NYCHA

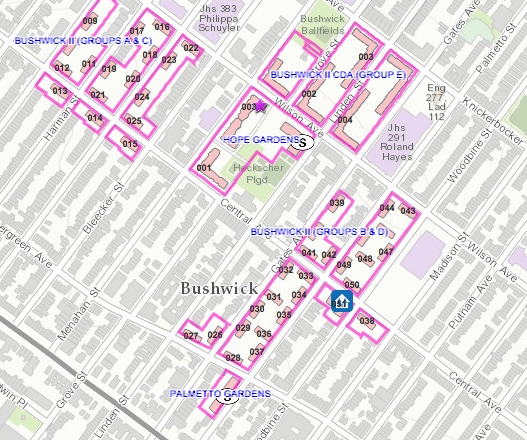

The casitas are located in the Bushwick II segments one of which is not shown on this map.

Three decades ago, a promising new chapter for public housing in New York City dawned along Central Avenue in Bushwick. On 30 acres that had been vacant for years, having been cleared for a late-stage urban renewal project that ran out of money before the “new” part could be built, the New York City Housing Authority bowed to resident demands and built 50 low-rise buildings. Black residents called them townhouses. Latinos referred to them as casitas. They were, the Times reported in ’93, unique in the NYCHA universe as low-rise rental properties.

“[I]ts success is evident in small details,” the newspaper’s Martin Gottlieb wrote of the development. “There are murals in public hallways in some of the buildings, painted by their tenants. There are tidy white draperies in some of the public hallway windows.”

Many of those touches remain at the casitas, which stand in three clusters—one near Harriman Street, the second at Palmetto Street and the third around Eldert Street. There are little gardens in the raised beds outside some of the back doors. Many of the hallways have art hanging on every wall and potted plants adding green to the landings. Lacy curtains grace the windows between the foyer and the building’s core in at least a few of them.

While those features remain, newer forces are also in play in the casitas, which are technically called Bushwick II but are sometimes referred to as part of the nearby Hope Gardens complex, which consists of three more traditional high-ride buildings.

On one hand, local NYCHA management has had a number of confrontations with the low-income organizing group East Brooklyn Congregations. Tenants working with EBC who are upset about the state of repair in their buildings have demanded group meetings with development supervisors and borough-wide NYCHA leadership, which NYCHA has declined.

On the other, NYCHA is expected sometime this month to issue a request for proposals to launch a Rental Assistance Demonstration or RAD project encompassing the Harriman Street and Eldert Street sets of casitas, a set of slightly larger low-rise buildings north of Wilson Avenue that is also part of Bushwick II and the nearby senior-citizen building known as Palmetto Gardens, which is south of Evergreen Avenue.

Unable to arrange meetings

RAD allows NYCHA to convert public-housing tenants to Section 8 voucher holders and to lease the buildings to new entities owned by NYCHA and a private entity. The change in ownership makes it easier to borrow money to fix the buildings. RAD, which already has been implemented elsewhere in the city, is one of several initiatives NYCHA is trying in an effort to close its operating-budget gap and deal with its massive backlog of repair work.

EBC is skeptical of the RAD effort, given what it says are the problems NYCHA is having responding to tenants. The organization has tried to pull off group meetings between tenants and management at Hope Gardens, Cypress Hills and Linden Houses, to no avail.

For its part, NYCHA contends “Property Management is happy to meet with residents one on one to discuss specific repairs and NYCHA is also happy to coordinate group meetings to address community wide issues. We’re grateful for the partnership of our residents and are working urgently to address the concerns presented by this organization.”

NYCHA says group meetings are a poor method for resolving individual repair issues. The authority believes residents should use the system-wide mechanism for reporting repair needs, which it says has become far more reliable in recent years. It says it has offered to arrange a public meeting with the tenants, but been rebuffed.

EBC says residents’ patience with the repair-reporting system is at an end, and that the most pressing repair problems are to common areas that affect tenants as a group.

The faceoff is partly a culture clash: NYCHA wants to strengthen confidence in the management systems it has pledged to improve through its NextGen NYCHA strategy. EBC, trying to gain credibility and build tenant power in the neighborhood, is hoping to bypass that system to get quicker results.

Waiting for repairs. Then for good ones.

But the power struggle is not the whole story. There are real concerns among residents.

Fabio Gutierrez, a tenant at one of the Hope Gardens high rises, was among the residents who tried to meet with management there back in April. The intercom hasn’t worked in three years, he says. Inside his apartment, he’s been calling for repairs to a busted folding closet for two years and has dealt with roaches and mice. “They always tell us there’s something more important in another building,” he says of local management. “But that is what they say to everybody.”

Murphy

The stairs in one casita show the kind of wear and tear that is common.

Angela Sanchez, who has lived in one of the casitas for more than 30 years, says it has been more than two years since NYCHA properly cleaned the common areas of the building. “Maybe they come once a month to pick up some trash around the building, but they don’t clean.” The vanity in Sanchez’s bathroom is rotting away because of a leak. She says cleaners used to come more regularly.

Areyls, a resident of a different casita, says, “It took us a long time just to get the stairway painted,” although that did ultimately occur, and was a major improvement. Over her 11 years in the building, she says, management has become less responsive. There had recently been a hot-water outage.

The list of local repair problems provided to City Limits by EBC earlier in the spring includes some big-ticket items, like elevators that break down frequently at 330 Wilson Avenue, stranding seniors in the lobby, which has lacked heat for several years, making it a cold wait in the wintertime. There is also the failed intercom at 120 Menahan Street, where the mailboxes are “nearly falling off the wall,” the group contends.

Then there are what would appear, in isolation, to be smaller issues, like a door to a stairwell with a doorknob and stairs showing serious wear and tear. Compared to the threats that many residents have faced over their time in Bushwick—”We fought and got rid of the drugs,” Sanchez says, recalling one past battle—those concerns might seem picayune.

But it seems precisely because of that effort that was made to save the neighborhood from larger demons that the accumulation of relatively minor issues so frustrates people like Gutierrez and Sanchez. In part, that’s because they’d be relatively easy to fix.

If fixed properly. Particularly irritating, the tenants say, is when NYCHA does a repair — but does it so poorly that it fails to improve the condition, and sometimes makes it worse. For instance, that doorknob on the stairwell door was replaced, but without a latch, so the thing cannot actually remain closed. And some of the worn out stairs were indeed touched up—but with what looks like leveling cement, leaving a chalky rough surface that seems to be more of a trip hazard than the broken stairs were.

NYCHA says it is working to improve the work that’s done at Hope Gardens and its environs. It’s brought in a new project manager, who is enrolled in a mentorship program to improve management skills, and is hiring for a new super and caretaker in the complex.

By NYCHA’s numbers, at least, conditions in the area have improved modestly over the past year. As of March 2017, across the five developments associated with Hope Gardens (Hope Gardens, Palmetto Gardens and the Bushwick II segments A&C, B&D and CDA) there were a combined 1,328 open work orders, 5 percent fewer than a year earlier. The work backlog has risen sharply in some buildings while dropping significantly in others.

One thought on “Change Looms and Confrontations Arise at Once Pioneering NYCHA Development”

Check out Community Voices Heard there is a campaign to get NYCHA to make repairs . We need as many supporters as we can get.