Adi Talwar

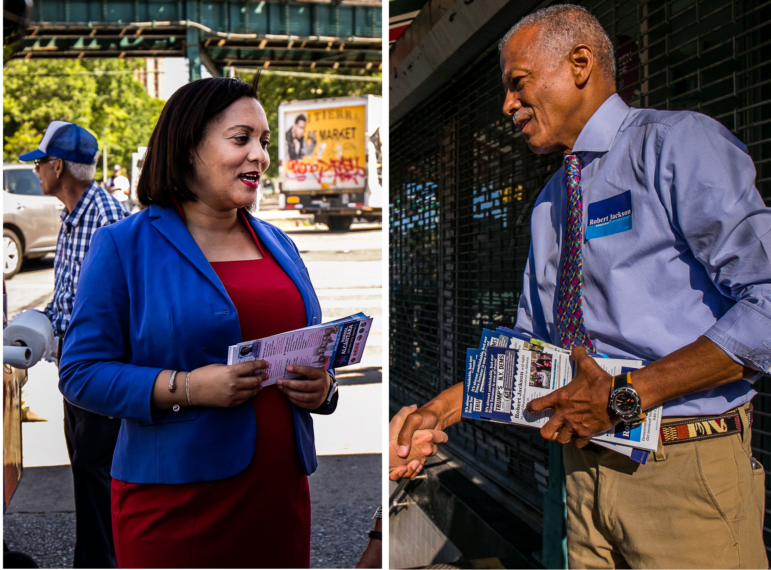

On a recent Thursday afternoon in the Inwood section of Manhattan, New York State Senator Marisol Alcantara canvassing at the intersection of Nagle Avenue and Dyckman Street.

On paper, there is little difference between Marisol Alcantara and Robert Jackson. They are both progressive Democrats from northern Manhattan with roots in the labor movement. Both have played David in the fight against different Goliaths—Jackson as the lead plaintiff in the Campaign for Fiscal Equity lawsuit that found New York State was shortchanging city schools, Alcantara as an insurgent candidate shunned by her own brethren who somehow defeated an 18-year incumbent to become the first Latino district leader in West Harlem seven years ago.

The key difference is that when they ran in a primary for the 31st State Senate district two years ago, vying for the seat vacated by Adriano Espaillat heading to Congress, Jackson took a pledge to caucus with the mainline Democrats if he won. Alcantara did not. Instead she was the beneficiary of nearly $540,000 from the campaign finance entity operated by Independent Democratic Conference leader Sen. Jeff Klein.

Alcantara prevailed in that September 2016 primary with 32 percent of the vote. Former Bloomberg administration member Micah Lasher claimed 31 percent and Jackson 30 percent. Alcantara was formally elected the day Donald Trump won the presidency and, as part of the IDC, supported Republican control of the state Senate from her first day in office until the reunification of the Democrats this spring.

Hear Them Here

Both candidates appeared on the Max & Murphy show on August 1st.

Click to listen.

Now Alcantara finds herself as perhaps the most vulnerable former member of the IDC facing a primary on September 13. Jackson has endorsements from a long roster of public officials (including two members of Congress), a litany of political clubs, some labor organizations and a who’s who of progressive advocacy groups.

And with a court having declared the IDC’s campaign-finance mechanism illegal, and the state’s top campaign-finance enforcement officer looking to return that money to donors, Alcantara faces the threat of a mortal blow to her finances just before the election.

Jackson believes he has political momentum and electoral math on his side. “Two years ago there were four of us in the race. Donald Trump was not president. You have all of these 60 groups that have risen up since Donald Trump became president that are extremely actively involved” and, he notes, are backing him. Plus, 68 percent of the vote in 2016 went to people not named Marisol Alcantara, and Jackson believes he will claim the overwhelming majority of people who supported him and Lasher in that race. “So when you look at that, all in all, we win.”

Alcantara doesn’t deny that she faces long odds. What she does dispute is that she deserves to be judged solely for her membership in the IDC.

“I just think it’s interesting that people who are my opponents are trying to wipe out my entire career of work—in the labor movement, for immigrants, and on behalf of women’s issues—because of a year and a half that I spent in the IDC,” she says. “My opponent doesn’t talk about anything that I’ve voted on. Everything my opponent is campaigning on is: I was a member of the IDC.”

Achievements and failures

Alcantara is not friendless. Senate Minority Leader Andrea Stewart-Cousins is backing her, as are several unions, like 1199 SEIU, DC 37 and the New York State Nurses Association, where she used to work as an organizer.

Before her time with the nurses, Alcantara—who emigrated from the Dominican Republic when she was 12 and grew up outside of Washington, D.C.—worked for an organization called Immigrant Workers Action Alliance that aimed to help service-sector employees affected by the September 2001 terrorist attacks, organized Latino voters in Florida in the 2004 presidential election, and was part of Rev. Al Sharpton’s National Action Network.

Her 2018 campaign platform sounds right in step with that progressive backstory. She lists as her campaign priorities the Dream Act, reproductive rights, speedy trial, an end to cash bail, early voting, repealing vacancy decontrol, a ban on coastal drilling, tighter gun control and public campaign financing.

The question is whether her joining the IDC was in step with those principles. The deal between the GOP and Klein’s coalition was that the breakaway Democrats assented to Republican control of the chamber (which depended chiefly on Brooklyn Democratic Sen. Simcha Felder’s decision to caucus with the GOP) in exchange for getting action on its bills.

Well, some of its bills. Alcantara has passed a dozen pieces of legislation since taking office in early 2017, and her office says other proposals of hers have been incorporated into the state budget instead of law. One law compelled the state Division of Homes and Community Renewal to add to its standard rent-stabilized lease rider new language informing tenants about what non-rental fees landlords are allowed to charge. Others mandated a study of emergency alert notification systems and created advisory panels on employee-owned businesses and adolescent suicide prevention. She was also the sponsor on two bills that expanded contracting opportunities for minority and women-owned businesses in New York City.

But none of those laws address the core progressive agenda Alcantara has articulated. Rent reform has gone nowhere. Another case in point is the Farmworkers Fair Labor Practices Act, which would rectify inequities in state labor laws that exempt farm laborers from key protections. The Assembly has passed the law again and again. In the Senate, Espaillat—Alcantara’s predecessor—tried and failed to get the bill passed for six years. Alcantara picked up the mantel, reintroducing the bill in January 2017. It got a hearing a year later, passed the Labor Committee she heads, and now lies fallow in the agriculture committee.

“I was very disappointed in the farmworkers’ bill. I worked very hard at building coalitions with senators on both sides of the aisle,” she says. Yet she is quick to contextualize that failure. “The farmworkers’ bill has been around for 20 years. The Democrats were in control of the Senate in 2009, and nothing happened to the farmworkers bill.”

To Jackson, this demise of the farmworkers’ measure just strengthens the indictment of Alcantara’s decision to join the IDC: What was the purpose of giving Republicans a larger governing majority if meaningful legislation went nowhere?

“She knows that many of these things that she has signed on to, which have passed the Assembly but the state Senate has not even had a hearing or not passed it, they’re not going to be done. And the reason they’re not going to be done is the IDC and Sen. Simcha Felder have basically given control of the State Senate to the Republicans and to John Flanagan. [Alcantara] knows it. The activists know it.” He gets particularly incensed talking about the episode in March 2017, when Democrats tried to get school funding attached to a Republican bill. A vote was called on that amendment. A show of hands was demanded. Faced with a choice between voting against school funding or voting against their Republican allies, the IDC simply walked out of the chamber. “That’s the sham — sham! — being played on the people we represent,” Jackson says.

Alcantara points with pride to other kinds of success: Namely, getting state money for the district. Her campaign website lists funding for after-school programs, $1 million for CUNY in the Heights, $150,000 for tenant legal services, hundreds of thousands for local schools, and money for suicide prevention, among other recipients.

The senator believes she has brought vital resources to a district “that had been an afterthought.” Jackson counters that “eating crumbs off a Republican plate like a rat” is small consolation when people are being evicted from homes or deported from the country with implicit approval by the Republican majority.

Degrees of discomfort

Asked if working with the Republicans in the era of Trump made her uncomfortable, Alcantara is somewhat evasive. “I was proud of that work that I did. I’m proud that I was able to pass 12 bills. Uncomfortable?” She pauses. “When you look at the makeup of the Senate, you know, I am a woman of color. I am an immigrant. I am always in places where I feel uncomfortable, even among people who are ‘Democrats.’ When you are a person of color in the city, and you bring up issues that are important to you, you’re always uncomfortable because even amongst your progressive friends, they always accuse you of pulling the race card, of making everything a racial issue.”

This comes up often on the campaign trail, she says. “If you see the way I’m treated on one side of Broadway, it’s very different from how I am treated on the other side of Broadway.”

(The IDC, of course, started as an all-white quartet, before adding and losing Malcolm Smith and then enrolling Jose Peralta of Queens, Alcantara and Jesse Hamilton of Brooklyn. Before the unity deal made them all one big happy family again, Alcantara accused mainline Democrats who criticized her as embodying white privilege; they retorted that their conference—unlike the IDC—was led by a woman of color.)

In Alcantara’s telling, it was the establishment’s dismissal of her that led to her attachment to the IDC in the first place. She jumped into the race to replace Espaillat rather late and, “When I reached out to folks that I thought would have been natural allies or that would have been interested in backing a woman, a Latina, an immigrant for the seat, they were not interested in backing me,” she says. “There were people who didn’t even meet with me, didn’t give me the time of day.” Councilmember Ydanis Rodriguez and Espaillat were her only local allies. “The entire establishment was against me.” But Diane Savino, the Staten Island senator who was one of the founding members of the IDC, also reached out. “And to be honest, only the IDC showed an interest at changing the dynamic of the NYS Senate”—in other words, adding a Latina voice.

Alcantara believes this dynamic is again in play in her race against Jackson. “I find it interesting that most of the elected officials in Jeff Klein’s district, in Diane Savino’s district, in [Sen. David] Carlucci’s, in Tony Avella’s district are supporting them for reelection, but that same thing didn’t happen to me. I think that a lot of my colleagues are specifically targeting me.”

Why? “I think I’m the only woman that they’re targeting. I’m the only woman of color,” she says. “I visit all these clubs that are supporting [Lt. Gov.] Kathy Hochul, that are big fans of [Sen. Kirsten] Gilibrand, when Kathy Hochul [opted] to not give driver’s licenses to undocumented workers and when Gillibrand was a pro-gun Congresswoman. So all these progressives that are like targeting me because of a year and half that I joined the IDC … they have decided to erase my record of being a Bernie Sanders delegate, of being a trade unionist, of all the work that I have done in this community.”

In fact, several top pols—including Comptroller Scott Stringer and Council Speaker Corey Johnson—have endorsed Alessandra Biaggi, the Democratic challenger to Klein, and elected officials have also sided with some of the other challengers to the ex-IDCers. But there’s no question that a heavier slate of establishment names is behind Jackson than any of the other ex-IDC opponents.

Still, endorsements only carry so much value. The real lifeblood of a campaign is money. Jackson has a slight funding advantage over Alcantara, with $158,000 in the bank as of July 15 compared to her $107,000 – that in spite of the fact that the Senate Independence Campaign Committee has funneled $170,000 to Alcantara so far this year. She could be forced to return some of that money, as well as money she received from that entity in 2016 – and claims she is prepared for that. “I am willing to abide by whatever decision that judge makes in regards to if we have to return the money.”

A runner and a fighter

Adi Talwar

Robert Jackson canvassing at the Isham street entrance of the A train station. Two years after a narrow third-place finish, he believes the math is on his side this time.

This will be the 12th time that some northern Manhattan voters will have the chance to vote for Jackson. He won a five-way Council primary in 2001 with 30 percent of the vote, cruised in the general, and easily won primaries and general elections to retain the seat in 2003, 2005 and 2009. But his attempts at higher office have fallen short. He placed third with 19 percent in a crowded Democratic primary for Manhattan borough president in 2013. Less than a year later he announced a challenge to Espaillat, who decided to seek re-election to his Senate seat after losing a Congressional primary to Charlie Rangel for the second cycle in a row. Jackson lost that race fairly narrowly, 47-40.

Two years later, Rangel retired, Espaillat was moving to Washington in his place, and Jackson, Alcantara and Lasher battled to replace Espaillat. A minor candidate named Luis Tejada took five percent of the vote. Alcantara, Lasher and Jackson split the rest more or evenly: Only 533 votes separated the winner, Alcantara, and Jackson in third place.

Jackson’s policy platform this time is substantially more detailed than Alcantara’s. On education, he wants to “assign effective teachers to ‘high needs’ schools with additional pay and other supports designed to improve both instruction and outcomes” and “increase awareness and training on dyslexia, its warning signs and appropriate intervention strategies.” Among other things, his electoral reform wishlist includes “a truly independent redistricting Commission with the goal of ending partisan gerrymandering.” He calls for ending vacancy decontrol in rent-stabilized housing and also repealing the Urstadt Law that gives the Senate power over the city’s rent laws in the first place.

Bespectacled and lean, Jackson is a long-distance runner by hobby—he’s ignored injuries on the way to finishing marathons and once walked to Albany to bring attention to education inequality. But he’s a middleweight fighter by disposition. As a Councilmember he led the Education Committee and often confronted Bloomberg-era DOE officials, his voice rising, insistent. Sometimes Jackson’s intensity has created awkward moments – like in 2013, when mayoral candidate Bill Thompson failed to acknowledge him at an event and Jackson shouted, “Hello? Am I black enough for you, brother?” or in 2016 when he told NY1 Noticias, “I say loud and clear to anyone who is viewing this and beyond: You don’t have to be Latino, you don’t need to be Dominican to best represent the district…because quite frankly, there have been Dominicans that have been representing Dominican districts that are going to prison. So don’t tell me they were good representatives.” Some Dominican-American pols found the comments offensive.

As a Councilmember, Jackson supported Bloomberg’s bid to overturn term limits, citing his own long-time opposition to them. He backed congestion pricing, but resisted the Bloomberg ban on massive sodas, citing the impact on small businesses—a longstanding area of concern for him.

It was ostensibly with small businesses in mind that he and the Black, Latino and Asian Caucus (which he co-led) also opposed Bloomberg’s ban on foam containers. It was Jackson’s amendment to the foam ban—which called for a study of whether foam could be recycled—that led to years of delay implementing the ban, much to the delight of the Restaurant Action Alliance. When Jackson ran for Manhattan borough president, the Restaurant Action Alliance spent $13,000 on a mailer for him – the only spending the organization did, an independent expenditure beyond Jackson’s control.

By 2015, Jackson was the president of the Restaurant Action Alliance. In the capacity, he testified at one point in favor of making it easier for businesses to escape the ban, arguing, “any avoidable harm to a small business’s bottom line causes that business owner undue financial hardship” – a sweeping statement that could be hard to reconcile with some progressive positions regulating businesses.

Asked if that move from Council ally to paid associate was “icky,” Jackson says, “I don’t think it looks icky because the position of the caucus was this would hurt small business. I was out of the Council and they approached me.”

And after September?

While the contest between Alcantara or Jackson will be decided on September 13, its impact won’t be clear until after the general election, which will decide whether the Senate remains in nominal Republican control (thanks to Felder caucusing with them) or if the Democrats finally break through.

“The goal and objective is to elect Democrats – more than the 32 that area needed,” says Jackson. “We need 34, 35 so that one individual –Simcha Felder or someone else, it doesn’t matter — can hold up the situation.”

Alcantara, however, is skeptical that even a Democratic majority can deliver the profound changes that progressives seek. “We need to understand that there are Democrats that come from rural or suburban districts, that their needs and their politics and their views of social issues are not the same as someone from the Upper West Side.”

“You know, we have some colleagues that might not be supportive of sanctuary state. We have some of our colleagues that are not supportive of drivers’ licenses for undocumented workers. You have some members of our conference who are probably not going to be supportive of ending solitary confinement,” she continues. “And that’s a reality that the leadership of our party is going to have to deal with.”

13 thoughts on “Meaning of the IDC Looms Large in Alcantara-Jackson Senate Rematch”

Ms. Alcantara might have a progressive past, but her first term in Albany has proven her to be too safe in her actions. Why didn’t she support the Child Victims Act or the Reproductive Health Act – two important bills that have been ready to vote on for years? She seems to be saying that she has to follow the agenda of more conservative, upstate Democrats. But I have an issue with that. First, her predecessor was too conservative for this borough as well, and would have been voted out had he stuck around. I’m under the impression that Espaillat practically handed her the job (and a tougher battle in 2018). And second, how can you act like a conservative, upstate Democrat in this borough? We have a new paradigm in the age of an imploding GOP – be progressive or be voted out.

Refreshing to know that she is not a cookie-cutter progressive whose only skill is to read off the bullet points given to her by their political masters.

Robert Jackson is a profesional politician whose only job outside of politics is politics. Never done anything for the people east of Broadway, folks who seem to treat us as third class citizens.

It’s all too appropriate that the senator says “they always accuse you of pulling the race card, of making everything a racial issue” and then immediately pivots to a racial dog whistle about “how I am treated on the other side of Broadway”. Anyone that lives in the neighborhood knows which group of people she is talking about.

Since the moment that I read about the racist remarks on the Senate floor directed at Senator Gianaris by Senator Alcantara, I knew that I would be voting for her opponent, whoever he/she would be.

Why would anyone want someone representing them who is prejudiced against their race?

Robert Jackson was an enabler of Chris Quinn’s non progressive legislative. he voted to overturn term limits against the will of the people. he has no compassion for animals. he was disrespectful to activists in the city council. he sold out the neighborhood to Columbia university. no wonder he had all the whites supporting him. he displaced all the people of color with his alliance with slum landlord. shame on these progressive for their silence on Jackson notorious record in the city council

he does give a damn about ur kids. it is all about more money for the uft to spend while your kids remain uneducated. never once did he ask for educational reforms. Jackson is the corporatist machine backed career politician

You know Alcantara was endorsed by the UFT, right?

Pingback: Max & Murphy: Democratic Senate Rivals Point to Results, Republicans and Race – USA Current News

Pingback: – NYS Primaries: Alcantara vs. Jackson

Robert Jackson ran one of the worst district offices when he was a council member. High turnover, he treated staff like crap. Then he ran for Manhattan Borough President…oh oh that’s not on his bio??? why?? Now, this is the 2nd time for his to run for Senate. Couldn’t they find someone else to run?

I am learning about both candidates for the first time and hear both positives and negatives that leave me on the fence. I like Ms. Alcantara’s progressive background and her willingness to join ‘the IDC to get things accomplished. But indeed it sounds like her strategy has not been particularly effective, she isn’t owning up to it and seems too pessimistic about the potential of a blue wave to really move the ball forward. I believe we should give representatives more than 2 years to make their mark, but would feel more comfortable hearing Ms Alcantara talk about her agenda to work with the Dem’s this time around.

As far as Mr Jackson goes, I like the fact that he speaks his mind. But as someone who believes it is our responsibility to address society’s health and environmental impacts for the sake of our children, i cannot support Mr. Jackson’s rejection of the soda and foam ban with the excuse of protecting small business. It is the job of even small businesses to adapt their offers to better serve their public. I want a representative that is protecting that same public.

Both of these candidates are unacceptable.If it didn’t divide the resulting votes into thirds we should have an alternative candidate.

This article neglected to mention that there are two other candidates in the race, which I regret

Tirso Santiago Pina (his website, which was exclusively in Spanish, does not appear to be functioning

Thomas A. Leon has this Facebook page: https://www.facebook.com/ThomasAlbertoleon

“We need to understand that there are Democrats that come from rural or suburban districts, that their needs and their politics and their views of social issues are not the same as someone from the Upper West Side.”

That’s the problem. Not only has Ms. Alacantra forgotten she was supposed to represent Democrats, she also seems to have forgotten that she represents the the Upper West Side Democrats who elected her, not rural or suburban districts.