RPA

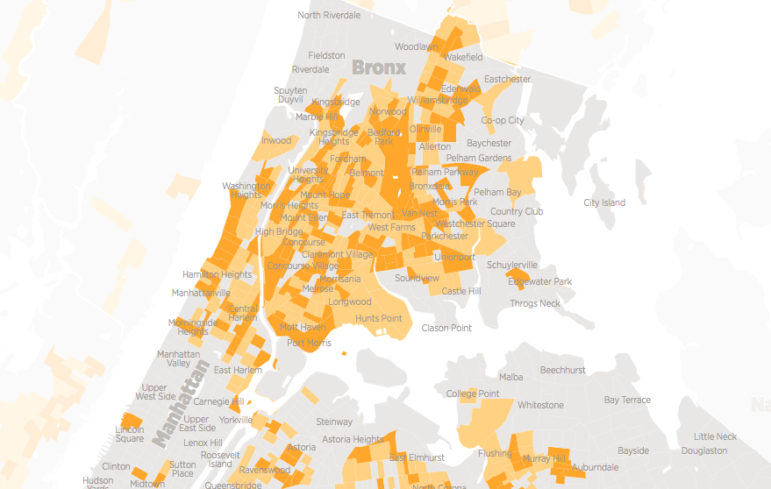

A map from the report indicates areas at risk. The darker spots display deeper vulnerabilities.

Nearly 1 million people in the metropolitan region are at risk of displacement as low wages and real-estate investment combine to make large swathes of the tristate area unaffordable to working-class households. And public policy can exacerbate the problem if it isn’t deliberately designed to address it.

Those are the conclusions of a report issued on Wednesday by the Regional Plan Association. Two-thirds of the people RPA found at risk of displacement live in New York City, but the rest are spread throughout the region, from Torrington in northwest Connecticut to Trenton and from Ronkonkama in central Suffolk County up to Orange County’s Middletown.

Within New York City, Brooklyn has the largest number of households at risk—more than 540,000—while 71 percent of Census tracts in the Bronx are considered vulnerable, the highest share among the boroughs.

RPA, working with a roster of community partners, produced the report as part of its development of a Fourth Regional Plan for the New York City area.

The report identified communities where there are concentrations of people paying a large share of their income for rent. Researchers layered that data onto a map identifying the kind of walkable, transit-rich neighborhoods that have proven attractive to wealthy renters and buyers. They then looked to see whether any of the areas that combined human vulnerability with physical allure were already seeing shifts in the real-estate market.

One finding: From 2000 to 2015, 160,000 households making more than $100,000 moved into the accessible neighborhoods, while 61,000 households making less than $100,000 moved out.

The boilerplate backstory to these trends is that these households are the victims of the city’s success at driving down crime and improving quality of life. Broader trends in real-estate investment and income inequality also get a share of the blame. But a profound thrust of the report, and of the conference RPA and the Ford Foundation presented on Wednesday, was that displacement is not an accident—that public policy has helped to worsen the problem, and has to be reshaped to address it.

“The region’s affordability crisis can only be solved if we build enough new homes that are affordable to households with a range of incomes,” the report reads. “But new development doesn’t have to come at the expense of existing residents. There are many approaches that can help protect vulnerable residents from displacement due to escalating price pressures. This report outlines five potential strategies.”

Specifically, RPA calls for a right to counsel in housing court, stronger rent regulations, more voucher programs to help low-income people pay their rent and using government-owned land for permanent affordable housing. Most important, RPA calls for governments to consider displacement risk in local decision-making, including land-use decisions.

That recommendation addresses a key dispute that has emerged as the de Blasio administration pursues rezonings in a dozen neighborhoods: namely, whether rezonings can trigger displacement and gentrification. At the very least, evidence points to a significant risk of displacement and because of the sites the administration has selected for rezonings, those risks are being borne primarily by communities of color.

Making matters worse, “The city’s environmental review process underestimates this problem,” said Michelle de la Uz of the Fifth Avenue Committee, one of several nonprofit housing developers in the audience. She pointed to risk assessments prepared ahead of the Bloomberg-era Fourth Avenue rezoning that assumed that any building that was 100 percent occupied couldn’t possibly be demolished. That assumption was off. Now, she said, “There’s an opportunity to correct the mistakes of the past.”

Maria Torres-Springer, commissioner of the Department of Housing Preservation and Development and a panelist at the event, didn’t directly address whether rezonings create a displacement risk, focusing instead on perceptions: “What we try to do is be very cognizant of the fact that even it doesn’t happen, there’s a real fear of it on the ground.” To address that fear, she said, the de Blasio administration has applied a multifaceted approach: lots of new and preserved affordable housing, mandatory inclusionary zoning, legal help for tenants in housing court, and more.

Echoing the theme of Mayor de Blasio’s state of the city speech last month, Torres-Springer noted the affordability crunch is as much about wages as it is about housing costs. “You can’t think about displacement just by talking about housing,” she said.

Dina Levy, director of community impact and innovation in the office of the state attorney general, noted that investment activity is a big part of the housing crunch. The challenge for policymakers, she said is, “There’s sort of a fine line between predatory behavior and illegal behavior. … It is not illegal to make a bad business deal.”

Sitting on a second panel, Furman Center director Ingrid Gould-Ellen insisted, “The answer can’t be that we don’t want growth,” but rather that safeguards be put in place. She added: “We just have to be very vigilant to make sure the growth is inclusive.”

The problem, Councilman Antonio Reynoso said, is that “the laws and policies and safeguards are really being outpaced by the development.” He called for a citywide approach. “So long as we look at it neighborhood by neighborhood and councilmember by councilmember it’s going to be poor neighborhoods fighting to get more affordable housing and rich neighborhoods fighting to get less.”

RPA’s report included the voices of people displaced by development, in some cases development that was facilitated by public policy decisions. “There’s not just a fear of rezoning,” said Afua Atta-Mensah, executive director of Community Voices Heard. “People are living through gentrification. It’s not a fear. It’s real, lived experience.”