From the East Harlem Neighborhood Plan

The Department of City Planning just released the latest draft of a proposed rezoning of East Harlem. The ULURP clock is now ticking, with the community board slated to vote on the proposal by early July.

And now the community coalition assembled by Speaker Melissa Mark-Viverito is mapping out what changes it will fight for before a final City Council vote takes place.

The moves this week comprise a key point in a complex process. In 2015, after Mayor de Blasio announced East Harlem would be studied for a rezoning, Speaker Melissa Mark-Viverito appointed a steering committee of organizations to collect input from the community on a wide variety of topics, from housing preservation and zoning to seniors and schools. The result was the East Harlem Neighborhood Plan, a set of 232 recommendations released in February 2016.

The Department of City Planning then came up with their own zoning plan that incorporated some, but not all, of the steering committee’s zoning suggestions. At the December scoping hearing, the steering committee commented on this draft plan, asking the city’s plan be made more like their own. But the version of the plan that entered public review yesterday had not been changed in response to this feedback.

Now the steering committee is girding for the next chapter in the discussion of East Harlem’s future. City Limits obtained a draft of the list of the committee’s priorities—a list that has yet to be released and might later be developed in greater detail. The full document can be viewed here. The priorities will be publicly presented at the Community Board 11 Rezoning Task Force Meeting on May 4, 6 pm at the Bonifacio Senior Center, 7 East 116th Street.

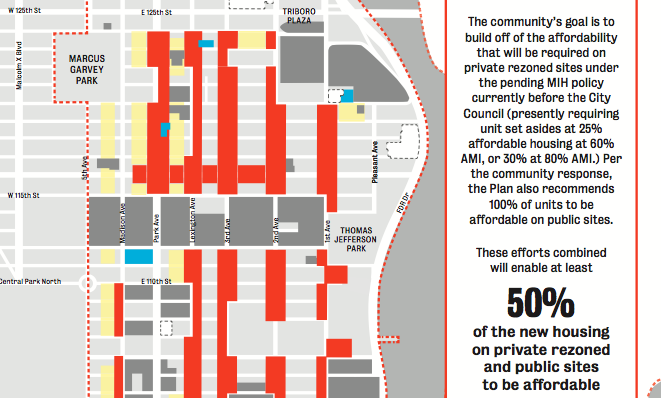

There are no surprises. The list includes the kind of demands the steering committee has been making for months, such as 100 percent affordable housing on all city-owned sites with 30 percent of units for families making less than $24,480, a certificate of no-harassment program to prevent the displacement of rent-stabilized tenants, and a request that density be increased just enough to trigger the mandatory inclusionary housing policy, which requires that 20 to 30 percent of development be affordable.

Ultimately, the success of the steering committee’s push will depend not only on its negotiations with the de Blasio administration, but on the willingness of one of its members—Mark-Viverito herself—to fight for these priorities. At the end of this year, it will be up to the speaker to cast the ultimate deciding vote on the rezoning of her district.

City Limits asked Mark-Viverito whether she would fight for the priority recommendations, though admittedly they are not yet finished.

“The East Harlem Neighborhood Plan process brought together local stakeholders to develop a vision for the future of our community,” Mark-Viverito said in an e-mailed statement. “We look forward to reviewing the rezoning proposal presented today and to ongoing discussions with the administration on the broader set of recommendations laid out in the Neighborhood Plan.”

Terms of battle begin to emerge

There are already signs that the city is resistant to some of the steering committee’s asks.

In December, the steering committee requested that the city make their rezoning proposal more like the East Harlem Neighborhood Plan by lowering proposed density levels on Park and Third Avenue and expanding the geographic boundaries of the rezoning area to the south and east. Neither of these suggestions were adopted by the city in the most recent draft of the proposal introduced on Monday.

In a document called the Final Scope of Work, DCP provides counter-arguments to these suggestions, asserting that Park and Third Avenue are well positioned near transit and wide enough to absorb considerable density, allowing for the creation of more affordable housing and more economic activity.

DCP also notes that the agency considered the larger geographic boundaries proposed by the East Harlem Neighborhood Plan but ultimately selected an area that they believed “provided the greatest opportunity to create additional affordable housing units” and meet other neighborhood goals.

The steering committee’s draft list of priorities reiterates these concerns, though notes that if it’s too late for the city to extend the rezoning farther south and east, that the city should commit to a follow-up rezoning in the near future.

The development of public land is another topic where tensions have emerged. The steering committee wants 100 percent affordable housing on public land, with at least 20 percent of units set aside for families making below 30 percent AMI, or $24,480 for a family of three, and the use of non-profit affordable housing developers and community land trusts to help ensure the housing remains permanently affordable. The document lists nine public parcels in the neighborhood, among which four have not yet been discussed by the city for redevelopment.

For other parcels where discussions have taken place recently, the city has appeared to embrace some, but not all, of the steering committee’s recommendations. At two sites (111th Street ballfields and Lexington Gardens II) the city has announced plans to subsidize two, 100 percent rent-restricted housing developments, each with the recommended 20 percent of units for families making 30 percent AMI, though the city has decided to work with for-profit developers.

At the 126th Street former MTA Bus depot, another city site, the city has only promised that at least 50 percent of the units will be rent-restricted.

In the Final Draft Scope of Work, DCP notes that additional subsidies can be used on public sites to reach deeper levels of affordability, but does not say the city will ensure 100 percent affordable units on all public sites in the neighborhood.

The steering committee also continues to push for changes in how the city assesses the environmental impact of the rezoning, in particular how it gauges which sites are likely to be developed and what the need for school seats will be in the denser neighborhood of the future. The committee is still pushing for the Department of Sanitation to consolidate its operations in the area. And the committee wants guarantees that NYCHA tenants will be given the decision-making power on whether to develop additional housing on their campuses.

The de Blasio administration has resisted all of that.

Other investments TBD

Some of the steering committee’s priorities go beyond the rezoning. The committee wants the passage of taxes to deter land warehousing or real-estate speculation, as well as more resources for non-profit affordable housing developers, support for community land trusts, and funding to hire a coordinator for a neighborhood-wide affordable housing preservation strategy.

The city’s Department of Housing, Preservation and Development is expected to release its own plan for the neighborhood within the coming week. The city has already said it provides free legal services to tenants and legal guidance from the Tenant Support Units, actively prosecutes bad landlords, is working to bring more landlords under affordability agreements, and is collaborating with a working group to explore the feasibility of a certification of no harassment program on a citywide level, with results expected later this year.

The priorities list also calls for investments in small businesses, workforce programs, school programming, school capital needs, neighborhood parks, infrastructure, and local NYCHA complexes (no less than $200 million), among other initiatives.

And the committee wants assurances that the rezoning will lead to the creation of apprenticeship programs and living wage jobs for local residents. It calls for mandates that developers receiving public benefits or building on public land participate in the city’s local hiring program, HIRE NYC (something the city already requires) as well as for the city to use incentives to get private developers to pay living wages.

So far, a variety of city agencies have met with steering committee subgroups to present what they are already doing for East Harlem and citywide, but its yet unclear what additional resources and policies they will be willing to offer. Those plans, DCP told the City Planning Commission on Monday, will be announced in the coming months.

It’s worth noting that one steering committee member, Community Voices Heard, has called for more units for extremely low-income families–40 percent on public sites instead of 20 percent. In addition, some neighborhood residents felt the East Harlem Neighborhood Plan process did not truly represent the community, and protest that any rezoning will greatly exacerbate gentrification and displacement.

2 thoughts on “East Harlem Stakeholders Plan Push Back on Elements of De Blasio Administration Plan”

No developer can profitably build 50% ‘affordable’ apartments anywhere in NYC. But don’t let deBlasio force the rezoning on your neighborhood.

This is not true. In East New York former Councilman Charles Barren has had developers build 100% affordable housing and make money. No they won’t get super rich, but they still made a profit! So it can be done! As they say if there is a will there is a way!