Adi Talwar

Dulcie Canton was biking through Bushwick when she was struck in August, 2014. The driver never stopped. She was hospitalized for three days with brain trauma and a broken shoulder.

Last month, New York City officials announced that 2017 saw the fewest pedestrian deaths since record-keeping started in 1910.

According to a statement released by the mayor’s office, pedestrian fatalities have dropped by 45 percent since 2013, the year before Vision Zero launched.

Projects like fixing Queens’ infamous ‘Boulevard of Death’ have contributed to their steep decline.

“Vision Zero is working,” said Mayor Bill de Blasio. “The lower speed limit, increased enforcement and safer street designs are all building on each other to keep New Yorkers safe.”

But what the mayor’s numbers don’t show is that New York City has suffered from a hit-and-run epidemic for years, and the NYPD is struggling to keep up.

In the past five years, the number of hit-and-runs in New York City has increased 26 percent, from roughly 36,000 incidents in 2013 to 46,000 in 2017, according to NYPD data.

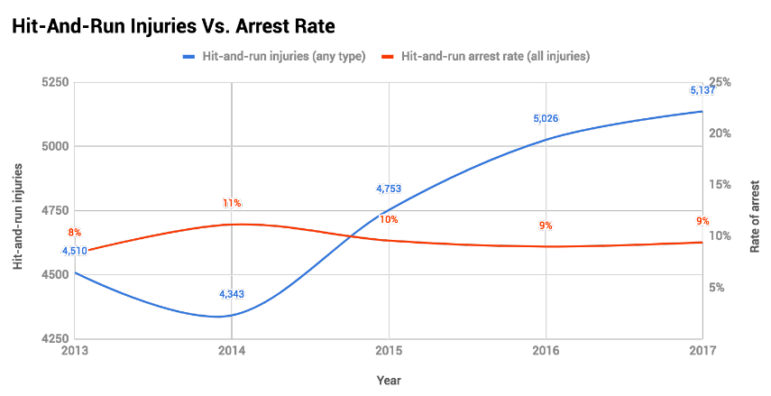

Most of those crashes involve damage to property, not people. But in 2017, more than 5,000 hit-and-runs resulted in injury, a 14 percent increase since 2013. At least one person was killed in a hit-and-run crash each week in 2017, according to figures cited by the New York City Council.

But even more surprising is how few of these crashes result in arrest.

Overall, police are only making arrests in about 1 percent of all hit-and-run crashes each year, a rate that has not budged since 2013. Summonses are issued in some of the cases involving only property damage, but still only in about 1 percent of such cases.

Last year, only 9 percent of hit-and-run drivers who injured someone in New York City were arrested, according to NYPD data.

Even in the most serious cases, the majority of hit-and-run drivers see no consequences. In 2017, only 24 of the 62 hit-and-runs that resulted in critical injury or death led to arrest.

The City Council took note last year by introducing an alert system that notifies residents of hit-and-runs via phone, radio, and television broadcasts. The system’s goal is to facilitate police arrests by immediately involving the community in a search.

But the problem runs much deeper than just catching drivers on the run.

Advocates say that, over the years, insufficient investigative resources, a toxic culture of victim-blaming, and a loophole in state traffic law have allowed hit-and-run drivers to slip through the cracks.

Treading water

The problem begins with the Collision Investigation Squad (CIS), a unit of the NYPD’s Highway Division that specializes in crash investigations.

In 2013, the NYPD revamped the CIS, boosting it with ten additional detectives and high-tech tools. The reform came after City Councilmembers criticized the unit’s handling of two deadly crashes in Brooklyn in 2011, one of which was a hit-and-run.

G. Le Dem

The NYPD dropped the word “accident” from the unit’s name, opting for “collision” instead to avoid “the inaccurate impression or connotation that there is no fault or liability associated with a specific event.”

Furthermore, police Commissioner Raymond Kelly announced the CIS would start investigating crashes that involved “critical” injuries, expanding their scope beyond just fatal crashes.

“I expect there to be an increased number of collisions that will be investigated,” wrote Kelly in a letter to the chairman of the Council’s Transportation Committee. “A critically injured patient will be defined as either receiving CPR, in respiratory arrest, or requiring and receiving life sustaining ventilator / circulatory support.”

But five years down the road, the NYPD is still just treading water, overwhelmed by a steady increase in hit-and-runs that shows no sign of abating.

Although the CIS investigated 30 percent more crashes in 2017 than it did in 2013, the arrest rate for hit-and-runs that result in “critical” injury or death has actually decreased in the last two years, going from 47 percent in 2016 to 39 percent in 2017.

‘Critical’ cut-off

With just 21 detectives, 3 police officers and 5 supervisors, the Collision Investigation Squad cannot respond to the hundreds of crashes that occur daily in New York City. CIS is only called to investigate if someone is killed or if emergency responders determine that a victim is “critical.”

But the term has raised eyebrows, as its narrow definition precludes many serious injury crashes from being thoroughly investigated and prosecuted. Safety advocates say its use may violate state law, which requires police to investigate “whenever a motor vehicle accident results in serious physical injury or death to a person.” (Section 603-a)

Most police departments in the state of New York stick to “serious injury”–a much broader term–to determine whether a specialized unit will investigative a crash.

Furthermore, district attorneys are reluctant to charge a hit-and-run driver unless the CIS was involved in the crash investigation. Advocates say this prevents victims who were not deemed “critical”, but may have suffered life changing injuries, from getting justice.

“There is a question of whether the NYPD is even adhering to its obligations under state law,” said Marco Conner, the Legislative and Legal Director at Transportation Alternatives, a non-profit advocating for the safety of pedestrians and cyclists in New York City.

“By not responding to thousands of serious injury cases [the CIS is] cutting off the possibility of bringing criminal charges,” said Conner.

Troubled investigations

When crashes involve injuries that are anything less than “critical”, they are handed down to NYPD precinct detectives.

But unlike CIS detectives, precinct detectives are not extensively trained in crash reconstruction.

Testimonies from several victims, lawyers, and advocates suggest that many hit-and-run investigations declined by the CIS are poorly handled and even swept under the rug.

Lindsay Motlin was hit by a van near the Grand Street “L” station in Brooklyn, on December 15, 2013. She suffered a broken skull, lacerated spleen, and fractures to her shoulder, tibia, pelvis, tailbone, and hand.

Her injuries were not deemed critical, so the 90th police precinct picked up her case.

“It took four of five calls before I got in touch with the detective on my case,” said Motlin.

A month after the crash, Detective Paredes closed her investigation for lack of evidence, stating that no cameras or witnesses had been found.

Police records later obtained by Motlin through a Freedom of Information Act request stated that Detective Paredes had interviewed Motlin days after the crash, and that she had failed to identify the vehicle that hit her.

But Motlin said the interview was a complete fabrication. She was undergoing surgery at the time stated in the records, she said.

“It felt like everybody gave up,” she said. “To me, it’s a huge lost opportunity. It probably could have been figured out.”

Motlin said her injuries cost her thousands of dollars and forced her to quit a consulting gig that required frequent travel. She is no longer able to run and will eventually need knee-replacement surgery.

Bernadette Pietrefesa, a 51-year-old flight attendant, was also dismayed by the way police handled the investigation into her crash, she said.

Pietrefesa was heading to the airport early on the morning of June 8, 2016, when a hit-and-run driver struck her at the busy intersection of Third Avenue and 41st street in Manhattan.

The vehicle dragged her 50 feet from the crosswalk, where she was crossing with the signal, she said.

Pietrefesa was knocked unconscious and transported to Belleview Hospital, where she was intubated with serious injuries. After undergoing chest replating surgery, she remained hospitalized for 10 days with fractures to her back, knee, and foot, and severe abrasions that took six months to heal.

On the day after the crash, Detective Christopher Kolenda of the 17th precinct got Pietrefesa’s account of the crash at the hospital. It was the last time she saw or spoke to the detective, she said.

Pietrefesa said her lawyer, Stephen Fry, struggled to reach the detective before learning that police had partially identified the driver’s license plate. Weeks later, police told Fry they had paid a visit to the home of the vehicle’s owner, who refused to talk.

The investigation was closed and no charges were brought for lack of evidence.

Pietrefesa says her lawyer later learned the detective had taken a two-week vacation in the early stages of the investigation, and had retired soon afterwards.

Pietrefesa filed a FOIL request for police records pertaining to her crash in July 2016, but has yet to receive the documents.

“I had complete faith in the justice system,” she said. “I believed they would find the person. There are cameras everywhere–it’s 41st and Third Avenue in Manhattan.”

Due to her lingering injuries and the physical nature of her job, Pietrefesa has not been able to return to work as a flight attendant for American Airlines.

Neither the NYPD nor the Detectives Endowment Association, the union representing NYPD detectives, responded to a request for comment about the specific cases cited here.

DIY detectives

Hit-and-run victims frustrated by the police’s inaction sometimes resort to hiring private detectives to investigate their crashes. But even with all the right evidence, getting justice is nearly impossible.

Dulcie Canton was biking through Bushwick when she was struck at the intersection of Wilson St and Bleeker Ave, on August 7, 2014. The driver never stopped.

She was hospitalized for three days with brain trauma and a broken shoulder at Wyckoff Heights Medical Center.

Hours after the crash, Canton’s friend collected evidence at the scene with Steve Vaccaro, one of New York’s best-known traffic lawyers.

Security footage and a piece of a side-view mirror allowed them to identify the vehicle’s license plate and model, and subsequently, the vehicle owner’s name and address. The next day, they spotted the Chevy Camaro near the scene of the crash.

The evidence was passed on to the 83rd precinct, but Vaccaro says that weeks went by before police followed up. He was told the detective assigned to the case was on vacation. Later on, Detective Tallarine repeatedly said he was busy solving a murder, Vaccaro said.

“They don’t see it as a crime,” said Canton, referring to the NYPD. “They see it as civil. Let them hash it out with the insurance and that’s it.”

Vaccaro and Canton voiced their frustration at a community policing event, but the NYPD shrugged off their concerns and accused them of hindering the investigation by talking to the press.

Canton is now a full-time employee at Transportation Alternatives, a cycling and pedestrian safety advocacy group based in Manhattan.

She said the issue is fueled by a culture that does not hold drivers accountable for their actions.

“Driving is seen as a right and not a privilege,” Canton said. “You know, get your car, do whatever.”

An incentive to flee

The lack of accountability for hit-and-run drivers is compounded by a legal loophole that gives intoxicated drivers an incentive to flee.

In New York, killing a person while driving drunk is a class C felony punishable by a maximum of 15 years in prison. But fleeing the scene of a deadly crash–a class-D felony–carries a much lower sentence of up to seven years in prison.

Fleeing buys intoxicated drivers enough time to get sober, thus allowing them to elude longer prison sentences, said Dan Flanzig, a lawyer for hit-and-run victims in New York

Early last year, State Senator Marty Golden proposed to increase hit-and-run penalties by amending Section 600 of New York’s Vehicle and Traffic Law, but the bill never made it out of Transportation Committee.

“The problem is that I don’t see enough enforcement of this law as is,” said Flanzig.

“My fear is that increased penalties won’t be enough to motivate police and district attorneys to enforce the law and prosecute those who violate it.”

Lack of transparency cited

Because criminal charges against hit-and-run drivers are rare, many crashes are resolved in civil court.

To obtain a settlement, it is vital for victims to have the right evidence. But safety advocates complain that the NYPD is reluctant to disclose police reports.

“Every two hours a driver in New York City leaves an injured victim behind in a hit-and-run crash,” said Marco Conner from Transportation Alternatives.

“These victims deserve the absolute best evidence available to support their case for relief, and as a city we must have transparent and comprehensive public NYPD data to deter these heartless hit-and-runs.”

In 2016, New York’s City Council passed a bill to make collision reports available through an online portal on the NYPD website, but records are rarely disclosed in full detail.

Many victims are forced to file Freedom of Information Law requests to obtain complete police records, but they are often denied.

Advocates also lament the police’s lack of transparency when it comes to releasing statistics pertaining to hit-and-runs.

In 2014, the City Council passed a bill requiring the NYPD to issue quarterly reports on hit-and-runs, but these only track “critical” incidents. Though it may be the most consequential, the yearly number of hit-and-runs resulting in “serious” injuries is still not publicly available.

23 thoughts on “Despite NYC’s Vision Zero Progress, Most Hit-and-Run Drivers Avoid Arrest”

Thanks for this thoughtful, thorough, and well-researched story.

Operating a motor vehicle – driving – is formally licensed and regulated. Informally, it’s regarded – by drivers, the mayor, the police, legislators, the governor, and district attorneys – as a right. When anything goes wrong, it’s never the driver’s responsibility; it’s always an “accident”.

Do “accidents” happen? Sure, but the burden of proving a crash resulting in injury or death wasn’t the fault of the driver should be on the driver. If you don’t want that burden, don’t operate a motor vehicle. Operating a motor vehicle is a responsibility, not a right.

What’s required: legislation eliminating any ambiguity that operating a motor vehicle safely is the responsibility of the driver. And safety is no accident.

I have a right to travel, move about, and if any distance is involved then the accepted viable means to travel is a motor vehicle. As long as any one has that right than I claim it for myself as well.

Before dismissing “accidents” maybe we should do some research on some causes. Some real intense forensic research. Which is the causation of safety: lower speed, day time driving lights, less distraction, “better road design”? Have you ever wondered how much suicide is involved in road deaths. I knew someone who threw himself in front of a car. I also knew someone who was thrown in front of a car. Of course motor cyclists are really crazy. How do you count them?

Are you aware that when it is noted that alcohol is involved in a pedestrian road fatality it is much more likely the pedestrian was “drunk”, not under the influence but “blind drunk”, and the driver was “stone cold sober”? I’ve never seen a pedestrian death on the road reported that way.

Here in NYC the mantra of biking advocates would always be that when more people cycled the biker fatalities would naturally go down. Higher visibility. But in 2017 some 23 cyclist died in road collisions. In 2016 it was only 12. The purported number of active cyclist has grown some 85% in the last decade. I’ve only heard only one advocate claim this relationship was still true. I guess he was the one who hasn’t gotten the word. It does suggest a return to common sense rules of the road for even seasoned bikers is the real “low-hanging fruit” here. I myself take the safe driving refresher course every three years.

When the number of road deaths drop, as it has consistently for many years, I think to myself that it must be drivers who have gotten the message and are putting into practice daily. Of course that me and I’m biased. But I’ve gotten myself a dash board camera to record just how many errant cyclists I let live by being cautious at intersections when they ignore the traffic controls and speed in front of my car. Mothers with strollers and talking on cell phones coming ignorantly off the curb into moving traffic(it is illegal) is another pet peeve but I’ve said enough to continue the discussion in a more informed way.

Are you aware that in the study about drunk pedestrians, the BAC level they used was 0.04%, not the same 0.08% that is considered drunk for drivers under the law?

This is without even going to go into the argument of how irrational it is to make a moral comparison between a person walking after a few drinks to someone driving after a few drinks…

CDC studies estimate that there are 112,000,000 incidents of drunk driving in the US each year.

P.S. 0.08% is a LOT of booze. Which means it’s not illegal to drive drunk, it’s only illegal to drive VERY drunk.

Last year while cycling I was intentionally hit by a speeding driver who chased me the wrong way up a one way street and accelerated at speed into the back of me. The cops had 5 witnesses at the scene who said it was intentional, and I was later told by an officer that the guy admitted to them that it was road rage, and that he “lost his mind.” Despite this, I found out recently that the DA is not pressing charges against him. So there you have it. The problem isn’t just with hit and runs. Even if you stay on the scene and admit everything, even if it was an act of intentional aggression (in my case, attempted murder), even if there were witnesses who were willing to give statements to the effect that it was an intentional act, they will still find a way to absolve the driver of any blame and let them get off scot free. Oh and I’ve been calling the DA’s office to ask for an explanation and they refuse to call me back. This guy probably has one of the NYPD’s “get out of jail free” cards handed to him by a relative. The system stinks to high heaven and has no place in this city, particularly in 2018.

You need to get yourself a lawyer and sue the driver.

@redbike, as a biker, driver and pedestrian, I see merit in all three perspectives on this issue. All three groups include responsible and irresponsible individuals. While I understand and share your frustration, it’s senseless and unfair to override the “innocent until proven guilty” principle. Better enforcement of fair laws is the answer, and it’ll cost big bucks. You’re right that driving is a privilege, not a right. And since bikers, runners and walkers rarely if ever do something that injures a driver, it’s reasonable to make drivers pay higher registration fees to cover the cost of effective enforcement. And all taxpayers should pay a little more to fund the hiring of more police and traffic enforcement officers. We all lose when any one faction bears a burden we all should share.

Fascist.

Thanks for this. I wonder how many hit-and-run incidents don’t make it into NYPD data. The SUV that hit me a few years ago sped off, but I caught the vanity plate. I wasn’t hurt badly, but the NYPD refused to file a report or follow up, even though I gave them the license plate, color, and make of the vehicle, minutes after the incident.

My hit-n-run involved no injuries but did 1500 in damage to my vehicle is not being pursued by nypd even though i had the plate number photo of driver and of his box truck. Without an arrest i cannot get restituion as he had out of state plates an no insirance and lives in brooklyn not the address on his registration. Insurance is not covering it under uninsured driver insurance because nobody was hurt.(liability only) its frustrating to say the least.

They should make hit and runs a part of compstat and evaluate precincts on their ability to reduce their occurrence and catch perpetrators. Until they do this, NYPD will not view hit and runs as a crime.

Pingback: Placard Abuse, Construction Dysfunction, and Hit-and-Runs May End Up in the Crosshairs of a Ritchie Torres Investigation – Streetsblog New York City

Pingback: Placard Abuse, Construction Dysfunction, and Hit-and-Runs May End Up in the Crosshairs of a Ritchie Torres Investigation | Holiday in New York City

Pingback: Placard Abuse, Construction Dysfunction, and Hit-and-Runs May End Up in the Crosshairs of a Ritchie Torres Investigation | Amrank Real Estate

Pingback: Nueva York consigue frenar la epidemia de muertes por atropellos en sus calles – Tribuna Liberal

Pingback: Eltingville Hit-And-Run Driver Charged – Parker Waichman LLP

Pingback: Trucker Kills Woman in Flatbush And Walks Away By Saying the Magic Words: ‘I Didn’t See Her’ – Streetsblog New York City

Pingback: Trucker Kills Woman in Flatbush And Walks Away By Saying the Magic Words: 'I Didn't See Her' | News for New Yorkers

Pingback: Dealing with Hit-and-Run Accidents in New York,Serious Injury Attorneys

Pingback: Motorcyclist Suffers Injuries in Long Island Hit-and-Run Accident

Pingback: Americans Shouldn’t Have to Drive, but the Law Insists on It | Later On

Pingback: Cars took over because the legal system helped squeezed out alternatives | Pratikar

Pingback: Car Crashes Aren’t Always Avoidable | Rapid Shift

Pingback: Americans Shouldn’t Have to Drive, but the Law Insists on It - The Atlantic - Your Legal Helpers