Adi Talwar

Sandy revealed that flooding is a risk even far inland. Parts of this intersection, at 2nd Avenue and 110th Street in East Harlem, are in the flood zone according to FEMA's preliminary new flood maps. They're also within the city's proposed East Harlem rezoning.

The polluted waters of the Gowanus Canal swelled to the lip of the Carroll Street bridge and inundated the properties on its banks. The water surged down Bond and Nevins Street, infiltrating basements and infusing homes and artist studios with the smell of sewage and gasoline. Nearby at Gowanus Houses, nearly 3,000 residents lost power and heat—a condition that continued for 10 days, stranding elder residents on upper floors. Five years after Hurricane Sandy, the residents of Gowanus still remember.

And that memory makes some of them worried about the city’s intentions to encourage development along the canal through a neighborhood rezoning. Some participants in the working groups that met this spring as part of the city’s rezoning study asked why the administration couldn’t take a different approach: to leave the canal zoned as it is, given that pretty much all the blocks running alongside the canal are in a flood zone.

One such local activist, Katia Kelly, tells City Limits that, because regular flooding and sewage overflow is a longstanding issue in the area, it makes no sense to her to develop large residential buildings. “And now you’re bringing even more residents and they’re all going to use dishwashers and take showers,” she says, adding, “What are we going to do if we bring so many more people to Gowanus and they all have to be evacuated?”

Some other stakeholders aren’t quite as pessimistic, and the city certainty disagrees: “It conflicts with core objectives established within the Gowanus Study process, including promoting investment in the creation of commercial and arts uses, housing and continued industrial use on canal-side properties,” the Department of City Planning says in its rationale, further explaining that the city’s policy is “to restrict density in areas that face exceptional flood risk, such as areas where projections of sea level rise would result in daily tidal flooding by the 2050s, and where shoreline enhancements are not feasible to address these risks.”

In the case of Gowanus, DCP argued, flood risks could be managed through a variety of other strategies, including improving emergency preparedness and investing in “infrastructure hardening, flood-proofing of buildings, shoreline raising, and/or long-term coastal protection infrastructure.” The agency has also expressed support for efforts to improve local stormwater management and drainage as part of a larger plan for the area.

DCP’s position in Gowanus generally reflects its perspective on development post-Sandy. Five years after the hurricane, while there are certainly areas where the city is limiting density and trying to protect wetlands from encroachment—places like Broad Channel, on Jamaica Bay, where the city recently passed a downzoning—more frequently the city has said it will pursue resiliency measures that allow flood-prone communities to continue developing, just more safely.

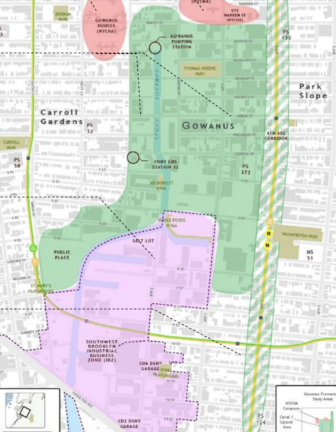

Department of City Planning

Study area for the Gowanus rezoning (the green is where the rezoning is expected to take place)

Of the 10 neighborhoods where a neighborhood rezoning is being considered or has already been approved to encourage housing development, significant portions of five of them—Gowanus, Bay Street, Inwood, East Harlem, and Long Island City—are located, or will be by the year 2050, within the 100-year flood zone. That zone is where there is a one percent chance of flooding each year as indicated in a preliminary draft of new maps produced by the Federal Emergency Management Agency (though the city says those maps have errors that result in overestimations; more on that to come). And while the majority of downtown Far Rockaway itself is not in the flood zone, it is already cornered on three sides by it.

From the perspective of the de Blasio administration as well as other advocates for affordable housing growth, it’s just unrealistic to imagine pulling back from all its many coastlines.

“We can’t retreat from the city itself; we are a city of coastal islands, and the floodplain, because of rising sea levels, is growing larger,” says Laurie Schoeman, the national program director for Resilience at Enterprise Community Partners, a nonprofit that frequently partners with the city to promote affordable housing preservation and growth. “We want to preserve affordable housing units in the floodplain and we want to ensure that all affordable housing units built in the floodplain are resilient.”

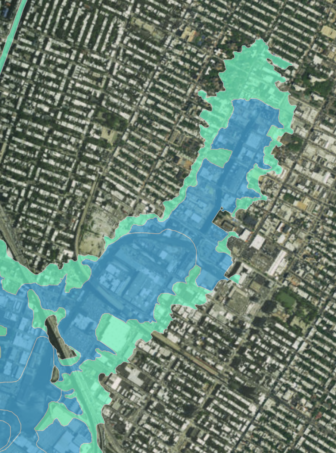

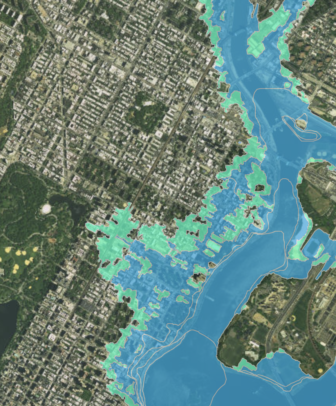

NYC Flood Hazard Mapper

100-year floodplain according to preliminary draft of new FEMA maps. Blue is the 100-year floodplain and green is the 500-year floodplain.

Not everyone may agree that the city’s housing stock needs to grow, but assuming that’s true, the question becomes whether we’re really succeeding at promoting resilient development. The answer entails multiple issues, from building regulations, to what investments we’re making, to what risks we are or aren’t taking into account.

Significant steps forward on building requirements

There’s been a good deal of effort to rethink regulations that require resilient construction since Hurricane Sandy hit in 2012. Take the city’s flood-resilient building code regulations, which apply to new or substantially improved buildings in the 100-year floodplains and mandate that living spaces and mechanical systems be elevated above a certain level, that walls below a certain elevation be built with water-resistant materials, and other requirements. A 2013 update mandated an even higher elevation level. DCP has also taken steps to make sure zoning regulations, like building height limits, don’t become an impediment to property owners who want to retrofit to prepare for flood risks. The city’s 2014 update to its environmental review manual (the CEQR Technical manual) also includes new passages on climate change.

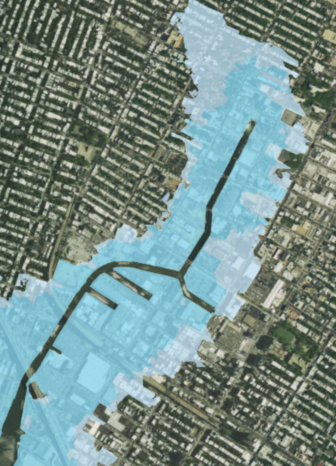

NYC Flood Hazard Mapper

Expected floodplain in 2050, using preliminary FEMA maps plus climate change predictions. Blue is 100-year, white is 500-year

Jonathan Gaska, the district manager of the Rockaway community board, says the new building standards are “significantly better than what was in place before Sandy” but adds that “the tougher nut to crack is the older homes that have been here for 30 or 40 years,” which can be extremely expensive to retrofit. Organizations like Enterprise Community Partners are trying to work with local and federal governments to obtain more financial resources to protect affordable housing from climate change.

The delineation of the 100-year flood zones has also been a point of discussion—and disagreement. In 2013, the federal government issued a preliminary draft of its updated 100-year flood maps, which greatly expanded New York City’s flood zones. An additional 35,000 buildings, for a total of 72,000 buildings and 400,000 New York City residents were now in the 100-year floodplain, according to the update, which meant thousands of additional residents now had to purchase flood insurance. The city, however, appealed those maps, saying that as a result of technical errors FEMA overestimated the size of the floodplain, with a resulting huge cost burden for homeowners.

FEMA agreed there were errors and that the maps should be revised, but for some planners, the fact that FEMA maps are often subject to such dispute is a cause for concern. “FEMA maps are considered by many to be subject to political pressure for a range of reasons to the point that they are not dependable,” argues Ronald Shiffman, founder of the Pratt Center for Community Development.

Advocates and environmentalists have also argued that requiring resiliency measures for buildings in the 100-year flood zone designated by FEMA is insufficient because those maps are based on topography and past storms and fail to account for future flood risk, which could be greatly exacerbated by climate change. A new study released this month by the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences found that the annual likelihood of 2.25 meter floods—just slightly lower than Sandy—had increased from 0.2 percent before 1800 to 4 percent from 1970 to 2005 and will further increase to an annual 20 percent likelihood between 2030 and 2045 in most of the scientists’ simulations.

In recognition of advocates’ concerns, the city and FEMA reached an agreement in 2016 that it would create two new maps: a revised map of current flood risk, as well as a new, “climate-smart flood map” that would take into account future flood risk and would ensure future flood risk is taken into account “for planning and building purposes,” according to a FEMA press release. (Until the new maps are issued, flood insurance rates are still based on a 2007 version of FEMA’s maps, while the city’s stricter flood-protection building standards are required for structures in the more expansive preliminary map.)

Enterprise’s Schoeman says that going forward, the city ought to also take into account other causes of flood risk besides coastal flooding, such as precipitation and underground water inundation, when mapping flood risk and establishing what areas should require resilient construction.

But meanwhile, the federal government’s itself has taken a step backward, to the great concern of many resiliency advocates, by removing the Federal Flood Risk Management Standard Executive Order, issued in 1977 and updated by the Obama administration. That order required all plans for infrastructure projects funded with federal dollars to consider future flooding. The Trump administration just did away with it, leaving it up to the discretion of agencies whether to consider climate’s risks in planning projects.

Promoting density in flood zones

But it’s not just that the city is updating regulations that affect developers and homeowners; it’s also promoting housing growth through rezonings, a number of which are in flood-risk neighborhoods. From DCP’s perspective, an upzoning plan, in the right circumstances, can be beneficial from a resiliency standpoint because it results in the creation of new, higher-standard buildings, as well as comes with city investments in the neighborhood’s built form.

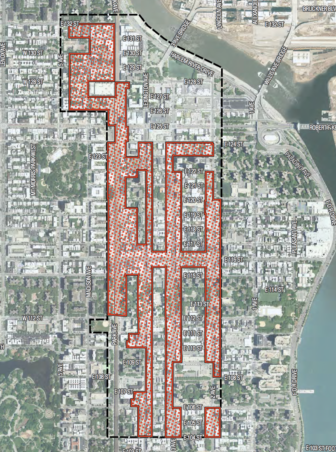

Environmental Impact Statement, Department of City Planning

An outline of the city's proposed East Harlem rezoning.

Take DCP’s East Harlem rezoning proposal, which recommends upzonings on several major corridors (including Park, Lexington, 2nd and 3rd Avenues as well as 116th Street and 125th Street) and is expected to lead to the creation of an additional 3,500 apartments. As noted in the Environmental Impact Statement for the project, the area between East 104th Street up to roughly East 110th Street and as far west as Lexington Avenue is currently in the 100-year flood zone, and according to predictions by the New York City Panel on Climate Change, that zone will expand significantly west in the future (though the technical problems with the current flood maps mean they might overstate that risk).

The EIS states that buildings within the current 100-year floodplain would be required to abide by resilient building code regulations, that buildings that are in the floodplain in the future will be able to retrofit when the time comes, and that on city-owned properties the city could potentially apply a higher standard, requiring resiliency building code standards for developments that will be in the flood zone in future decades.

NYC Flood Hazard Mapper

FEMA's preliminary update to the maps. Blue is the 100-year flood zone, green is the 500-year flood zone.

In addition, to protect the area from coastal flooding, the EIS notes that the city “has identified a potential resilience project for East Harlem in the form of an integrated flood protection system” that would be incorporated along the FDR highway or the esplanade, “subject to available funding.” This strategy is behind schedule, however: it was originally identified in 2013, with an earlier construction completion date of 2016. A city update in April indicated the city was seeking a consultant to conduct a study on the project. The Department of Parks has also committed to conducting a study of the waterfront to reduce coastal flooding and improve drainage, according to a city presentation.

Alexander Adams of CIVITAS, a planning and advocacy organization in East Harlem, supports the addition of some density to East Harlem (though not as much as the Department of City Planning has proposed), but he also wants to see the city commit to additional investments in retrofits, the reconstruction of East Harlem’s esplanade as not only a recreational resource but as a protection from flooding, and the creation of more open spaces in the neighborhood as stormwater-retention infrastructure to collect runoff from western Manhattan.

NYC Flood Mapper

Potential floodplain by 2050, based on FEMA's preliminary draft of maps as well as climate predictions. Blue is the 100-year flood zone and white is the 500-year flood zone.

Community advocates who support a rezoning in other neighborhoods spoke similarly. Bobby Digi, an entrepreneur involved in the Bay Street rezoning process and a committee member on the Governor’s Superstorm Sandy Recovery team, supports a rezoning but he’d like to see developers and planners “get a little more creative” when it comes to building resiliency infrastructure that can also serve as parkland.

Others are more skeptical. Pratt’s Shiffman and Allegra LeGrande, a professional climate scientologist who spoke to City Limits as an Inwood resident, are both concerned that when engaged in large-scale development planning, the city is not thoroughly considering all the risks of climate change and making these risks part of their upfront planning process. Shiffman says the impact of increasing density on evacuation planning and the energy grid should be given more attention, among many other issues. LeGrande and others submitted comments on the Inwood rezoning that called for an evaluation of how climate change affects every category in the EIS, from air quality to socioeconomics.

“Climate change is not something that can be relegated to a section [of the Environmental Impact Statement], because climate change is the reality that we all will be living in the future,” she says.

The city believes it assesses the risks appropriately. “The CEQR Technical Manual requires that the City conducts a greenhouse gas emissions and climate change analysis as part of an EIS. The manual is purposefully flexible to allow the lead city agency on a project to develop a methodology for the climate change analysis specific to the unique conditions of each project,” said Seth Stein, a spokesman for the mayor’s office, in an e-mail to City Limits.

The chapter he references does acknowledge issues like rising electricity and water demand, but doesn’t give thorough guidance on how to actually assess and plan for climate risks beyond the problem of flooding.

Resiliency is an equity issue

It’s not a coincidence that about half of the city’s current neighborhood rezonings are, or will be, in flood-prone areas. With some exceptions, the de Blasio administration has tended to focus on upzoning low-income or formerly industrial neighborhoods; the administration says this is because its upzonings are designed to come with a suite of investments to improve the conditions in long-neglected neighborhoods.

And a good number of low-income neighborhoods are in floodplains. East Harlem was once a wetland, and once filled in, the land was cheap, making it easier for the city to acquire for the construction of low-income housing, according to CIVITAS’s Adams. Gowanus, a heavily polluted canal and former industrial waterway, has long been more affordable than the neighboring upland communities. In Inwood, LeGrande points out, income levels decline as one goes down the hill. In the industrial age, living near the water was for low-income people; only in our post-industrial era has it become associated with luxury living.

That means that in several cases, rezonings have the potential to impact to what degree a low-income community can survive the impact of climate. To some this is what makes adding density to floodplains all the more disturbing, while to others, it’s what makes rezonings great opportunities—if, and only if, the proper investments are made to preserve the existing affordable housing stock and the neighborhoods themselves from climate change. And, if those investments happen fast enough: five hurricane seasons after Sandy, just about a quarter of the city’s coastal defense projects have been completed.

A sandy line marked Sandy's reach in Coney Island a few days after the storm.

Read City Limits’ Coverage

5 thoughts on “Retreat or Build Out? NYC’s Post-Sandy Development Dilemma”

Inwood fun fact about flooding:

Sandy flooded the popular Inwood Nature Center, a two-room 1930s Parks structure of about 3,000 SF. The space was finished minimally, but the mechanicals (a small air conditioner, boiler and electric panel) were destroyed and needed rebuilding.

As of 2017, the project is still in design and not even bid. It might reopen by 2020. For what is essentially a two-room shack. Meanwhile, a generation of Inwood kids grew up without the chance to pet snakes or enjoy Nature Center programming.

NYC is not exactly the best at building back from floods. Their credibility on anything flood-related is shot with me after this debacle.

Big pieces Staten Island’s east shore buyout areas were recently rezoned to limit, but not eliminate, new residential & commercial construction. The new rules are intentionally tough to discourage new construction. I think it would make more sense to simply rezone the affected areas as parkland and never build there again.

Special Coastal Risk District-

http://www1.nyc.gov/site/planning/plans/resilient-neighborhoods/east-shore-rezoning.page

Zoning is solely to protect health and welfare, if those responsible for its use can’t meet its most basis tenant, but go on at nausium about the urban fabric, fenestration, etc then down with zoning and the “planners”. Zoning is really only another racists institution, preserving the wealth of white landowners.

The article adds proof to the supposition that the most important things go unsaid in our society. The nation’s planning and community development policies sustain the principle of catastrophic resolution. The newly formed Chicken Little climate change wing in the sustainability laboratory circulate maps that say only one thing to its observers, “Oh, good my property is OK,” and serves as a classic bit of issue misrepresentation.

Apply the Isle de-Jean Charles climate change refugees experience to New York City. The action taken in Louisiana occurred when they were down to the last two-percent of their land. The story on the 98% of households displaced is not well known. Here is the rough math, apply the $100 million in relocation funds for the 20 remaining households on the Isle de-Jean Charles to the 35,000 families in let us say, Canarsie, Brooklyn. The public cost is $175 billion. Applying the Louisiana resettlement plan of 20HH/year; it would take a millennium to serve Canarsie. At 500 HH/year, the cost would be $2.5 billion/year, and it would take 70 years. I heard it in the boardroom – let Nature do the displacement.

Now, imagine $2.5 billion is doable because I have a seventy-year plan with a vision for a vital urban future for NYC. The purchased property would be recycled and stripped of its toxins just in time for the ocean’s rise to form an artificial reef of old foundations. Counter the initial acidity and make seafood or any of a million other possibilities. Preventing the land poverty plan currently in play would be the right approach for a place like Canarsie most likely to fill with seawater. The test should be whether a quid pro quo with vision is in place to counter change. Between the lines, this article outlines another caveat emptor slap in the face, aimed at people that will not change led by people who refuse to see change.

Initiative in the Buildings Department: https://thebridgebk.com/buildings-department-getting-act-together/