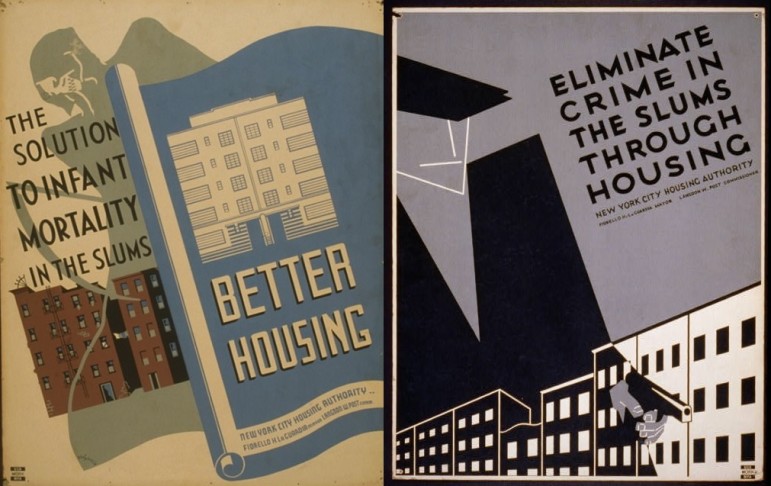

WPA-Library of Congress

Public housing came closer to the hopes of the 1930s in New York City than elsewhere, but problems of physical isolation and complex questions about which income groups belong there continue to shape NYCHA.

Most public housing residents have probably heard of “NextGeneration NYCHA,” the ten-year strategic plan that drives the De Blasio administration’s public housing agenda. But what exactly makes today’s vision for public housing so different?

It’s all about public-private partnerships, according to NYCHA Chair Shola Olatoye and the other panelists at “The Next 100 Years of Affordable Housing,” a discussion at Cooper Union on Wednesday night hosted by Matthew Gordon Lasner and Nicholas Dagen Bloom, authors of “Affordable Housing in New York.” Every aspect of public housing—how it’s funded, service delivery, architectural design—depends on collaboration with the private sector and integration with the world beyond the towers.

“There is no Washington fairy coming,” said Olatoye. “The salvation of public housing lies in the fact that we get more than the ‘housers’ to care about it. That is part of the public-private model.”

There is a widespread perception that the public housing model failed because it packed large numbers of low-income people in tall, ugly buildings, isolating them from the general population. Wednesday night’s panelists offered a more nuanced take: the problem wasn’t the architecture so much as the social marginalization of residents and their dependency on a federal funding stream that has all but evaporated. Public housing visionaries must strive for community integration not by tearing down the towers, as other cities have done, but by finding financial and social resources beyond hamstrung Congress.

According to Olatoye, that is the philosophy driving a host of the authority’s initiatives, from the controversial infill development program, which will generate funds by allowing private developers to build on NYCHA land, to the Rental Assistance Demonstration (RAD) program, which converts public housing to Project Section 8 developments to leverage private investment.

Mayor de Blasio has also taken steps to delegate some of NYCHA’s responsibilities to other public and private organizations. He shifted NYCHA’s annual $70 million payment for policing to the NYPD, while other city agencies have taken over some of NYCHA’s community and senior centers. The authority is also working with workforce providers and other nonprofits to provide economic opportunities for NYCHA residents.

The architects on the panel emphasized the importance of preserving public housing towers while also improving their integration with the rest of the neighborhood. On a projector screen, panelist Alexander Gorlin, an affordable housing architect, shared layout designs for a future, utopic Brownsville Houses, with the towers woven seamlessly with urban agriculture, solar and wind farms, and commercial strips.

“Ultimately, public housing is as much a matter of site plans as it is of facades, and there has been far too much focus on facades,” said panelist Gwendolyn Wright, an architecture, history and art history professor at Columbia. She said the real question should be, “How can we use everything from agriculture to street systems to connect the public housing to the surroundings?”

Yet for all the promise of this new focus on integration, working with the private sector to provide essential services carries dangers: it means taxpayer dollars will also engender private profit. According to panelist Joseph Heathcott, an urban studies professor at the New School, ensuring that public money is spent wisely is a key challenge for the coming century.

“Is the public money that we’re spending on public housing just going to disappear into the marketplace or is at actually going to create permanent public housing?” Heathcott asked. In other words, can policymakers develop “subsidy recapture mechanisms” to ensure successful affordable housing developers don’t simply line their pockets. (Those mechanisms have in other settings included clawbacks if subsidized properties are sold, equity sharing and more.)

During the question and answer session, an audience member put it more bluntly: “Why do we want to privatize public housing?” he asked. Olatoye responded that pursuing “public-private partnerships” is “a pragmatic approach to ensuring that we have a sustainable operating source for these buildings.”

If taxpayers want to avoid a complete privatization of the provision of public services, then government needs increased funding—and that requires another kind of public-private partnership: between public housing residents and taxpayers of all income levels and backgrounds. “NYCHA is a treasure that everyone should come to embrace,” said Heathcott. “Our job, all of us, is to make it politically possible for you to do your job,” he said to Olatoye.

The first generation of public housing enjoyed this kind of widespread public support: in the 1930s, policy makers and housing advocates imagined public housing would shelter the middle class, too. In the 1940s, developers, fearful of a diminished housing market, lobbied to include income restrictions to ensure the government only provided housing for the poorest.

Will the nation ever return to that earlier conception of public housing? Perhaps in today’s post-Recession economic climate, with Americans feeling the squeeze of the housing market, the public will once again see public housing not as an urban scourge, but as a vital public resource that should be available to many.

“People need it all over the country,” said Wright. “What becomes crucial is to break the idea that it’s for people who are failures.”