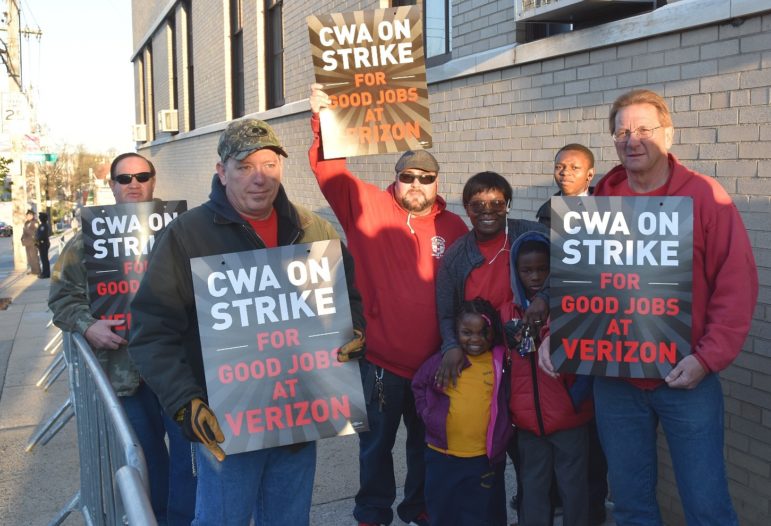

Thomas Altfather Good

On the picket line.

After 44 days on strike, 39,000 members of the Communications Workers of America and International Brotherhood of Electrical Workers marched back into work at Verizon last week having beaten back most of the company’s demands and won a foothold in organizing wireless workers. The success of the biggest U.S. strike in 5 years is cause for celebration. It’s too soon to trumpet the resurgence of the strike or the labor movement, but there’s a lot to learn to strengthen other fights.

No Backspace is City Limits' new blog featuring a recurring cast of opinion writers passionate about New York people, policies and politics. Click here to read more..

The 2011 Verizon strike came before Occupy, before “We are the 99 percent” and before the Fight for 15 transformed the minimum wage debate amid one-day strikes outside fast-food locations. When that job action started, we weren’t days away from a contested New York Democratic presidential primary fueled by outrage over economic inequality and corporate dominance that brought the candidates onto the picket line. This time around, Verizon was less able to stoke resentment of strikers’ decent paying jobs with benefits or distract attention from the CEO’s $18 million paycheck and the company’s nearly $18 billion in profits last year.

But the change in climate isn’t the whole story. In multiple ways, the workers took on the company along the contested front between the new and old economy, and won. It’s easy to look at a strike of unionized phone company workers and see the old economy. That’s certainly how Verizon has behaved, using wireless and technology to shed responsibility like so many companies in the “new” Uber and gig economy. This strike highlighted how arbitrary and blurry the line between new and old is for employers and workers.

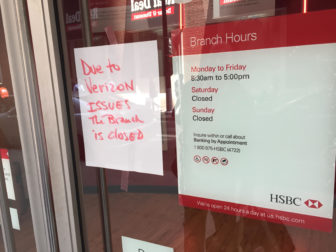

Bill Henning

A clear sign of the strike's effects.

The strike made clear that “Who built the network? We built the network” was more than a picket line chant; it was a statement of fact. As the strike wore on, the company was not able to complete repairs and installations using business-school managers and ill-trained scabs. Nor could it keep up installation of FiOs, already a sore spot in New York and many other cities for ongoing delays in its expansion. Verizon underestimated the importance of its workforce: the costs of delays and service failures mounted, impacting its customers and its reputation.

Retail, banking, medicine and the whole virtual internet-app-cloud economy all rely on a broadband, cable, and internet infrastructure that’s physical, and requires workers, investment, and maintenance to function. That’s a message that is often lost in the noise of the new economy but is crucial to empowering and connecting workers, as well as involving communities in demanding oversight, regulation, and investment.

Another battleground was over Verizon’s demand to be able to send workers far away from home for months on end without choice, and without regard to the impact on families, caregivers, and lives. Like retail workers facing just-in-time scheduling and erratic shifts, these were employees – not contractors – facing the bosses’ use of flexibility as a weapon. Verizon made clear it’s not only the app economy that’s looking to come as close as it can to an on-demand workforce that uses the minimum number of workers and pays them only exactly when and where they are wanted for as little time and cost as possible.

And, while the unions have been resisting off-shoring and outsourcing for years, this strike put the issue at the forefront. On both these fronts, workers won protection against Verizon’s push to put stable union jobs onto the slippery slope into contingent and precarious work.

More than in the past, the strike confronted the erosion of stable work by taking on Verizon Wireless. Wireless has grown enormously over the last 15 years to make up the lion’s share of company revenues and profits. Verizon Wireless stores are staffed by workers making far lower wages and benefits than Verizon union members and subject to the precariousness of the non-union, heavily part-time retail economy. For the first time, Verizon Wireless retail workers in Brooklyn and Massachusetts struck along with the rest of the workforce, winning a contract after voting to unionize in 2014. The number of unionized retail Verizon wireless workers is small, but a signed union contract is a real foothold to grow from in the company’s growing and most profitable sector.

The unions also made strong strategic use of Verizon’s retail visibility to put pressure on the company. This wasn’t the first time that the stores were the site of union activity – after ending the strike five years ago without a contract, workers held regular actions outside stores. This time, there were daily strike picket lines at the retail outlets where the public encounters Verizon – rather than at unnoticed phone company offices. National actions outside of retail wireless stores, like the dispersed actions that have characterized the fast-food Fight for 15, channeled increased solidarity activity and participation to confront Verizon far beyond the footprint of the strike.

All of it added up to Verizon facing real economic losses by the time the settlement was reached, with Wall Street projecting a $200 million impact on profits. One article quoted a shop steward saying, “My gut feeling is that it’s a defensive victory, with a couple of exciting potential advances.” So from a cautious optimism, now it’s time to build on the advances, and to hear more, especially from strikers and their unions, about what was and wasn’t done, and what the impact is. How can we learn from the strike and build new fights in the wide space where the new and old economies meet?

Katie Unger is the daughter of a recently retired CWA member and officer, and walked my first phone company picket line in 1983. An independent strategic consultant and fourth-generation New York labor activist, she has spent more than a decade developing organizing campaigns in the fast-food, laundry and other industries. Katie recently served the City of New York working with communities on progressive policies as a Deputy Commissioner of the Mayor’s Community Affairs Unit. @KungerNYC