Todd Schaffer

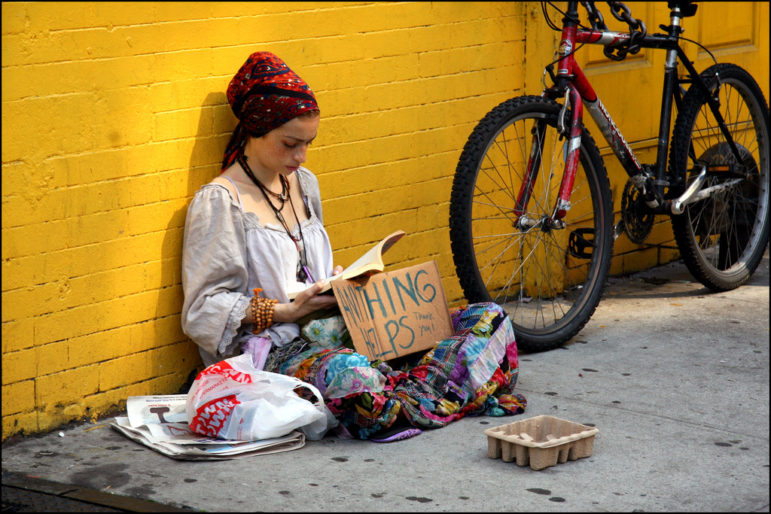

Unaccompanied homeless young people are typically between 16 and 24 years old, sometimes younger. Largely as a result of their negative experiences with police and institutions, as well as disproportionate experiences with trauma and vulnerabilities to violence on the street, they are extremely difficult to locate.

Two weeks from tonight, New York City will embark on its annual HOPE effort where volunteers will engage a small number of those living on the street. For four days afterward the city will conduct the Youth Count, a tally of homeless youth primarily conducted through post-HOPE surveys of a limited number of youth-serving organizations.

The number of street-homeless youth found during the one-night HOPE effort and post-HOPE surveys will generate a “baseline” estimate used by federal officials to judge progress in the federal goal of ending youth homelessness by 2020. This number will also, most likely, be used as the official number of street-homeless youth in New York City for years to come.

The stakes of a single tally of the city’s homeless youth have never been higher.

A combination of the city’s continued criminalization of street homelessness, its efforts to prevail in a class action suit brought against it for a right to shelter for homeless youth, and a steadfast commitment to the austere and insufficient HOPE methodology, form the decisive contexts of this years’ count. The federal priority of ‘ending youth homelessness’ by 2020 makes generating an official number all the more urgent.

Yet, the city is not prepared or committed to accurately counting homeless youth that survive in the margins each night. Homeless youth are made invisible by administrative choices, and they are continually, and woefully, undeserved. This needn’t be the case.

Policing the Homeless

Mayor de Blasio has continued the long city tradition of criminalizing street-homelessness. This criminalization means that any figure of those living in public places is going to be grossly inaccurate.

The city has had little tolerance for those taking refuge on the streets. As under previous administrations, de Blasio’s NYPD have waged aggressive campaigns against the street-dwelling homeless. Perhaps the watershed moment for de Blasio was the clearance of a purported public drug-den in the South Bronx, with a photo-op of him pointing toward the air, Sanitation workers at the ready. He told The Daily News, “I don’t believe a homeless encampment is an acceptable reality in New York City in 2015.” The News pointed out that the police had a list of nearly 100 spots “where the homeless congregate,” with many encampments “so established they include furniture and makeshift housing structures.”

With the mayor in disbelief, the NYPD and the Department of Homeless Services (DHS) went to work. The News explained, “Outreach workers with the Department of Homeless Services have visited many of the sites in recent weeks, informing the people who live and gather there that their camps will be dismantled and their presence no longer tolerated.”

Since then, homeless people, organizers and service providers have voiced grave concerns about the mayor’s aggressive approach toward the street-homeless.

Their concerns have fallen on deaf ears.

This month the comptroller’s office settled one suit, originating in 2015, pressed by homeless individuals and the NYCLU after Sanitation workers dumped the personal belongings – identification, medicine and so on – of three street-homeless men. The day that advocates held a press conference celebrating the victory, video surfaced of workers tossing the belongings of a disabled street-homeless man in Brooklyn. “Move along” orders, personal-effect dumps, and arbitrary detainment and release are protocol in de Blasio’s New York.

In this context, the simple reality is that an accurate estimate is policed out of possibility. For homeless youth in New York City – overwhelmingly youth of color who face disproportionate and high-stakes engagement by the police – the criminalization of homelessness means that many avoid the NYPD at all costs. They often avoid being in one public place for long-periods, or are quickly pushed – by police and other authorities – from place to place. That some HOPE teams include police escorts potentially increases the likelihood that folks on the street will not be counted.

How Many Homeless Youth Are There? That’s a Political Matter

Counting the homeless population, in a city as large as New York, is a Sisyphean task. Successfully counting homeless youth is likely to be harder.

Who are ‘unaccompanied homeless youth’? Unaccompanied homeless young people are typically between 16 and 24 years old, sometimes younger. Largely as a result of their negative experiences with police and institutions, as well as disproportionate experiences with trauma and vulnerabilities to violence on the street, they are extremely difficult to locate. Staying hidden is a survival strategy. They often experience the stigma of homelessness acutely and do all they can to not “look” homeless, aiming to blend in with other people in their age group.

Historically, city officials have discounted counts of homeless youth. In 1983, using data from service providers, advocates estimated there were 20,000 homeless youth, between 16 and 21 years old, in New York City. They assessed services available to these youth as “inadequate, haphazard and piecemeal.” The Human Resources Administration responded by stating that the report “overdramatizes the extent of the problem, underrepresents the current services, and oversimplifies the solution.”

In 1997 the Giuliani administration commissioned a study on the needs of homeless youth. Out of disagreement with the findings, the administration barred its release. In 1999 the Village Voice published a summary, which cited “estimates of 15,000 to 20,000 homeless youth in New York City.” Of 432 “street youth” surveyed, “more than a third…earned money through prostitution.” Officials publicly stated that “it’s impossible to count the actual number of street youth.”

The de Blasio administration also continues to discount estimates of homeless youth in New York City. This is particularly surprising given the past involvement by city officials in advocating for the needs of homeless young people.

In 2006 the City Council, with then-Councilman de Blasio’s support, funded a count and study of homeless youth. The Empire State Coalition for Youth and Family Services coordinated the effort.

The findings were striking.

On any given night “over 3,800 young people were homeless in New York City,” and “1,600 of those young people spent the night outside, in an abandoned building, at a transportation site or in a car, bus, train or some other vehicle.” Finally, “150 of our children spent the night with a sex work client.” Most were youth of color, more than third were LGBTQ. The authors noted that it was “likely to be an undercount” due to “resource constraints” and because “neither a complete census nor a household survey was undertaken.” In other words, it was a conservative estimate.

In 2008, then-Councilman de Blasio co-chaired a hearing focused on the coordination between the Department of Homeless Services and the Department of Youth in Community Development. A summarizing report from the hearing began:

“According to a recent City Council sponsored count of RHY, approximately 3,800 young people are homeless each night. […] It should be noted that these are conservative estimates. Many researchers have noted that RHY are difficult to count given their mobility, avoidance of shelters, and reluctance to report their homelessness.”

It probably wasn’t until 2014 when the 3,800 number seriously came under scrutiny. There were two central reasons for the administration’s efforts to come to narrower estimate of the city’s homeless youth population. First, in 2013, the Legal Aid Society – under the leadership of Steve Banks, current Social Services commissioner – filed a class action lawsuit against the Bloomberg administration for a right to shelter for homeless youth. The de Blasio administration inherited the suit.

Secondly, the federal government, in 2010, put forth a goal to “end youth homelessness” by 2020 and needed numbers to determine progress. In 2013 the city began asking age during HOPE, and this year the federal government will baseline the number of homeless youth across the country.

The Legal Aid complaint, filed in federal court, is based on the claim that Federal and State law requires “New York City to provide shelter – without qualification – to any homeless youth 16-20 who seeks it. It has failed to do so.” The de Blasio administration has fought tooth and nail against it.

In its fight against a right to shelter for homeless youth, administration officials commissioned an internal report examining the 2007 study (as well as other documents), which was subsequently discussed in deposition of a city official. The official found the 2007 study to have “serious methodological and data and analytic flaws” that “result in the invalidation of the results of the [2007] study.” It cast in doubt “conclusions concerning the number of homeless youth in New York City.”

Two days after the above-mentioned testimony, the de Blasio administration made a major announcement: 300 homeless youth beds would be added. De Blasio explained,

“Understandably, some young people do not feel comfortable in adult shelters. And when they did not have an alternative in terms of a youth shelter, they had to choose an adult shelter, which they may not have felt was right, or the streets, which were obviously dangerous and not right for them either. It was a horrible choice and a dangerous choice… We’re adding 300 – 300 safe, secure, dedicated beds.”

When asked, Commissioner Banks evaded offering a clear answer to how many homeless youth were in the city. De Blasio made promises about committing resources, some of which he fulfilled. Internal decisions on the city’s official perspective about how many homeless youth are in the city were just that – left to emails and meetings, largely out of public view.

A year since the announcement, the city has added a significant number of desperately needed transitional beds for homeless youth, but only successfully opened two-dozen crisis beds – that is, entry-level beds – for youth to access straight from the street.

What Could Work?

The city could take specific steps to produce an accurate estimate of homeless youth and – more importantly – provide desperately needed aid to support them. Here’s some steps that could be taken.

First, truly acknowledge the crisis of youth homelessness in New York City. Match that acknowledgment with the required resources. If another count is necessary it should be fully funded with all of the city’s coordinating power on board. It should include the empowered voices of providers and youth. It’s imperative a count occur in the warmer months. However, since the only number that counts for the federal government is generated during HOPE and immediately after, HOPE should be revamped.

Second, change the HOPE methodology. The HOPE process is where the city puts most of its resources for producing an official number of people living on the street. Though seen as a “gold standard” by HUD, it produces systematic undercounts. Research has shown that post-count surveys at service-sites find significant numbers of people living on the street and otherwise not counted. If the city were to supplement its HOPE effort with a post-count survey approach, they would likely capture a more accurate number of those living in some variation of street homelessness – including homeless youth.

Third, end the criminalization of homelessness. As a city we need to acknowledge the consequences of Mayor de Blasio’s version of criminalizing homelessness and confront it head-on. Street sweeps, move-on orders, and police efforts to get homeless people out of the subways further push already-marginalized people into hiding. They are thus less likely to be counted or seen by providers – and, most importantly, unlikely to be offered resource options.

Fourth, the city should increase its homeless youth outreach services. More youth-focused outreach workers are needed to provide linkages to homeless youth services. Youth-focused outreach workers develop expertise in locating and engaging homeless youth who are notoriously skilled at hiding to survive.

Finally, the city must increase its youth crisis beds. Transitional beds are necessary, but there is an urgent need for opening beds for youth to sleep in right off the street.

As the mayor noted in January 2016, the status quo isn’t acceptable. One can only hope the mayor’s progressive proclamations can eventually land with more homeless young people going from the streets straight into a safe and secure bed. We are not there yet.