Sophie Putka

The statue of J. Marion Sims is gone. But its pedestal remains.

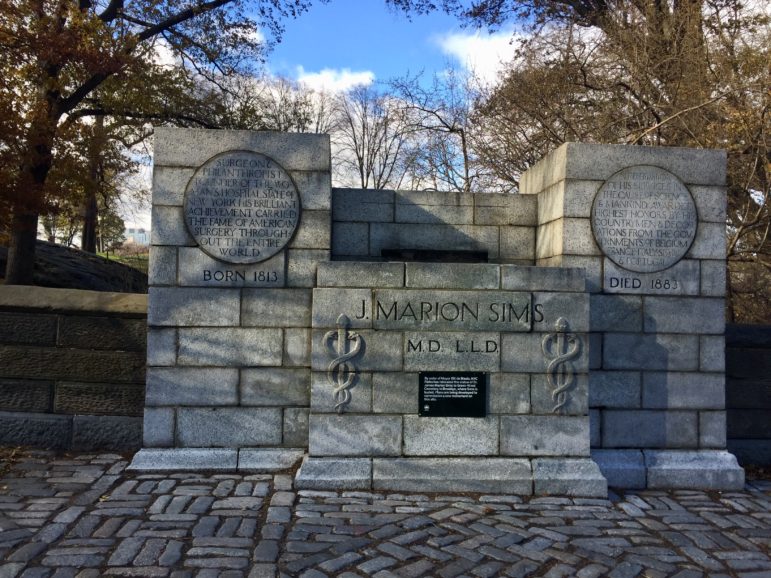

Across the street from the Museum of the City of New York, now showing an exhibition called “Activist New York,” a small black plaque rests on the front of a stone pedestal inscribed with the name of J. Marion Sims. The message notes the removal of a statue by order of the mayor. It does little to hide the vast expanse of stone towering on the edge of Central Park.

Nearly eight months have passed since the bronze statue of the physician, who experimented on enslaved women without anesthesia and later became known as the “father of modern gynecology,” was removed after years of activism by East Harlem community organizations and residents, including East Harlem Preservation, El Museo Del Barrio, the New York Academy of Medicine, and Black Youth Project 100 (BYP100).

But while stakeholders deliberate on plans for new art, critics say the nagging presence of the pedestal lingers. Marina Ortiz, president of the East Harlem Preservation, which largely led the charge on the campaign to remove Sims, says removing the statue without the pedestal wasn’t enough.

“We don’t understand why they left that platform in place, with his name and a little silly plaque underneath,” Ortiz says. “Just having that structure there, even if they were to sand it down, remove his name, it just inhibits what kind of new artwork can be placed there.”

Kendal Henry, director of Percent for Art Program which will fund the artwork that rises in Sims’ old space through the Department of Cultural Affairs, says that the decision to remove the pedestal would ultimately be “up to the artist.” But both the artist and their proposal for art, which would have to factor in all costs including the potential base removal, must pass a vote by an “artist selection panel” first, Henry says.

The panel will consist of the Parks Department, the Department of Cultural Affairs, a city design agency, and three outside “arts professionals” to be selected by the commissioner of Cultural Affairs, with community-based organizations and the community board consigned to a purely advisory role, Henry says.

This means the panel could do away with any proposals that ask for funding to remove the base, and that the winning artist proposal could have to incorporate the base into their artwork.

“Keeping it doesn’t necessarily mean exposing it for what it is. It could be completely covering it up with tons of lights or camouflaging it,” Henry says. “You know if you have a bad tattoo, it’s still there, but you may not see it because it’s covered up.”

Advocates who successfully fought to remove Sims’ statue feel the city’s choice to remove only the statue without the base is insulting. Ortiz blamed the city’s decision on an attempt to pacify people who were opposed to removing the statue in the first place. In a piece for Liberation News, the Party for Socialism and Liberation newspaper, Ortiz wrote, “the city has chosen to keep the Sims pedestal (and signage) in place as a clear conciliation to conservative critics.”

Other activists aren’t as sure what will remain of the base, but want the painful reminder of Sims gone.

“The responses that we’ve heard so far is that they don’t want really to see anything, any remnant of his presence, and I think that does include his name, especially when you have 11 other unnamed women that he practiced on,” says Ngozi Alston, organizing chair at BYP100’s New York chapter, which took a lead role among the groups that pushed for the Sims statue removal.

The statue’s legacy was so toxic that even at its planned new destination, Green-Wood Cemetery in Brooklyn — where Sims is buried — a group called the Concerned Neighbors of the Green-Wood Cemetery began a letter campaign to stop it.

“We demand that the J. Marion Sims statue not be relocated to Green-Wood Cemetery,” their online petition stated. “There is no space for honoring white supremacy in our neighborhood.”

A Green-Wood Cemetery spokesperson said this month that the statue is still in storage, and that there is no date set for its re-installation at Green-Wood Cemetery.

“As a National Historic Landmark, the responsibility to preserve this history, and not to whitewash it, is something Green-Wood takes very seriously,” Green-Wood Cemetery president, Richard J. Moylan, said in a statement.

Community groups and institutions in a group called the Committee to Empower Voices for Healing and Equity, which includes the Department of Cultural affairs and the Parks Department, have launched a series of public conversations to brainstorm new art for the statue’s former location and gather input from interested neighbors.

An open call for to artists is due out from Dec. 21 of this year to Jan. 31, 2019 with plans to install the new piece in the summer of 2020.

“The artist selection plays a huge role in — I don’t want to say justice, but in starting to heal this terrifying thing that’s been imposed as a fixture of this community for years,” Alston says.

A number of community members and activists say they want the art to center around women of color. Diane Collier was the Community Board 11 chair from 2015 to 2017, when she says she urged the board to take a position against the statue. She’d like the new art to educate passers by about the contributions of women of color to science throughout history.

“It would attract people when they’re passing to ask, ‘who is that woman?'” Collier says. “There were women who were scientists and women who were doctors, and you never know about them until they make a movie about them like ‘Hidden Figures.'”

In a statement, the Department of Cultural Affairs told City Limits: “The removal of the J. Marion Sims statue last year was just the beginning of the long process of reckoning with his painful legacy. Following two public forums, the city continues to work closely with the Committee to Empower Voices for Healing and Equity to drive the conversation about what comes next. The artist selected to design a new permanent artwork will work with local residents to ensure that the monument they create is something that responds to the communities’ desire to address and ultimately move beyond the scars of the past.”*

City Limits’ reporting on the intersection of art and policy is supported by the Laurie M. Tisch Illumination Fund. City Limits is solely responsible for all content.

* This statement was provided after the original version of this story was published.