Mike Groll/Office of Governor Andrew M. Cuomo)

Last week, the governor toured the modernized Rochester airport. Spending on infrastructure has been a highlight of his economic program.

This is one in a series of articles looking at the policy positions of the men and woman running to be governor of New York State.

* * *

From the depths of winter and through a long and lonely summer and fall, Marcus Molinaro has been walking a tight-rope. The Dutchess County executive has tried to distinguish himself from President Trump without alienating the conservatives whose votes he needs if he’s going to make a respectable showing on Tuesday against Gov. Andrew Cuomo.

To that end, the Republican nominee has said he now supports LGBTQ rights and could back new protections for abortion rights in state law, criticized Cuomo’s SAFE Act but refused to take money from the National Rifle Association, said he didn’t vote for Trump but declined to denounce him. Stressing his humble roots—his family relied on food stamps during part of his youth—Molinaro has presented himself as a moderate problem solver, an “everyday New Yorker” more interested in rolling up his sleeves than in Republican orthodoxy.

But when it comes to his plans for the economy, Molinaro’s plans come straight out of the traditional Republican playbook of tax cuts, restrictions on government spending and rollbacks of regulations.

His chief opponent is harder to categorize. Cuomo entered office in the aftermath of the financial crisis stressing the need for fiscal discipline, ordering spending cuts, pushing tax reductions and picking fights with unions. Later, he ordered massive public investments in infrastructure, organized economic development around regional councils, and endorsed the creation of four upstate casinos. In his second term, he moved to support a higher minimum wage.

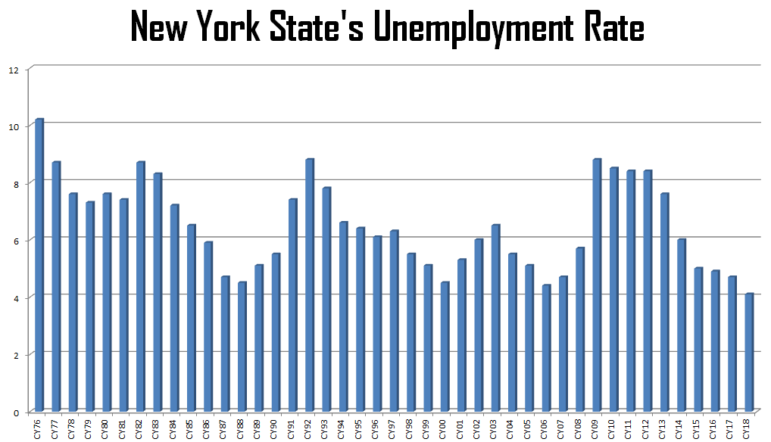

Unemployment rate for September of each year, per the U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics.

From crisis to …?

In his first State of the State address in 2011, Cuomo declared: “[W]e have to relearn the lesson our founders knew and we have to put up a sign that says New York is open for business. We get it. And this is going to be a business friendly State.” In that address, Cuomo called for a property tax cap, the creation of 12 regional economic development councils, consolidating the departments of insurance and banking and consumer protection into a single agency and an “urban green markets program.” He also pledged to tackle “unfunded mandates” in which the state forces counties and towns to provide services but doesn’t help pay for them.

Over the years, there have been dozens of new proposals. In year two (2012), Cuomo proposed building the nation’s largest convention center—which never happened—and the Buffalo Billion program, which did occur. 2013 saw a focus on upstate tourism: a call for casinos, the launch of the “taste of New York program” and other steps to boost upstate tourism and agriculture.

“We need to eliminate the regulatory barriers … that are barriers to business growth,” he declared in 2014, when he called for a commission to dismantle those regulations. A small business tax cut was among the new ideas in 2015. The $100 million “Built to Lead” infrastructure investment program was a headline of his 2016 speech, while in 201, a middle-class child-care tax credit was one of his new ideas.

Broadly speaking, the state’s economy has improved since Cuomo took office: The unemployment rate has fallen steadily, the number of jobs has increased to an all-time high, and the number of people out of work but looking for employment is at its lowest level since 2001. This is in line with national trends. The state’s unemployment rate of 4.1 percent is higher than the national average and the state’s labor-force participation rate—the share of the population either working or looking for work—is lower than that of 38 other states.

While the state’s population increased by about 470,000 between 2010 and 2017, that growth was fueled by natural increases and international arrivals. More than a million people left New York for other U.S. states during that period. Among New York’s 62 counties, only 17 (including the five city boroughs) saw population growth over the 2010-2017 period. Had it not been for the growth in the city and Westchester County, the Empire State would have shrunk during Cuomo’s two terms.

2010-2017

The state’s poverty rate fell from 14.9 percent in 2010 to 14.1 percent in 2017—a drop of 0.8. The national poverty rate fell by 1.9 points over that span. New York’s child poverty rate moved from 21.2 percent in 2010 to 19.7 percent last year, a drop of 1.5 points (the national child poverty rate, now 18.4 percent, fell 3.2 points during that period). In raw numbers, about 100,000 fewer children and 100,000 fewer adults between the ages of 18 and 64 live below the poverty line in New York now compared with the year before Cuomo become governor; roughly 50,000 more senior citizens in New York now live in poverty versus 2010.

In his most recent annual address, delivered early in 2018, Cuomo pointed to his economic record with pride – noting that “every New Yorker’s tax rate is lower today than when I took office” and that the state has its “highest credit rating in 40 years.” Others also praise his overall record: In its endorsement of the governor for re-election, the New York Times said that his accomplishments include “increasing the minimum wage, implementing paid family leave and setting to work rebuilding some of New York City’s most essential infrastructure.”

In a recent report, the Citizens Budget Commission, a fiscally conservative think tank, said that under Cuomo state operational spending grew “at an average pace of 2.8 percent annually, since fiscal year 2011.”

“State leaders met their goal to keep SOS below 2 percent in the early years of the Cuomo administration; however, in the last two years, spending restraint has loosened,” the report read. “Overall, state growth in spending is in line with other states, if not slightly lower.”

Cuomo has devoted significant attention and money to improving the upstate economy, though results have been mixed. Casinos were supposed to bring in $430 million in tax revenue a year. So far, over three years, the four casinos have paid about $226 million in taxes. Aside from the corruption convictions related to the Buffalo Billion, the program has garnered both praise and scorn. Even Molinaro praises Cuomo’s property tax cap, although there are complaints that the state hasn’t done as much to relieve some of the Albany mandates that drive local spending. And it remains to be seen if steps like the voluntary payroll tax, implemented to reduce the adverse impact of the Trump tax law on New York taxpayers, will get traction.

A $17 billion plan

Molinaro for Governor

Molinaro has served as the executive of Dutchess County since 2012.

Molinaro’s critique of the Cuomo economic record has two major thrusts. One criticizes the governor’s spending on economic development, which Molinaro says are “rife with corruption and incompetence.” The other faults Cuomo for failing to do enough to relieve New York’s combined local and state tax burden, which is among the highest in the country.

On the first front, the Republican proposes halting all economic development spending until new controls are put in place to ensure transparency and integrity. Molinaro also wants to see an end to direct grant funding to corporations.

The Republican nominee says his tax plan would result in $17 billion in savings. Molinaro’s primary focus is on property taxes. He wants to make Cuomo’s tax-cap permanent—and extend it to New York City—as well as to reduce unfunded mandates: Among the state laws he blames for driving up the costs of local government are the Wicks Law, which requires multiple contractors on many public works projects and Molinaro wants to repeal, and the prevailing wage law, which he wants to reform. He further proposes that the state take over the costs of Medicaid, providing lawyers for low-income defendants, early intervention services and more.

One tax Molinaro hopes to expand is the sales tax, which he advocates applying to “remote sellers without a physical presence in New York State,” which he estimates would raise about $350 million a year for the state and cities. Molinaro also wants to allow localities more freedom to adjust their sales taxes, and to eliminate the sales tax exemption for clothing, because, “The concept, although well meaning, has provided little evidence of increased economic output and is poorly targeted to help families in need.”

Molinaro proposes reworking the way state taxes are calculated to give a break to families earning between $107,650 and $323,200 a year. He wants to eliminate the tax on utilities, allow the millionaire’s tax to sunset and—obscurely citing a 2007 Connecticut study indicating that people leave states because of estate taxes—calls for eventually eliminating that tax in New York. He wants to double the rate at which employers can deduct wage costs from their business expenses and apply the existing zero tax rate for some manufacturers to a broader set of industrial firms. Molinaro proposes increasing the child-tax credit and the earned-income tax credit—including making the latter, which helps low-income families, available to people without children.

It’s unclear what the combination of increased state responsibility for local spending and decreased state revenues because of tax cuts would do to the state’s bottom line. Perhaps most significantly, Molinaro wants to codify a cap on state spending and require a supermajority of the legislature to pass future tax hikes—ideas that would significantly restrict the ability of Albany to respond to changing economic conditions.

The other three candidates for governor, Green Party nominee Howie Hawkins, Libertarian candidate Larry Sharpe and Serve America’s Stephanie Miner, agree with Molinaro on the need to address the way the state imposes costs on counties and towns: Hawkins and Sharpe both call out “unfunded mandates” and Miner calls for the state to take over Medicaid. It’s there that agreement among the four challengers ends.

Miner calls for cutting property taxes “to relieve the crushing burden that is crippling local governments and driving residents out of New York” and says she wants to “slash the parts of the state’s vast bureaucracy that waste public money, delivering little to no value for New York taxpayers,” although her literature offers little detail.

Hawkins says as governor he’d promote workers’ cooperatives, remove the property tax cap, revive a stock transfer tax and “create a state-owned bank, with local branches, to finance public projects, private businesses, and consumer loans at lower cost than private banks,” among other policies.

Among a long list of ideas, Sharpe says he would “end the subsidies currently given to major corporations that move in, wreck local and small businesses and leave,” and look for new forms of revenue to permit tax cuts. One idea: charging shipping firms to move freight along mass-transit lines that are underused at night and “taking action to make the Erie Canal commercially viable again.”

City Limits is a nonprofit.

Support from readers like you allows us to report more.