discount for penalties from closed cases has remained the same since 2016, at about 30 percent. And the median initial penalty (again, adjusted for inflation when necessary) has dropped from $3,560 in 2015 and 2016 to $2,772 in 2017 and 2018.

OSHA ‘Laying Low’?

In addition to changes to OSHA that flow from new policies, there’s an indirect effect of the Trump Administration that especially hits immigrant-heavy states such as New York. Leaders from the Laundry Workers Center, an organizing group for laundry, warehouse and food-service workers, said that under Trump, undocumented immigrants are much less likely to call OSHA, even when there’s an obvious violation. That’s because they now fear, in addition to reprisal from employers, any contact with the federal government.

“I know that people are more scared to file a complaint against employers for OSHA,” said Rosanna Rodriguez, co-executive director of the Laundry Workers Center. “Before it was a challenge, too—imagine now.”

Mahoma Lopez, the other co-executive director of Laundry Workers Center, gave the example of a woman in her 50s from Mexico who was working alone in a Laundromat in Brooklyn. One day she mixed ammonia and bleach and had trouble breathing. She had to pay thousands in medical expenses out of pocket, Lopez said, but the worker didn’t want to give her phone number to the Laundry Workers Center, let alone pursue an OSHA complaint.

Whether or not they might welcome it, workers across the country operate with less scrutiny over their worksites than they did during the previous administration, as OSHA is less active as measured by enforcement units. And in New York State at least, employers are finding friendlier treatment from OSHA inspectors, who are issuing far fewer violations.

An OSHA spokesperson emphasized that the agency was performing more inspections under Trump than in the last year of the Obama Administration. The agency did not address what might have produced the dip in the number and the median amounts of penalties issued in New York under the Trump Administration.

“There has been no change in how monetary penalties are applied,” the spokesperson wrote in a statement.

As for staffing, the OSHA spokesperson said that the agency hired more inspectors in the fiscal year ending in October 2018 and planned to continue this increased hiring in fiscal 2019, butdid not provide numbers.

“Folks at OSHA who try and do what they can under the agency’s limitations still try and do the same things, but kind of lay low,” said Siegel de Hernández.

Morale at the agency is low, according to Barab, the former OSHA official.

“People are feeling neglected,” he said. “There’s not much happening there.”

One thought on “Federal Work Safety Inspectors Have Eased Penalties in NY Under Trump”

Pingback: Federal Work Safety Inspectors Have Eased Penalties in NY Under Trump - Sage Shield Safety Consultants Pte Ltd