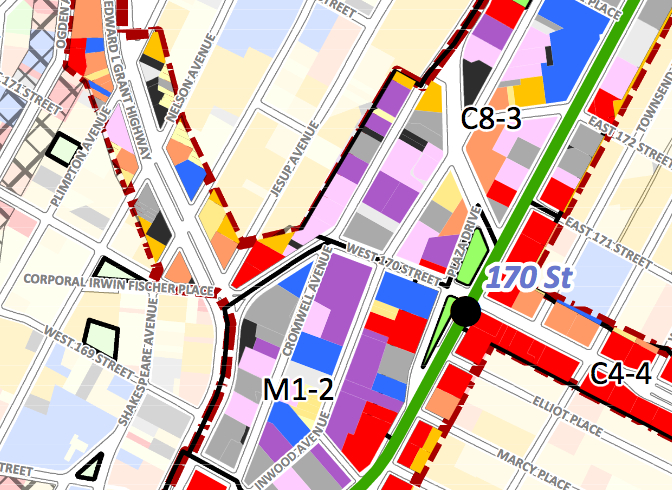

NYCDCP

Close-up of a map of the proposed Jerome Avenue rezoning area, from City Planning.

The basic background

Zoning regulates the type and the maximum size of buildings that can be built in a designated area. It joins a law (the Zoning Resolution, which specifies the different regulations) to a map that indicates precisely where particular rules apply. A rezoning is when that zoning is changed—either to tighten restrictions on building size (a downzoning), loosen those restrictions (an upzoning) or do a little of both. In 1961, New York City did a citywide rezoning, and in many neighborhoods the regulations put in place then are still in effect. Nowadays, zoning changes go through public review and require assent by the Planning Commission and City Council through the city’s ULURP process. During his 12 years in office, Mayor Bloomberg rezoned 40 percent of the city’s land area.

Why we’re talking about this now:

As part of his Housing New York plan to create or preserve 200,000 units of income-targeted or “affordable” housing, Mayor de Blasio launched two initiatives related to zoning.

First, the mayor got the City Council to change the zoning resolution through the Zoning for Quality and Affordability program—which updated a host of regulations affecting things like height, streetfronts and parking—and the implementation of Mandatory Inclusionary Zoning, which compels residential developers applying for an upzoning or taking advantage of neighborhood upzonings to set aside a portion of their new apartments for specified income groups.*

At the same time, de Blasio set out to rezone a dozen or more city neighborhoods to create room for new housing density, arguing that new housing supply was needed to ease the affordability crisis. One rezoning (in East New York) has passed, another is close to passage, and a third is working its way through the process, with other proposals at various stages of development. In many but not all cases, the proposed rezonings have been controversial, and the mayor has encountered opposition.

Every neighborhood is different, and so each local conversation about rezoning has been unique: There were deep misgivings in East New York. The East Harlem community is divided over whether to accept any rezoning. But Far Rockaway saw little opposition and followed calls by community groups for redevelopment. Community groups in Bushwick and Chinatown/Lower East Side have also have requested rezonings (with more of a downzoning emphasis, at least in some ways), though the de Blasio administration rebuffed the LES request.

Where there is opposition to a rezoning, it is sometimes about the physical impact of new buildings on architectural style and shadows, or the human impact of new residents on infrastructure like subways and parks. Also, some residents express fear of a change in demographics—that an influx of rich people or poor people will affect neighborhood character, services, quality of life and/or property values.

The strongest emotions, however, are over whether rezonings will attract new development that drives up rents and displaces low-income people. These objections reflect deep skepticism about “affordable” housing programs, which sometimes serve income groups far more affluent than the people currently living near a development site.

The city says displacement is already occurring and the rezonings are meant to channel market forces to carve out some space for targeted income groups. Critics say they encourage speculative behavior and gentrification. Decisive evidence of who is right is hard to come by.

What you need to read:

Department of City Planning’s About Zoning page

Mandatory Inclusionary Housing, explained

Comprehensive coverage at ZoneIn.org by City Limits

What you need to think about:

It is unclear whether the mayor’s approach to rezonings will be a factor in the mayoral campaign, but rezonings are a big issue in at least a few Council districts where plans are in the pipeline. If de Blasio is reelected, there will continue to be passionate discussion in several neighborhoods over his proposals—as well as attention to areas already rezoned, where people will look to see effects.

The larger issue, though, is about the process. Critics of de Blasio’s proposals often point to inequalities manifested by the city’s neighborhood-by-neighborhood approach, under both Bloomberg and de Blasio. Why must some neighborhoods (mostly low-income and non-White) accept new density when others don’t? Will citywide infrastructure—sewage, open space, transit and more—keep up with the new density the rezonings will promote? There is also criticism that the ULURP and environmental review processes don’t create avenues for meaningful community impact.

No major candidate has promoted comprehensive planning (the creation of a citywide plan, not driven by development or focused primarily on zoning) in New York City. But it seems a possible topic for progressives to take up soon.

Correction: Originally stated incorrectly that the Zoning for Quality and Affordability text amendment also changed rules regarding density.

One thought on “Election 2017 Policy Brief: The Rezonings”

At least you’re asking about infrastructure but no else is, especially our elected officials. Some neighborhoods in Queens apparently already experiencing drops in water pressure as new apartments get filled up.

The NYC zoning system is a mess but I still think it’s important for the local councilmember to have unofficial veto power over what zoning changes take place in their district.

The 1961 rezoning was massive and subject to much negotiation. The original proposals indicated higher densities in parts SI and Queens than was in the final plan. My area of SI was actually zoned R3-2 for a few months in 1961, then downzoned to R3-1, it’s been R3X since 12/2005.

Scroll down to ‘1961 Zoning Resolution’ –

https://www1.nyc.gov/site/planning/about/city-planning-history.page?tab=2