Willis Elkins

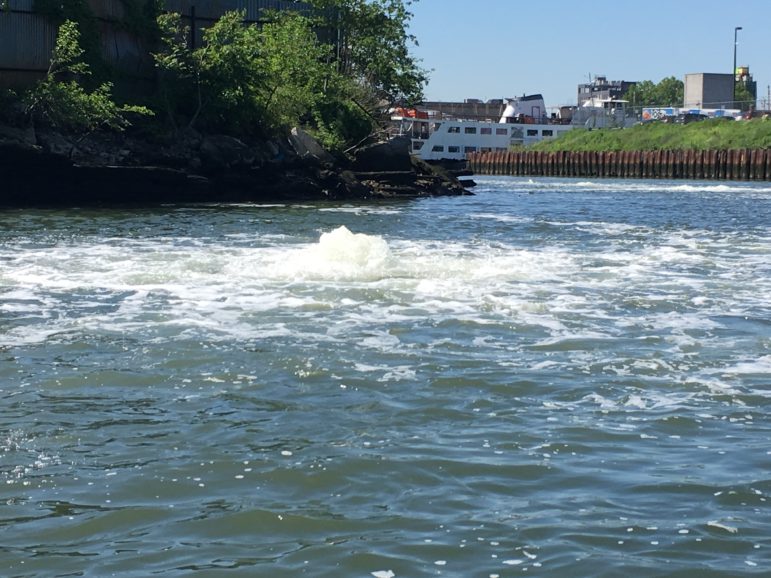

The aeration system at work in Newtown Creek. Its aim is to oxygenate waters to support fish life.

New York City has just begun pumping oxygen into a second section of Newtown Creek in Greenpoint, but critics say the city’s methods to increase oxygen levels may be hazardous to the public’s health.

Newtown Creek, the East River tributary that separates Brooklyn and Queens, was designated a federal superfund site in 2010 following a history of industrial use, a decades-long oil spill and the ongoing discharge of excess raw sewage from the city’s sewer system during times of heavy rain and snow.

That year, the city installed an aeration system, designed to pump oxygen directly into the murky waters of the English Kills section of the creek near East Williamsburg, to meet a consent order from the New York State Department of Environmental Conservation. The federal Clean Water Act requires bodies of water to meet certain oxygen levels in order to help maintain aquatic life.

This spring, the New York City Department of Environmental Preservation installed a second system, located in the East Branch of the creek. The DEP brought that second section online this summer.

A 2012 study found that the oxygen-pumping process at the English Kills branch was spraying bacteria directly into the air. The study said that bacteria from the creek was being aerosolized – or being turned into a fine spray – when bubbles burst in the water. Once aerosolized, wind can transport the bacteria over land.

The aeration system also breaks down frequently, causing water to bubble up one to two feet over the surface of the creek, according to critics.

“It’s like a constant exercise in failure,” Mike Dulong, a senior attorney at the environmental organization Riverkeeper, said. “We’re not confident that this is good policy.”

The DEP evaluated those concerns in 2012 and found that aeration posed no health risks.

Members of Newtown Creek Alliance, a local advocacy group, monitor both systems, said Willis Elkins, the organization’s program manager. Last year, the English Kills machinery was broken 19 out of the 19 times they checked it, and this year isn’t faring any better, he said.

The new East Branch section has already broken in two different locations, Elkins said.

The DEP said it monitors the system and makes repairs as needed, but wouldn’t confirm how frequently the machinery breaks.

The NCA also collects water samples and tests them through a partnership with LaGuardia Community College. Last year their data showed that oxygen levels in the East Branch met federal requirements the majority of the time, without aeration.

“What we want to do is have the city and the state put greater effort into examining where the real needs are,” he said. “There should be a mechanism for studying oxygen, and the system should respond to that – not just treat the creek, as if it needs aeration six months out of the year.”

For the areas of the creek that do suffer from low oxygen levels, Elkins said, there are alternatives to aeration. Natural vegetation such as spartina grasses, as well as ribbed mussels that grow near their roots, can help remove unhealthy nutrients that cause algae blooms and help increase oxygen levels. He also compared an aeration system that was temporarily installed in the Gowanus Canal which, by design, did not send oxygen above the surface of the water.

There is also an aeration system installed in Shellbank Basin in Queens, according to the DEC.

Activists want to study possible chemical compounds that might be released into the air as well.

They look to a 1992 New York City Health Department survey, done in response to concerns over the area’s toxic history, that found that residents of Greenpoint and Williamsburg had higher rates of stomach cancer and some kinds of leukemia than New Yorkers in other neighborhoods. That spurred residents to push for a more comprehensive review, but in 2016, the New York State Health Department published a study that found no elevated rates of birth defects or cancer in residents near Newtown Creek.

The Environmental Protection Agency is not involved in the management of the aeration systems, the federal agency said. The EPA did say that instream aeration is regularly considered by local officials and engineers to address bodies of water with low oxygen levels, but the agency does not track how aeration is used around the United States.

Ultimately, the city needs to reduce the sewage overflow in the creek, Elkins said.

The DEP has taken steps to mitigate the overflow. That includes such measures as planting local gardens that are designed to soak up rainwater and building other infrastructure that redirects the flow of water.

The DEC said the city has plans to build a massive $1.4 billion sewage storage tunnel that will reduce overflow by about 62 percent.

“I think DEP does want to find a solution that satisfies its needs and addresses some of our concerns,” Elkins said. “In Dutch Kills, they are in the middle of doing a big wetland expansion, which is exciting. But part of the problem is they’re locked into this thing they’ve already built.”

Brad Kerr, a Greenpoint resident and a member of the North Brooklyn Boat Club, said the members of the group take precautions to avoid contact with the water while paddling or canoeing. Recreationalists also avoid going too close to the aeration system.

Kerr said passers-by who are unaware of what the aeration system is often think a water main has broken or that the water just looks “gross,” because of the bubbling.

“It’s a little counterintuitive for the city to be making Newtown Creek look creepy as part of its responsibility to make Newtown Creek fishable and swimmable,” he said. “Those words can’t just mean a certain bacteria count. That has to mean making Newtown Creek a place where you might want to fish or might want to swim or walk over the Creek without saying, ‘Something’s wrong here.’

“And that’s what they’re doing – making the Creek repellant to people who live near it and might want to use it.”