N.Y. World (NYPL Scan)

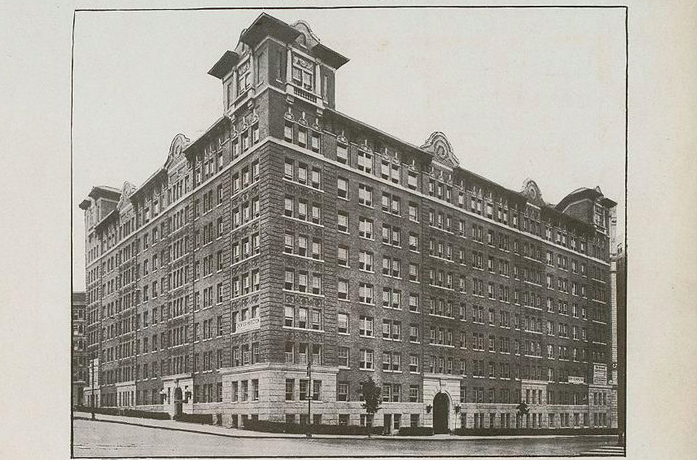

A photograph of The Grinnell, at 800 Riverside Drive, at the time of its completion in 1910. The building later became dilapidated, was taken over by the city and converted by tenants into an HDFC.

As City Limits reported in February, the de Blasio administration has proposed a new regulation for Housing Development Fund Corporations (HDFC), a type of cooperative originally formed by tenants in foreclosed buildings. The proposed new regulation is controversial because, among other reasons, it would require HDFCs receiving a new, larger tax break to abide not only by income restrictions on new buyers, as buildings currently do, but also by price caps on the sale of units.

Proponents of the regulation say buildings receiving government tax breaks should be required to preserve affordability for the long term. But, as the HDFC Coalition pointed out in an e-mail to City Limits, HDFCs are not the only kind of co-op that enjoys some type of property-tax assistance: market-rate coops do too, but don’t have to abide by resale or income restrictions. That would seem to raise questions about why shareholders of HDFCs should be compelled to comply with price caps in order to get a tax break.

HDFCs and market-rate coops receive different types of tax assistance. Most HDFCs currently benefit from the Division of Alternative Management (DAMP) cap, a maximum assessed value set by the city. Instead of getting their taxes levied based on the actual accessed value of the building, these HDFCs pay taxes on the value up to the cap, which this year is $9,787 per unit. In addition, according to data from the Urban Homesteading Assistance Board, about 10 percent of HDFCs pay no property taxes under a variety of different programs, with some of these abiding more stringent regulations like price caps. The city’s proposed regulation would apply to the other 90 percent of HDFCs and create larger tax benefits, especially for buildings in poorer neighborhoods where buildings already have a low value.

Market-rate coop shareholders and market-rate condominium owners benefit from a different tax break—the Cooperative and Condominium Tax Abatement. The abatement was created in 1996 after coop and condo owners argued that it was unfair that they are taxed at the same rate as income-generating rentals, while owners of small homes are charged at a lower tax rate. Under the abatement, coops and condominium buildings can subtract between 17.5 and 28.1 percent of their taxes, depending on the worth of the building, with higher-value buildings getting a smaller discount. The city does not allow HDFCs to apply for the abatement because they already have the DAMP cap.

More practically, how do the benefits compare in terms of the percent of full property taxes that shareholders end up paying in market-rate coops verses HDFCs? The answer is, it depends on the building.

Market-rate coops and condos will always end up saving on 17.5 to 28.1 percent of their taxes. As for HDFCs, the cap set by DAMP is a great benefit when the building is located in a pricy neighborhood and the actual value of the building is likely to be high. But when an HDFC is located in a poor neighborhood and the actual value of the building is low, the maximum set by the cap doesn’t help and the building ends up paying their full property tax.

HPD did not provide data on the benefit received by each HDFC by press time, but one HPD presentation provides a list of 33 HDFCs throughout the city. From this sampling, about half the HDFCs receive a percentage benefit that is better than what market-rate coops receive. The other half (often the ones in poor neighborhoods) receive savings between 17.5 and 28.1 percent—the same as market-rate coops—or less. The sampling is not a perfect survey; it leaves out examples from the 10 percent of buildings that get the 100 percent exemption, and some other types of small tax benefits for which market-rate buildings can apply are included in the data, like STAR. Advocates for a price cap from UHAB say that the sampling may slightly underestimate the number of HDFC buildings that get a better benefit.

According to the same presentation, the city’s new property tax exemption, which requires price caps, would ensure all 33 of the HDFCs on the list got a better percentage tax benefit than market-rate coops. About 15 percent of these HDFCs, especially ones in poorer neighborhoods, would get a 100 percent exemption. The others would get a benefit ranging from 38 percent to 99 percent.

UHAB staffers note that HDFCs benefit not only from property tax abatements, but from other city resources, including city funds used to renovate buildings when they were first entering the program, and low-interest loans and grants. Furthermore, they argue that because HDFC shareholders are homeowners rather than renters, many have benefited from low maintenance fees in neighborhoods where rents are now through the roof—and, they say, the newly proposed price caps will still allow a reasonable return on investment.

But it’s also true that HDFCs have received very different levels of city support. HPD did not provide an estimate of how much city assistance each building has received by press time. With a cap, shareholders would make different returns on investment depending on when they bought into the building, with newer shareholders making much less of a return.

No matter how much help HDFCs received before, or would receive under the new cap, some will still argue that the purpose of the HDFC program should be not just to create low-income housing, but help low-income people—many who were originally the tenants of run-down buildings, and some who are low to middle-income people who bought in later—and that it is antithetical to that goal to impose price caps.

Furthermore, some might dream of a world where all coops and condos, especially the market-rate ones generating unfathomable returns, abided by price restrictions. That, is not the legal framework we currently have, but some are fighting for reforms to ensure buyers of pricy homes do pay a fairer share of their taxes.

4 thoughts on “City-Sponsored vs. Market-Rate: Which Coops Get a Better Deal from the Tax Man?”

What is the legality of this controversy?

From Article XI Section 573:

3. The certificate of incorporation of any such corporation shall, in addition to any other requirements of law, provide:

a. that the company has been organized exclusively to develop a housing project for persons of low income;

b. that all income and earnings of the corporation shall be used exclusively for corporate purposes, and that no part of the net income or net earnings of the corporation shall inure to the benefit or profit of any private individual, firm, corporation or association;

– See more at: http://codes.findlaw.com/ny/private-housing-finance-law/pvh-sect-573.html#sthash.IhHhlk5s.dpuf

I appreciate the HDFC Coalition for bringing this issue to your attention. Many shareholders want an opportunity to address this issue with HPD before the City Council has to vote on the proposed Regulatory Agreement. They want a voice in any changes to their R. A’s

Under the present changes to the RA where the DAMP tax would be eliminated, the insistence on keeping HDFCs for moderate income households does not hold. Without the tax exemption, HDFCs would be assessed at market-value, thereby bringing the maintenance to market rents accordingly. Many of the shareholders who’ve lived in their homes for over 25 years, are in their 50s and 60s+ by now, and could no longer afford to stay in their homes.

It is nonsense! It is cynical. It is deceptive.

I’ve never thrown out a bushel of apples because a few were rotten!

Pingback: From Georgia To NYC: Civil Rights Roots Of Community Land Trusts | PopularResistance.Org