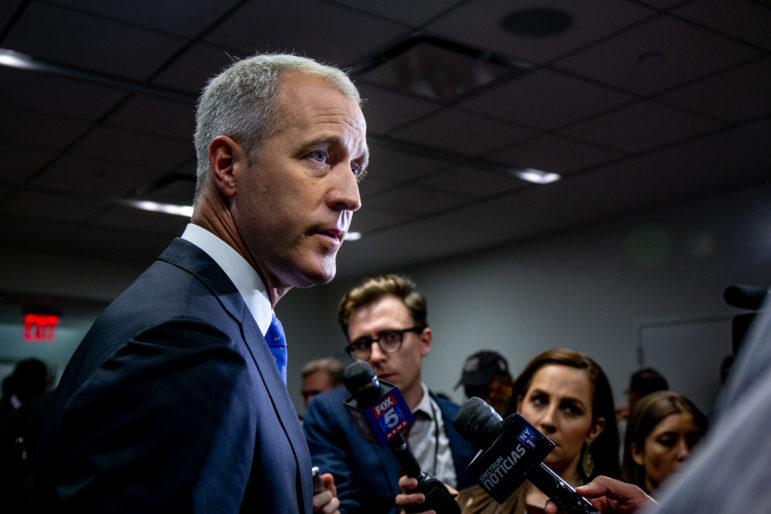

Adi Talwar

Sean Patrick Maloney speaking with the press after the New York State Attorney General Democratic primary candidates debate on August 28th.

The Democratic attorney general primary on September 13 features four candidates with similar ideologies but very different backgrounds. In a four-part series this week, City Limits takes a look at each candidate’s career for clues about how they might approach being “the people’s lawyer.”

Congressman Sean Patrick Maloney arrived early August 27th at The Bagel Market, a small shop on 7th Avenue between Union and Market in Park Slope. Hungry but affable, he chats with staffers, then orders a bagel before sitting down for his scheduled town hall. It’s 8:15 a.m. and it’s his second town hall of the day; he’s fresh from one of his “running town halls,” a series of morning jogs in which the congressman answers questions from folks who are up for a brisk jog and who are interested in learning more about his attorney general run.

With no time between town halls for an outfit change, Maloney arrives at The Bagel Market in grey running shoes with bright neon green laces, a sky-blue Nike windbreaker and black Nike running shorts that reveal his tall frame and skinny legs. The Bagel Market holds only 7 tiny square tables, and there are about 6 people here to see Maloney when he arrives – it doubles to about 14 people as the hour progresses.

He sits down at a cramped table across from an older woman and immediately starts answering her first question while simultaneously chomping on a bagel, prompting a request from a staffer to speak up a bit, and another lighthearted suggestion from an attendee who asks if he wants to finish eating first. “So elegant,” he says sarcastically, mocking himself for talking with his mouthful.

The intimate setting caters to Maloney’s strengths. He’s personable and chatty, rolls his g’s when he talks, curses in media interviews. At the town hall he chats effortlessly, is self-effacing and acknowledges everyone in the room one by one. He asks for a show of hands of who is at the bagel shop to meet him, saying he doesn’t want to “ruin anyone’s breakfast.” A customer opens the door to the tiny shop, unaware that a town hall is taking place, then seems to back away scared when he sees an event in progress. Maloney apologizes and gestures for him to enter, saying, “You’re okay.”

His personability is one reason he believes he’s been able to have his feet in two worlds, courting a record he believes is bipartisan but rooted in progressive ideas. In his attorney general run, he touts frequently that he has won “tough elections” against Republicans, citing the fact that the congressional district he represents, the 18th, went for Trump in the 2016 elections. Winning in a district like that isn’t a given, his ads say, for an openly gay white man who has adopted black and Latino children.

But some of Maloney’s votes and prior stances may find tension with the left-leaning energy that is invigorating corners of the Democratic Party, where existing power structures, once taken for granted as part of Democratic orthodoxy, have come under sharper scrutiny.

He co-authored legislation on criminal justice reform meant to divert opiate addicts from the criminal just system and, like all three of his competitors, wants to abolish cash bail. He also voted for the Protect and Serve Act, one of many Blue Lives Matter-style bills across the country that would make it a federal crime to assault a police officer.

He cites the deportation of a former staffer’s father, one which lead to the man’s death, as the chief reason he is running for attorney general despite being a sitting congressman potentially running for reelection. The staffer in question appears with him in an emotional TV spot. But unlike his opponents Zephyr Teachout and Tish James, he doesn’t advocate the abolition of ICE, suggesting they and Customs and Border Patrol have a role to play in public safety.

He co-sponsored a bill to end the Muslim Ban but voted for the 2015 Securing Against Foreign Enemies Act, which earned a rebuke from critics like the ACLU for opening the legislative door to such a ban.

A crowded field

Maloney has taken to saying his bipartisan voting record is a “feature, not a bug,” and a sign that he’s able to win progressive victories with tough crowds. And it’s true that his voting record is less checkered on progressive issues than might be expected from an upstate Democrat winning elections in what some might consider Trump country; a 538 analysis suggests he voted with Trump 34 percent of the time , but many of the votes listed are on issues with bipartisan support.

Speaking to City Limits, he says he sees no contradiction in some of his views, particularly around law enforcement or ICE, saying, “I don’t think if you’re going to be the chief legal officer of New York you should be casual about lumping everybody together. There’s a lot of good people in law enforcement, too, and they’re risking their lives to protect us, and I don’t think it’s a lot to be able to hold those two ideas in your head at once.”

Maloney has polled in second place, behind only labor-backed and Cuomo-endorsed powerhouse Letitia James in a July Siena College poll, albeit with 42 percent undecided in the survey. A New York Times endorsement of fellow Hanover High School alum Zephyr Teachout appears to have increased tension between the two competitors; Teachout took Maloney to task in a Twitter thread, saying “You can’t be the Sheriff of Wall Street if you just handed big banks a massive, early Christmas bonus,” Teachout wrote, referring to Maloney’s vote to roll back certain Dodd-Frank regulations. “And you can’t protect New Yorkers from consumer fraud, predatory lenders, or housing discrimination or if you’re awash in corporate cash,” a reference to the fact that Maloney, like James and Eve, has taken REBNY and real estate donations.

Maloney shot back in the first televised debate between all four primary candidates that Teachout took corporate donations in her 2014 gubernatorial primary run and that many of her private donors work in finance. To his credit, though, Maloney did not offer any criticism of Teachout at Monday’s town hall, saying “Zephyr is a friend,” pointing out that he had endorsed her in the past and saying that Democrats were bruising each other too much in recent elections.

From the law to lawmaking

Born in Quebec, Maloney graduated from the University of Virginia School of Law in 1992 and went into corporate practice, working for Wilkie Farr and Gallagher before eventually transitioning to politics as an advisor in Bill Clinton’s White House in the late 90’s. He ran to be New York’s attorney general for the first time in 2006, running a distant third in the Democratic primary that Andrew Cuomo won. After serving as first deputy secretary for Governor Spitzer and, following his resignation, Governor Paterson, Maloney returned to private practice in 2009. He wouldn’t reach elected office until 2012, when he was voted to the House of Representatives. His recently released tax returns show he still made $10,000 from legal work in 2013, while in office.

While in Congress he has sponsored 35 bills and co-sponsored 431, according to a ProPublica analysis. Of the bills he introduced, three have become law; including legislation to strengthen the FDA’s review process of potentially addictive opioids, and a bill to expand crop insurance for farmers. He serves on the Agriculture and the Transportation and Infrastructure Committees.

Like his competitors for the AG nomination, he has staked his campaign around his opposition to the policies of Donald Trump; to that end he boasts about having a national security clearance and receiving regular updates on the Mueller investigation. Also like his competitors, he has been forced to talk in more detail about more granular New York issues like criminal justice and immigration, in which his record offers a robust but conflicting set of data.

Supports for criminal justice reform, and new protections for cops

Asked about his criminal justice reform plan at the August 27 town hall, Maloney pointed to the Equal Justice Under Law Act, a bill he worked on with Senator Cory Booker, in consultation with public defender and author Bryan Stevenson. The bill sought to expand legal counsel for indigent clients by permitting class-action lawsuits, on Sixth Amendment grounds, in circumstances where legal representation was inadequately funded. The bill was endorsed by the Innocence Project, NAACP and Southern Poverty Law Center. Introduced in 2016 and reintroduced in 2017, the current bill has nine co-sponsors but there’s been little activity since it was re-introduced.

The other criminal justice bills Maloney has sponsored include grant funding for drug diversion and treatment programs, intended to divert low-level drug offenses from jail and prison. And earlier this year he introduced legislation intended to keep better track of all controlled substances sold online.

While he supports scaling back mass incarceration, his support of the Protect and Serve Act suggests a sympathy with narratives presented by police unions, many of which portray police officers as under constant attack.

Maloney voted for the bill in May. It is one of many pieces of so-called “Blue Lives Matter” legislation proposed across the country that would increase penalties for assaulting a police officer, usually by tying it to hate crime statutes. The Protect and Serve Act in Congress would make it a federal crime to assault a police officer, its senate version would classify it as a federal hate crime.

“There are already significant and comprehensive protections at the federal, state and local law level aimed to prevent harm to law-enforcement and to heavily punish anyone who is found to intend or cause harm,” Lumumba Akinwole-Bandele, spokesperson for Communities United For Police Reform, said in a statement to City Limits. “These so called ‘Blue Lives Matter’ bills serve only to advance a false narrative and the dangerous right-wing myth of officers being under constant attack while creating more dangerous conditions for those who are victims and survivors of police brutality,” Akinwole-Bandele added.

An ACLU statement from May by legislative counsel Kanya Bennett shared this criticism; “This bill serves no purpose other than to further dangerous and divisive narratives that there is a ‘war on police,'” it reads. The NAACP, The Leadership Conference and Human Rights Watch released a letter in opposition to the Senate version of the bill.

According to numbers from the National Law Enforcement Memorials Fund, the number of police officers killed in action nationwide has remained more or less at an average of 151 for the past 10 years. This is compared to the 987 civilians killed by police officers in 2017 according to a Washington Post analysis. A study released by the Department of Justice’s community policing division – whose findings had been selectively used by some lawmakers to push the Protect and Serve Act – states:”While concern has grown, all available evidence shows that officer felonious deaths and assaults generally have been declining since the crime wave began subsiding in the latter part of the 1990s.”

Asked about criticism of the bill, Maloney said he disagreed, but expressed a willingness to review those critiques and reevaluate. In defending his vote, he said there is no contradiction between pushing for police accountability and “standing with” police, which he believes is the intent of the legislation.

“Where I live there’s a lot of veterans, a lot of first responders, and I don’t think there’s anything inconsistent,” he said.

Under an executive order by Governor Cuomo in 2015, the New York Attorney General’s responsibilities can, in certain cases, include prosecuting police misconduct.

Asked by City Limits if his stance on the Protect and Serve Act could complicate his performing that duty, Maloney strongly disagreed.

“No, I think to the contrary,” Maloney told City Limits. “I think we have to hold two ideas in our head at once, which is that we want the most professional police force we can have, we want to protect and celebrate the people who make that sacrifice, and we want to hold people accountable for doing it the wrong way.”

More screening for foreign ‘enemies’

In 2015, Congressman Maloney voted for the Securities Against Foreign Enemies, or SAFE Act, a vote that has come under renewed scrutiny in recent months. The bill would have added an FBI background check to the already substantial screening process for refugees from Syria and Iraq.

Forty-seven Democrats voted for the bill, Maloney included, but President Obama promised to veto it at should it reach his desk.

The vote came six days after the Paris attacks that killed 129 people and was viewed by many of its critics as a knee-jerk reaction to that event. The ACLU opposed the bill, saying it would bring refugee admissions from those countries to “a grinding halt.” Then-FBI Director James Comey said that the legislation would make it impossible to admit refugees from those countries into the U.S. Even the U.S. Holocaust Museum put out a statement condemning the bill, drawing an analogy between the plight of Syrian refugees and Jews fleeing Nazi Germany.

CAIR Government Affairs Director Robert McCaw told City Limits, “It was disappointing that he voted for the SAFE act, which would slow down to a near halt the immigration of Syrian and Iraqi refugees,” adding, “we also understood he stood against the Muslim ban and introduced legislation to defund that executive order,” alluding to Maloney’s co-sponsorship of the SOLVE Act. “We would ask that he listen more closely to the Muslim community when making immigration decisions,” McCaw said.

Maloney appeared contrite about the vote in a 2016 interview with the Highlands Current, saying, “I think I blew it on that vote,” but went on to explain his reasoning: a belief that additional screening would have increased trust from the American public and, somehow, pave the way for more refugee admissions. He characterized the vote as one that became polarized by immigration hard-liners and advocates, saying “I think I missed the symbolic meaning to people and I am sorry about that.”

When asked by City Limits about the vote at his town hall, Maloney appeared to defend it: “It would have required the Obama folks to certify the safety of refugees coming into this country, but no additional procedures, and no additional time restraints, and no fewer numbers.” (It’s unclear why the additional background check is not considered a “procedure,” in Maloney’s view.) The bill passed the House but died in the Senate months later.

Going after Israel critics

Maloney, like the majority of Republicans and Democrats in Congress, is a consistent supporter of the state of Israel. To that end he has voted for a bill that goes to controversial lengths, attempting to suppress boycotts by private companies, including small businesses.

The Israel Anti-Boycott Act would create civil penalties at a minimum of $250,000 and a maximum of $1 million to businesses who refuse to do business with Israel on political grounds. Its stated goal is to oppose a UN Human Rights Council resolution on March 14, 2016, which asked companies to divest from the country. The bill was authored by the American Israel Public Affairs Committee and, as first reported by The Intercept, the group had listed it as one of their top lobbying priorities in 2017.

The ACLU roundly denounced the bill in a letter last summer on First Amendment grounds, pointing out that it would issue huge penalties on private citizens for political beliefs.

A flurry of interviews by The Intercept last summer seemed to reveal that many sponsors of the legislation were unaware the criminal penalties the bill allowed, the confusion stemming from the bill’s language, which merely refers back to the criminal penalties of laws it amends.

But Maloney has since offered a full-throated endorsement of the bill and, in an August 22 interview on The Brian Lehrer show, pushed back on a caller who voiced opposition to it, calling boycotts of Israel anti-Semitic.

“I think they’ve got the best human rights record in the Middle East, and we should stand with our friend and ally Israel,” Maloney told the caller. “I’m not going to be party to this BDS nonsense, I think it’s anti-Semitic. I’m really concerned about the radical fringe of the left wing in New York goin’ after Israel. I think that gets you into some really shady and dangerous waters,” he added. (BDS refers to Boycott, Divest and Sanction, the Palestinian-led movement to get individuals and institutions to withhold goods and services from the state of Israel. )

The stance that the Israel Anti-Boycott Act is an anti-discrimination measure is, as the ACLU has pointed out, less than credible, as the Civil Rights Act of 1964 already prevents businesses from discriminating against customers based on religion or national origin, among other things.

Not an ICE abolitionist

Two of Maloney’s competitors in the primary, Teachout and James, have joined nationwide calls by Democrats to abolish Immigration and Customs Enforcement.

Asked by City Limits if he had a stance on this, Maloney did not take issue with the agency’s existence, framing it instead as an entity mishandled by the Trump administration.

Of the call for abolition, Maloney says, “I know what people mean when they say that,” reiterating that story of Martin Martinez, the father of a former staff member who died after being deported. “When people say that, it’s a shorthand for needing dramatic reforms in the way we prioritize how we do enforcement,” he said.

In Maloney’s view, the problem with the agency is that it is guided by federal directives that are too broad, lumping together “terrorists and guys like Martin Martinez, who works at the Office Depot supply warehouse in Middletown and has been here for 30 years, not done anything wrong, but had an unlawful entry misdemeanor on his record from 30 years before.” He believes the agency should instead focus on thwarting MS-13 and terrorists.

ICE’s main role among federal law enforcement dealing with MS-13 is as a deportation force, deployed when authorities fear they will be unable to gain a conviction, either because of the age of the suspect, insufficient evidence, or other reasons, according to congressional testimony by FBI officials. There is no evidence that deportations or ICE raids have lead to a decrease in the size of MS-13, a a gang formed by deportees. There is, however, some evidence that a strategy of mass deportation has made the gang stronger by spreading it across Central America.

The Martinez family told Roll Call earlier this month that Martin Martinez received his deportation order in 2007, after an appeal for an asylum application had been denied. The elder Martinez was first detained by ICE in 2013, under the Obama administration, as a result of two separate DUI convictions from 1996 and 2001, the family told Roll Call. He was able to stay in the country for years through a stay of removal while exhausting all legal options, but was finally deported in 2017, after deportation priorities were broadened by a Trump executive order.

While it’s likely that the nativist turn of the federal administration and accompanying executive orders played a part in Martinez’s hurried deportation, the situation as presented by the Martinez family suggests that he could have still been deported under Bush- and Obama-era policies. In other words, if the Martinez situation is a result of executive misuse of ICE, that misuse essentially dates back to the agency’s 2002 creation.

Getting ‘lit up’

In the nearly-hour long August 27 town hall, Maloney spoke on a range of other issues, from cybersecurity and social media (“Social media is like the new tobacco: We thought for a while that all the cool kids did it, and now we’re all hip to it and it’s killing us”) to recent public-housing controversies (“if we had private landlords running their facilities like NYCHA they’d be in jail”).

He has been quick to point out that he’s the only candidate in the attorney general primary who is doing town halls – a quick look at his competitors’ campaign websites seems to confirm this. Whatever his views, it would be hard to deny that Maloney is the candidate who most enjoys meeting people, as his ambitious town hall spree attests – he did 30 in 30 days for this AG run.

Like his competitors, Maloney wants to be viewed as a fighter, eager to take on the Trump administration, and in one ad evoked intense imagery to this end. In Maloney’s most talked-about TV spot, he asks us to imagine him standing in his home with a baseball bat, guarding his loved ones from intruders. But his positions portray a murkier strategy more focused on generating broad support. And those views may be more suited for the general election, as Maloney has suggested: 38 percent of New York State voters went with Trump in 2016.

Maloney says he’s criticized by both sides. When one town hall attendee said she was disappointed on a vote against some parts of the Affordable Care Act, he said “I’m constantly getting lit up,” for being too close to the left wing of the party. Whether Democratic primary voters agree is still unclear.

One thought on “Maloney Running on a Complex Congressional Record”

What is Zephyr Teachout’s stance on BDS?

This is important to me and many others.

A quick response would be appreciated, as I plan to vote before the polls close this evening.