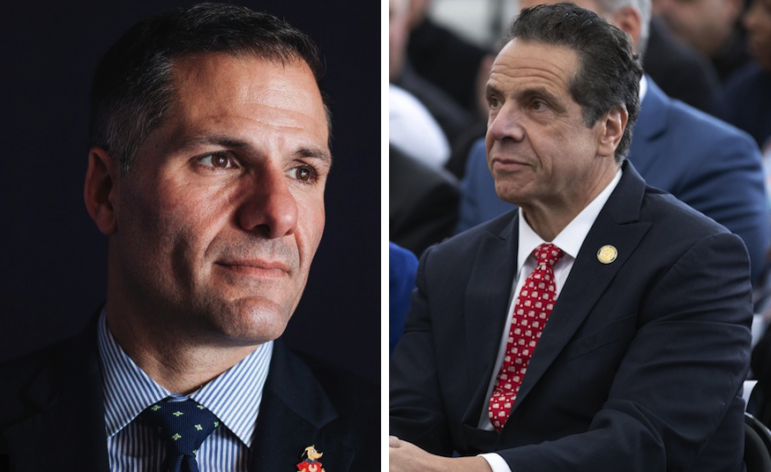

Molinaro for New York; Office of the Governor

The Republican/Conservative/Reform candidate for governor and Dutchess County Executive Marcus Molinaro and Gov. Andrew Cuomo, nominee of the Democratic, Working Families and Independence Party lines.

This is one in a series of articles looking at the policy positions of the men and woman running to be governor of New York State.

The gubernatorial race is nearing its end, and Governor Andrew Cuomo and GOP candidate Marc Molinaro have become more combative as they take on each others’ policy positions and ethics on the campaign trail.

While they engaged in a testy back and forth during their October debate on CBS, both Molinaro and Cuomo have in common a long history in politics. Cuomo was campaign manager for his father, then assistant secretary for the U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development before becoming Secretary for the federal agency. In 2006, Cuomo was elected Attorney General of New York and now is seeking his third term as Governor. Molinaro entered the world of local politics at the age of eighteen when he sat on the board of trustees in Tivoli, a township in upstate Hudson River, and one year later became the town’s mayor and county legislator. From 2007 to 2011, he served as state Assemblyman. Molinaro is currently serving as the Dutchess county executive while running his gubernatorial campaign.

While both have decades of political experience, their respective campaign contributions reflect different worlds. Cuomo’s campaign opened the year with $25 million in the bank, raised $13.7 million over the course of 2018, and had $16 million on hand at last count. In comparison, Molinaro’s campaign has run on a shoestring. He has raised $1.9 million and had $311,000 at last report.

But real-estate related donations form a big part of both their war chests. Molinaro’s largest contributions include $44,000 each from the Neighborhood Preservation Political Action Fund and Rent Stabilization Association—both are associated with pro-landlord groups. Cuomo has in 2018 raised $3 million from limited liability corporations, or LLCs, which are usually linked to properties.

The common thread of real-estate money should be no surprise: Several issues involving housing and development will be on the plate for whoever is governor in 2019, and the candidates have expressed divergent opinions on many of them.

Property taxes

Taxation and revenue collection are governed by a complicated network of local, state, and federal laws. The state established a tax levy limit in 2011 better known as a property tax cap that affects all local governments (including counties, cities, towns, villages and fire districts) and school districts across the state except the five city boroughs, and school districts of Yonkers, Buffalo, Rochester and Syracuse.

According to the State Comptroller’s office, the property taxes levied by affected local governments and school districts generally cannot increase by more than 2 percent, or the rate of inflation, whichever is lower. The property tax cap bill does allow local governments and school districts to levy an additional amount for certain excludable expenditures and the possibility of overriding a levy limit is permitted.

Despite the combative campaigns between Cuomo and Molinaro, even the GOP contender lauded Cuomo for the cap on property tax hikes — but Molinaro wants to take it a step further by expanding the property tax cap. According to Molinaro’s campaign website, he proposes to make the property tax cap permanent and expand it to include New York City and the dependent school districts. This would save property owners an estimated 30 percent in taxes, according to Molinaro’s campaign, which contends, “if this cap had been put in place when the statewide cap was enacted, city residents would have saved almost $17 billion through 2017.”

Molinaro supports “tax fairness,”a way to ensure that homeowners are not subjected to increases in property taxes and/or that property taxes are not unfairly shifted to commercial properties and renters. He highlighted a September study from the City Comptroller’s office which reported the city’s tax assessment system was unfair to low-income and minority communities; Molinaro supports establishing a New York City Property Tax Reform Study Commission. In May, the De Blasio administration created the Advisory Commission on Property Tax Reform, which is reviewing the property tax system.

Cuomo plans on continuing with his is property tax cap along with existing property tax programs such as the Property Tax Freeze which reimburses qualifying homeowners for increases in local property taxes on their primary residences and Property Tax Relief Credit which reduces the property tax burden of a qualifying homeowner in his State of the State address last year in December.

But the property tax cap does not come without caution from experts. A study from the Long Island Regional Planning Council released in April said the property tax cap would not be sustainable in the long run: “With the cap in place, the projected burden grows from 8.8 percent in 2015 to 9.5 percent in 2035. The key question is whether this is sustainable over the long run as compliance with the cap has been aided by a number of factors…”

The study outlined factors that should be taken into account before continuing with the tax cap such as a rise in property values; a decline in pension payments for governments and schools; depletion of government and school district reserves accumulated prior to the tax cap; a stabilization or even decline in school enrollment; a greater increase in state school aid which has grown faster than property tax increases; and savings from the retirement of senior employees and teachers who are being replaced by entry-level personnel.

Rent regulations

Nearly a million apartments in the city and several thousand in other urban areas in the state are under rent stabilization, which requires landlords to change rents in accordance with guidelines passed by a local board, in the city’s case the Rent Guidelines Board. Rent-stabilized units are seen as a key bulwark against displacement, but tens of thousands of these apartments have disappeared from the program under changes in state law in the 1990s. These guidelines are set to expire in June 2019.

Four features of the rent-stabilization system have been in the spotlight in recent years. One is high-rent or high-income vacancy decontrol, by which a rent-stabilized unit leaves the program if its rent exceeds $2,700 or the tenant-household’s income exceeds $200,000. Another is the vacancy bonus, which allows landlords to boost rent by 20 percent every time a lease changes hands. A third is preferential rent, which is when an owner charges less than the legal rent–creating the threat of a sudden, massive increase in rent far larger than the year-to-year increases approved by the rent guidelines board. Finally, Major Capital Improvements are when property owners increase rents based on the costs of improvements or installations to a building: tenant advocates say these increases often end up generating far more revenue–at the tenants’ expense–than the MCI cost.

During his nearly eight years in office, Cuomo has signed legislation raising the income threshold for decontrol from $175,000 to $200,000 and the rent threshold from $2,000 to $2,700, with future increases indexed to the percentage increases in rents on one-year leases approved by the Rent Guidelines Board. The vacancy bonus was limited to one use per calendar year. The two rent law renewals approved by Cuomo (in 2011 and 2015) also tightened up the rules on how landlords pass the costs of individual apartment improvements and major capital improvements on to tenants. Moving forward, Cuomo’s campaign says the governor wants to end vacancy decontrol, make preferential rent the legal rent, make the surcharges for apartment and building improvements temporary rather than permanent, and “further limit or eliminate vacancy bonuses to ensure landlords aren’t rewarded financially for schemes to force tenants out.”

On tenant harassment, Cuomo would like to increase monetary penalties imposed on landlords who harass tenants by approximately $1,000, to $3,000 for each offense and up to $11,000 for each offense where the owner harassed a tenant to obtain a vacancy. Cuomo created the first state Tenant Protection Unit to audit and investigate landlord wrongdoing and has given additional funding to state housing programs such as the Department of Homes and Community Renewal which functions to build, preserve and protect affordable housing and increase home ownership across the state.

Molinaro’s campaign has largely been quiet on rent regulations but as state Assemblyman he voted consistently against rent regulations. In 2009, Molinaro voted “nay”against bills raising the income and rent thresholds for deregulation, expanding rent control and giving cities more control of their rent laws.

Subsidized housing

In 2017, Cuomo launched a five-year, $20 billion housing plan aimed at creating 100,000 affordable units, with many targeted to the homeless.

Now in its third phase, the plan has included $200 million for projects and improvements related at housing developments owned or operated by NYCHA; $100 million for the construction and preservation of 100 percent affordable units in the city; $125 million for developing or rehabilitating affordable housing targeted to low-income seniors, aged 60 and above; $75 million to preserve and improve Mitchell-Lama properties; $41.5 million for promoting home ownership among families of low and moderate income; and $10 million for stimulating reinvestment in properties located within mixed-use commercial districts located in urban, small town, and rural areas of the state.

The plan includes an estimated $950 million to create 6,000 new supportive housing beds. The supporting housing program includes parenting education, counseling, independent living skills training, primary healthcare, substance use disorder treatment and mental health care, child care employment and training opportunities and benefits advocacy for supportive housing tenants, according to the state Division for Homes and Community Renew.

Under the Cuomo administration, the 1971 421-A tax abatement program for developers was revamped in 2016. The program gives developers a tax exemption for building a multi-family residential project. The key changes Cuomo made to the program was the establishment of construction wage minimums for some projects built with the tax break. While the real-estate industry welcomed the resumption of the program after a brief pause, many housing advocates believe it is an inefficient way to build affordable housing.

Molinaro does not go into detail on how to abate the homeless crisis in New York in his proposal on his campaign website but did say during the CBS debate that services should be expanded to those with disabilities and mental health issues. On homelessness, Molinaro says His childhood has shaped his position: He comes from a social services background and grew up on food stamps.

Howie Hawkins, the Green Party nominee for governor, has called for eliminating 421-a (which he considers a giveaway to developers), expanding rent regulation statewide, creating new public housing, giving New York City control over its own rent laws and imposing a moratorium on foreclosures.

City Limits is a nonprofit.

Support from readers like you allows us to report more.