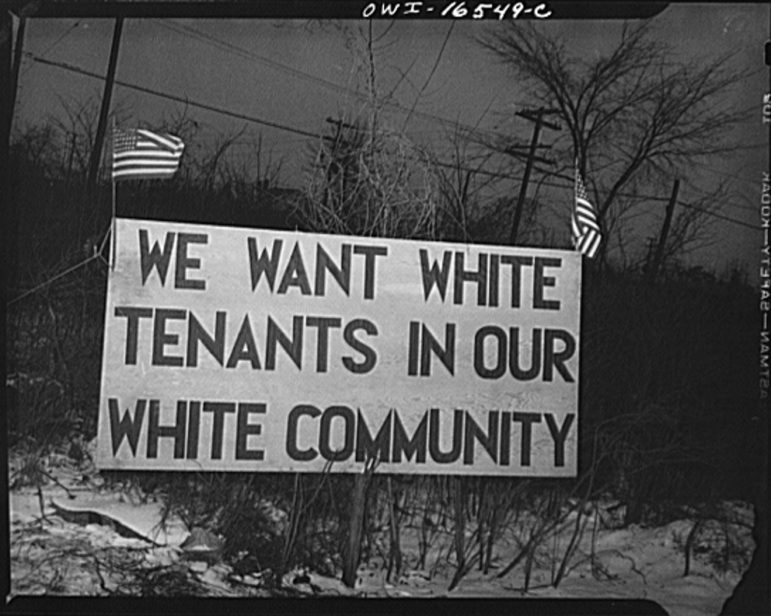

Arthur S. Siegel

Sign seen amid the 1942 disturbances at the the Sojourner Truth federal housing project in Detroit, where White neighbors attempted to prevent Black tenants from moving in.

There is a deep, pervasive history of racism in this country. Over time and in varying forms, much of this racism has found expression in land use actions, including zoning actions. As such, it is not surprising that given the current push in New York City to rezone 15 neighborhoods – neighborhoods of color comprised of working and lower income families – there is a lot of angry resistance and outright rejection of zoning proposals. So where does this skepticism come from?

Beyond recent experience of people, their friends, and family members having been displaced by gentrification over the past 20 or so years, a review of some of the much longer history of race-based land use actions helps explain the skepticism.

After the Civil War and Reconstruction eras in the South, local governments began legislating race-based zoning. That meant that certain areas, and the most desirable areas, were for “whites only.” In essence, cities were being zoned by race, with Baltimore being the first city to adopt such legislation in 1910. The Baltimore race-based rezoning was followed by similar measures in many cities across the South. After being struck down as unconstitutional by the Supreme Court in 1917, these same municipalities employed professional planners (many from the North) who assisted cities in planning that, in the words of Christopher Silver, “marshaled a wide array of planning interventions in the service of creating separate communities.”

In other words, using public works projects, such as street widenings and highway construction, to “erect racial barriers” to integration, professional planning rationale was used to accomplish the same results, but without the explicit racial animus. Even with the Supreme Court striking down race-based zoning, the (Buchanan) case may have undermined the “use of zoning to segregate explicitly by race but not the use of the planning process in the service of apartheid.”

As local jurisdictions continued to attempt to use zoning in the promotion of racial segregation, albeit through more nuanced approaches, individuals carried on that same discrimination through restrictive racial covenants that were treated as enforceable contracts by state courts. These restrictive covenants in land deeds forbade the sales of homes to non-whites. And this was the case not only in the South, but in the North as well. Below is a restrictive covenant from 1910 (ironically) on a lot in Harlem, New York City.

…and no building erected upon said premises, shall ever be used for the sale of liquor, wine or beer or be rented wholly or in part to or occupied by Negroes or colored persons…and further that this covenant against nuisances shall attach and run with the land…

It is difficult to read this and not be struck by the characterization of people of color (and others, which historically included immigrants) as comprising an acceptable category of nuisance. This of course is not surprising. Racism is in this country’s DNA and has manifested, and continues to manifest, in direct, indirect, varied and nuanced ways.

So even though the United States Supreme Court outlawed the use of zoning to explicitly restrict housing access on the basis of race in 1917, and then ruled that states were not allowed to enforce racially-restrictive land covenants in 1948, it was not until the Fair Housing Act of 1968 that the use of such restrictions were outlawed altogether. 1968! That was not that long ago.

But even though such restrictions were outlawed by degree and over a long span of time, it was still official government policy – including federal government policy – to discriminate. Even back in the Depression era, in the progressive Roosevelt Administration, official government policy lauded segregation of the races as the most effective way to ensure social peace and harmony. This official policy had real world impact through a government practice known as Redlining.

Redlining was official government policy that stood for the proposition that the presence of people of color in any given neighborhood, particularly blacks, was proof of neighborhood blight or potential blight. Maps were actually created and where non-whites and immigrants made up the population of a neighborhood, that neighborhood was redlined (literally, a red line was drawn around that neighborhood or neighborhoods), making it ineligible to receive federal mortgage insurance. This made it impossible for people of color to finance the purchase or upgrade of their homes. This resulted in certain urban areas being deprived of financial resources for reinvestment. And again, just as was the case with restrictive covenants, redlining remained government and private financing practice until 1968.

In the post-World War II period the federal government invested in the federal highway system, which combined with federal housing assistance, resulted in the creation and eventual expansive of the suburbs from the East to the West coast – not to mention the wholesale destruction of urban neighborhoods and displacement of hundreds of thousands of people. But due to redlining, racial steering, restrictive covenants, and fear of having areas redlined, opportunities to live in new suburban homes were reserved primarily for white working and white middle class families.

With massive resident flight to the suburbs, starved of financial resources and deprived of federal government support, cities began to struggle. Urban governments sought to counter “white flight” through investments intended to attract the white, middle class back to the cities. They attempted to do that through “slum clearance” programs intended to clean up blighted areas. But this mostly resulted in the destruction of urban residential neighborhoods in favor of arts and cultural centers, arenas, convention centers and the like. Purportedly, urban renewal efforts sought to eliminate poverty but what government did was simply eliminate entire neighborhoods where people of color resided, primarily Blacks. Thousands of neighborhoods were destroyed through urban renewal projects, two thirds of those neighborhoods being Black neighborhoods, and three-quarters of those neighborhoods being comprised of people of color. In New York City alone, over 100,000 Blacks were displaced, leading author James Baldwin to refer to “Urban Renewal” as “Negro Removal.”

As urban renewal forced thousands of people from their struggling, yet functioning neighborhoods, people of color were forced to squeeze into remaining redlined areas not entirely destroyed by urban renewal. This occurred at the same time that the great migrations of Southern Blacks (escaping Jim Crow and violence) continued and Puerto Ricans (escaping the market capitalization of the island) occurred. But as these new groups increased in numbers, as so many different ethnic groups did before them, manufacturing and other entry level city jobs were disappearing, because of a shift away from an industrial to service based economy. Without financial resources and economic opportunities, and with the market abandoning areas like the South Bronx, the city adopted a policy of Planned Shrinkage – a policy that basically removed fire, police and other essential city services to accelerate neighborhood decline and encourage people to move on their own to other, less marginal, areas. In many parts of the city, including the South Bronx, 70 percent of housing and its population were lost during the 1970s.

Throughout this saga of government actions designed to force or promote what was billed as desirable change, certain people suffered, but others not only benefitted but made out like bandits. Is the same saga playing out today?

Currently, the mayor is implementing a massive housing production and preservation program. But the question that was relevant years ago is still relevant today — who will benefit and who will suffer?

Current city programs will be largely unaffordable to the residents of the South Bronx and other neighborhoods. And even though the city is now open to changing financing terms to reach lower-income tiers, these efforts need to dig deeper into affordability so that local residents will benefit from truly affordable housing programs.

(Meanwhile, some forces outside of city government—opposed, it’s worth noting, by the de Blasio administration—are, after a century of de facto racial segregation, telling the current generation of people most affected by race-based measures that, in the name of federal fair housing regulations, they must not expect to be given preference for newly developed housing over those of other ethnic backgrounds and higher incomes from other neighborhoods.)

We are now in our fourth year of the de Blasio administration. To be sure, this administration has pushed forward some very significant progressive measures, among them: instituting universal pre-K, enhancing legal services for at risk tenants, supporting municipal unions, creating municipal IDs, improving traffic safety and of course pushing for and obtaining two years-worth of rent freezes for the 70 percent of New Yorkers who live in rent-regulated housing.

But when it comes to land use, residents in neighborhoods of color, those same neighborhoods overwhelmingly targeted for up-zonings, simply do not trust this mayor, and for good reason. When confronted with the ravaging effects of gentrification, displacement and homelessness, this administration repeats its mantra that “zoning does not cause displacement”—or at most, that displacement was going to happen anyway. This argument presupposes that rezoning initiatives increase housing supply and that increase in supply will assist everyone regardless of who directly benefits. This is nonsense and those most at risk of displacement know it.

And because the outcomes, regardless of intent, are race-based, meaning that people of color disproportionately suffer and people of non-color benefit, the experience fits into a recognizable pattern of racial discrimination in this country that goes back more than 150 years.

We are all conditioned – especially in this city – to deal with change. But history has taught us that when government uses its enormous powers to force or promote change, there is a price to pay and the same people always seem to be the ones holding the bill.

Most residents in rezoning areas are not against investment. Most are not against planning, or even rezoning. But given historical experiences that have led to massive waves of displacement, there is more than sufficient rationale to have a jaundiced eye and simply oppose all such government-sponsored land-use planning initiatives. In other words, fighting rezoning of neighborhoods makes perfect sense for people who have struggled and suffered through successive rounds of harmful government land-use actions.

In light of this, and regardless of public-sector intentions, be they good or bad, the city should not presume support, but work all that much harder to gain support and the trust of the people who are accustomed to being exploited and who are, quite frankly, not willing to be further victimized.

Harry DeRienzo is president of the Banana Kelly Community Improvement Association.

One thought on “CityViews: America’s Racial History Breeds Distrust of Land-Use Policies”

Very timely history lesson. It also serves to drive home the point that despite even the very best of intentions, government-driven planning in communities and neighborhoods that are populated primarily by non-whites always results in massive displacement of families, disruption of lives, destruction of communities and neighborhoods, inability of community residents to put down deep roots, and decreased opportunity to grow wealth.

It is essential then for this administration to make serious efforts to engage the residents of the communities being affected by the planned upzoning(s) in meaningful discussions on the way the redevelopment will be implemented. Current residents are stake holders in their communities, and should not be the designated losers in these government-sponsored initiatives.

In particular, the city administration should rethink their policy of using public monies to guarantee private profiteering and getting almost nothing in return — nothing, that is, that benefits the folks whose tax dollars are being dolloped out to developers who use the windfall to subsidize their market rate apartments in the buildings being constructed.

One approach the city has so far failed to consider is to not attempt to impose wealth on the community of color by uprooting current residents and replacing them with wealthier folks, mostly of a different racial group, but to develop wealth from within the community by training and employing residents already in the building trades so that they can begin career-oriented jobs that lead to better wages. That money will be spent in their own community, generating indigenous wealth, and be the impetus for economic growth. All of this with little or no displacement and other historical harms brought to people and communities of color.