NYC DOHMH

Part of the drop in teen pregnancy is credited to the city's aggressive public messaging campaign combined with ready availability of contraception.

“Victory has a hundred fathers

and defeat is an orphan.”

-Count Galeazzo Ciano (1903-1944)

* * * *

If rates of unplanned pregnancies in New York City had doubled since the year 2000, tabloids might then have carried headlines like: “Moral decay grips city & merry youth parties,” “Social fabric fractures as adolescents embrace,” “The American city’s unraveling – giddy teens engage chaos,” and “Public health officials clueless as teens romp.”

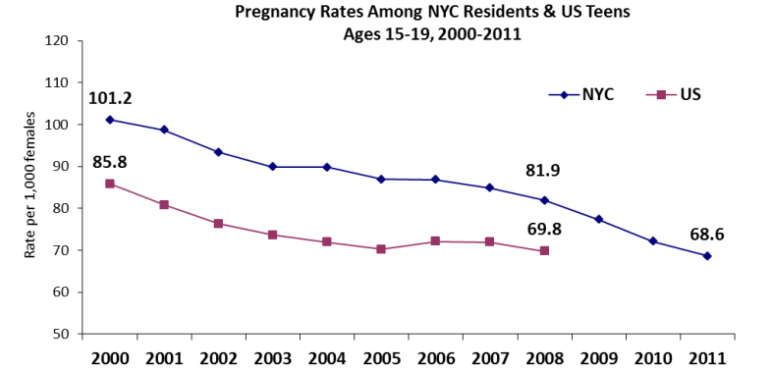

The opposite has taken place. Unplanned pregnancies in New York City are half now of what they were in the year 2000—down 57 percent in terms of raw numbers, and 53 percent when measured as a rate of birth among teens, according to the city’s Department of Health and Mental Hygiene (DOHMH).

According to the National Campaign to Prevent Teen and Unplanned Pregnancy, since its high in 1991 the teen birth rate has declined by 64 percent nationally.

The changes are no accident. A massive public health effort – involving government, schools, physicians’ organizations, community groups, foundations, parents, and youth themselves — is what’s behind the shift. Experts give credit to an array of organizations that have done much to produce this accomplishment, from federal and local health officials to schools to TV shows about teen moms to adolescent peer leaders.

That endeavor continues—in part because, in many city neighborhoods, rates of unplanned pregnancies remain much too high. “Though the teen pregnancy rate in the South Bronx has decreased, it is still nearly 50 percent higher than the citywide rate, and the vast majority of these pregnancies are unintended,” Planned Parenthood of New York City’s Director of Social Services Randi Coun tells City Limits.

The lesson, Coun says, from past success and for current efforts, is that “when young people have “the resources they need to make informed decisions about their reproductive and sexual health” then they tend to “lead empowered lives and continue to pursue their dreams.”

Explaining a drop

“At the end of the day, the credit for the declines in teen pregnancy goes to adolescents themselves, who are making an effort to prevent unintended pregnancy,” wrote Heather D. Boonstra in 2014 in the Guttmacher Policy Review. “The question now is whether society will do its part by adopting policies that support and equip young people with knowledge, skills, and services to stay healthy. The research shows that adolescents need more comprehensive education, not less, and increased access to contraceptive services, not less. To argue anything else misses an opportunity to sustain these trends.”

Examining the large decline in teen birth rates nationally, Cora Collette Breuner of the American Academy of Pediatrics’ (AAP) Committee on Adolescence “attributes the overall decline in teen birth rates to increased use of contraception.” A 2016 analysis in the New England Journal of Medicine by Lawrence B. Finer and Mia R. Zolna finds the likely explanation for the decline in the rate of unintended pregnancy nationally “is a change in the frequency and type of contraceptive use over time.”

And in the Journal of Adolescent Health, Laura Lindberg, John Santelli and Sheila Dessai also conclude that “improvements in contraceptive use appear to be the primary proximal determinants of declines in adolescent pregnancy and birth rates in the United States from 2007 to 2012.”

Further, the research demonstrates that “increasing use of abortion has not contributed to these declines” in the adolescent birth rate,” Lindberg and colleagues found. “In fact, the ratio of abortions to live births have been declining.”

Teens didn’t make those shifts unassisted. In New York, the high school Condom Availability Program, which is required in all high schools, offers students free condoms, health information and health referrals provided by trained staff.

Evidence suggests that reality television programs such as “16 and Pregnant” and “Teen Mom” may also have influenced teen birthrates in recent years, explains Boonstra. She points to a study that found that close to the time new episodes of these shows appeared Internet search activity and tweets about sex, birth control and abortion increased to a substantial degree.

There have also been New York City bus and subway ads, texting and social media campaigns, public health announcements, and YouTube videos. The city’s Human Resources Administration/Department of Social Services has used ads showing a baby saying, “Honestly, mom … chances are he won’t stay with you. What happens to me?” And city government’s teen website incorporates information on pregnancy prevention.

The Office of School Health, a joint program of the New York City Department of Education and DOHMH, now partners with 62 school-based health centers providing primary care and reproductive health services, says Deborah Kaplan, assistant commissioner of NYC’s Bureau of Maternal, Infant and Reproductive Health. These serve around 90,000 students and are “primarily located in areas with limited access to health care services,” according to schools.nyc.gov. Notably, these services are confidential.

As part of the program, teens are taken in group visits to local community health centers “to break down the mystique of what happens when you go to a clinic” and to make teens “feel comfortable going to a clinic,” Kaplan said, while expressing the hope that teens will use these community health centers for general l health needs, as well. The school-based program, together with the Connecting Adolescents to Comprehensive Health (CATCH) program “reach about half of NYC public high school students,” Kaplan says. CATCH is a program of the NYC Health Department’s Office of School Health (OSH ). The CATCH program offers a range of contraceptive methods as well as pregnancy testing, patient-centered contraceptive counseling, and referrals to community-based health centers, which themselves provide more comprehensive services. As of June 2016, the CATCH program was at 40 high school campuses, so that CATCH sites served 55,560 high school students.

DOHMH

Meanwhile, the evidence-based sex ed curriculum, Reducing the Risk, is recommended by the Department of Education citywide for high schoolers. It “focuses on helping students develop the skills necessary to care for themselves, access reproductive health services, set and achieve their goals, and make healthy choices,” according to the health department.

The city requires that sexual health lessons be included in middle and high school health education courses. That work goes beyond what state guidelines demand: New York State does not have a specific sex education requirement, though it does have a health education requirement and does require HIV/AIDS instruction for every student, every year.

According to a 2014 report by Nan Astone, Steven Martin, and Lina Breslav for the Urban Institute, current data indicates that “the provision of comprehensive sex education and reproductive health services can increase the use of effective contraception without promoting sexual activity.” In addition, the American Academy of Pediatrics says, “Research has conclusively demonstrated that programs promoting abstinence only until heterosexual marriage occurs are ineffective.”

Simultaneously, Planned Parenthood of New York City (PPNYC) has been conducting a range of programs aimed to decrease sexual risk behaviors, including the reduction of unintended pregnancies for teens and youth. These evidence–based programs target young people ages 11 through 19 and work through schools, after-school programs, and community organizations with special focus on “high-risk communities” in Brooklyn, The Bronx, Manhattan, and Queens. Other PPNYC programs in Brooklyn, the South Bronx, Manhattan’s Lower East Side rely, in part, on trained teen educators.

Credit goes as well to such organizations as The National Campaign to Prevent Teen and Unplanned Pregnancy (and its websites Bedsider and StayTeen) the Reproductive Health Access Project; and Advocates for Youth The American College of Obstetrics and Gynecology (ACOG) also provides a website for teens on birth control.

And some credit goes to parents. According to the American Academy of Pediatrics, a review of studies found that parents who went for training on how to talk with their adolescents about sex achieved better communication with their teens about sexuality, delay in sexual debut, and increased use of contraception and condoms.

Many additional factors are relevant, some local, some national, Boonstra’s analysis indicates. These include the impact of AIDS education programs, the increase in the proportion of teens with medical insurance following the implementation of the Affordable Care Act, the availability of the Internet as a source of health information (including the kind a teen might be afraid to ask an adult about directly) and the continued availability of family planning centers that offer confidentiality.

Gaps remain

Despite the progress, “the United States continues to lead industrialized countries with the highest rates of adolescent pregnancy,” according to the American Academy of Pediatrics. And some groups experience the issue much more intensely than others.

According to the Guttmacher Institute, nationwide data shows that although rates of teen pregnancy and its outcomes have declined among all racial and ethnic groups, wide disparities persist. In 2011, pregnancy rates among non-Latino Black teens (92.6 per 1,000) and Latino teens (73.5 per 1,000) were more than double the pregnancy rate for non-Latino white teens (35.3 per 1,000). These disparities mirror those found among all U.S. women of reproductive age.

The 2016 New England Journal of Medicine article explains that nationally “although the differences in rates of unintended pregnancy across demographic groups narrowed over time, large disparities were still present in 2011. In particular, poor, black, and Latino women and girls continued to have much higher rates of unintended pregnancy than did whites and those with higher incomes. Much more progress can be made in eliminating these disparities.”

The disparities are clear locally, too. According to a 2014 Urban Institute report, in New York City pregnancy rates between the years 2000 and 2011 per 1,000 female residents ages 15 to 19 declined from 147.4 to 101.7 for Blacks, 132.2 to 82.0 for Latinos, 32.6 to 15.5 for Asian and Pacific Islanders, and 28.6 to 19.6 for White non-Latino women. (Notably, these rates show all pregnancies for women of these ages, and some of these pregnancies probably were planned and welcomed.)

Rates of pregnancy also differed by borough. For 1,000 female residents ages 15 to 19, pregnancy rates between the years 2000 and 2011 went from 139.5 to 95.1 in the Bronx, 104.4 to 69.6 in Brooklyn, 98.9 to 62.8 in Manhattan, 88.4 to 55.3 in Queens, and 59.7 and 40.8 in Staten Island, according to UI.

Looked at another way, “Preventing unintended pregnancy is more difficult for women with the least resources: among women who gave birth in 2011, 46 percent of those in the lowest-income households (<$10,000) reported that their pregnancy was unintended, compared with 20 percent of women in the highest-income (>$75,000) households,” according to DOHMH.

Those disparities have a social impact. A 2012 study by Lisa Shuger of The National Campaign to Prevent Teen and Unplanned Pregnancy concluded that close to one-third of teen girls who have dropped out of high school cite early pregnancy or parenthood as a key reason. This research also found that only 40 percent of teen moms finish high school.

Further, the health of both the newborn and the future mom is more likely to be in jeopardy in an unplanned pregnancy. Writing earlier in 2016 in the New England Journal of Medicine, Finer and Zolna explain, “Women and girls who have unintended pregnancies that result in births are more likely than those who intended to become pregnant to have inadequate or a delayed initiation of prenatal care, to smoke and drink during pregnancy, and to have premature and low-birth-weight infants; they are also less likely to breast-feed. Increased risks of physical and mental health problems have also been reported in children of women who have unplanned pregnancies.”

The next phase

Some doctors believe that for declines to continue, specific kinds of contraception will have to get wider use. Physicians of the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (ACOG) argue that “long-acting reversible contraception (LARC)—intrauterine devices and the contraceptive implant—are safe and appropriate contraceptive methods for most women and adolescents;” and that an intrauterine device, or IUD, “should be offered as first-line contraceptive options for sexually active adolescents,” while continuing to recommend that condoms be used to decrease the risk of acquiring sexually transmitted infections. ACOG explains that IUDs are far more effective than other contraceptive approaches.

During an interview with City Limits, Kaplan repeatedly spoke of “sexual and reproductive justice.” The ad seen at right is part of this campaign: which DOHMH said in 2015 was intended to “spark a citywide dialogue around sexual and reproductive health justice – which promotes individual choice and body autonomy within the context of our nation’s history of reproductive oppression and coercion directed at women of color and low-income women. The reproductive justice framework states that every woman has the right to: decide if and when she will have a child and the conditions under which she will give birth; decide if she will not have a child and her options for preventing or ending a pregnancy; parent the child(ren) she has with the necessary social supports in safe environments and healthy communities, and without threat of violence.”

“Our focus has been to work overall on health equity, and how the ZIP code you live in should not determine your health outcome,” Kaplan explained. “We have concentrated resources in communities that have some of the greatest social and economic challenges: the South Bronx, North and Central Brooklyn, and East and Central Harlem.”

“We are focusing efforts in these communities to really narrow the gap. We are looking holistically at what makes a healthy community, and particular issues like pregnancy are part of a broader picture of people having healthy neighborhoods. For decent housing, good education, safe neighborhoods – all these inform the decisions we make in our lives,” Kaplan said. “And we would like to narrow the gaps we see by race, ethnicity, and socioeconomic status.”

For instance, the Bronx Teens Connection, a successful program founded upon successful studies that generated evidence about what works in real-life situations, was recently expanded to include Brooklyn and Staten Island, as well. Initiated and supported by the CDC, the federal Office of Adolescent Health (OAH), and the Office of Population Affairs, the program was coordinated by the NYC Department of Health and Mental Hygiene, and involved the NYC Department of Education, the Administration for Children’s Services, the Department of Youth and Community Development, and the Center for Court Innovation. It focused on communities with the highest rates of teen pregnancy and on reaching African American and Latino young people aged 15 to 19 years. — And it combined school-based education, school-based clinics, additional local clinics, community partners and community education, and a Youth Leadership Team.

The Nurse-Family Partnership home-visiting program includes counseling for first-time mothers who want to achieve control over future pregnancies.

To some degree the reductions in teen pregnancy so far have been the easiest to achieve. “Financial strain and cultural barriers among low-income communities create barriers to accessing sexual and reproductive health information and services,” Planned Parenthood’s Coun explained. So, it is unsurprising that “teen pregnancy rates have remained high in underserved areas that face the most significant barriers to accessing sexual and reproductive health information and services.”

And it is important to keep in mind that “rates of unintended pregnancy are highest among 18-25 year olds” while “nationwide, women in their 20s account for 54 percent of unintended pregnancies,” Planned Parenthood’s Coun points out. “This illustrates the need for sexual and reproductive services not only for adolescents, but for people of all ages.”

6 thoughts on “NYC’s Drop in Teen Pregnancy Has a Thousand Fathers (and Mothers)”

Pingback: At Risk Youth Jobs In Nyc

Pingback: Pregnancy Websites For Moms To Be | Treatment Options for Infertility

Pingback: Teen Pregnancy Rates In The Usa | Treatment Options for Infertility

Pingback: Teen Pregnancy Rates In The Us In 2012 | Treatment Options for Infertility

Pingback: Teen Pregnancy Rates In The Us Graphic | Treatment Options for Infertility

Nice article!