When Mayor de Blasio arrived in Albany on Tuesday, he had a lot to talk about: aid to CUNY, cost-sharing for Medicaid, mayoral control of the schools and more. Instead, upstate lawmakers wanted to talk about a property tax cap. New York City is the only place in the state that doesn’t have one, and apparently that irks Republicans.

The property tax is one of the few revenue lines that the city controls on its own. If it wants to raise other taxes, like the income tax, it has to go to Albany for approval. That fact is probably not unrelated to the push to get the mayor to surrender his authority to raise the property levy.

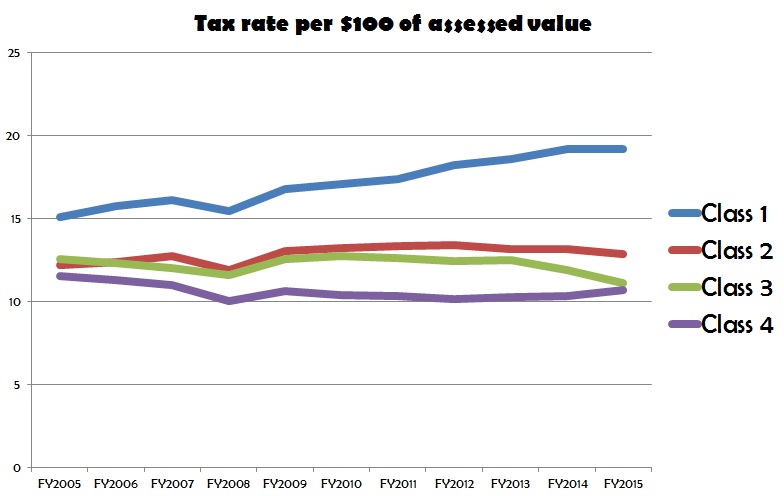

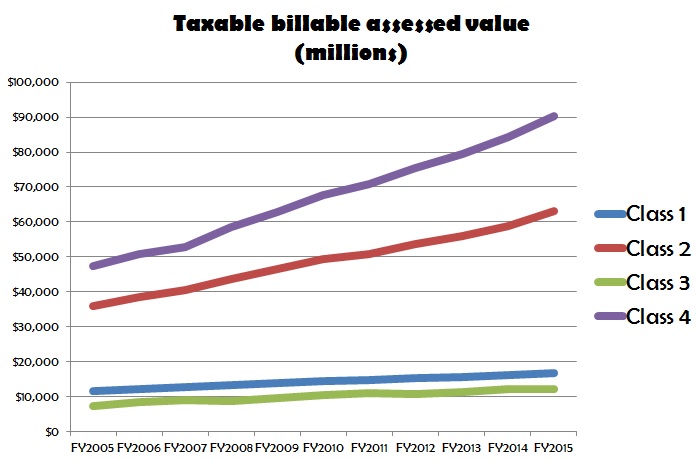

The property tax accounts for about 40 percent of the city’s revenue each year, twice as much as the personal income tax (about 20 percent) or sales tax (roughly 14 percent). Mayor Bloomberg oversaw a significant increase to close the post September 11 budget gap, a move that hurt his first-term popularity a lot. As the chart above indicates, growth in the tax rate has been modest; it actually dropped last year on “class 1” properties. Since property tax revenue grows with property values, those numbers (in the chart below) rise a little more, especially for some classes of properties.

There are certainly elements of the property tax that might be improved. Hoping to spur low-income housing production, some have called for changes to how vacant or unused property is taxed. Others have highlighted disparities in how different properties are taxed. And, of course, there’s the ongoing debate about the value and fairness of 421-a, a property-tax break.

But the numbers above and below don’t seem to scream out for a property-tax cap—however useful the topic might be for people who’d rather not talk about the city’s actual needs.

(Class One is primarily one-, two-, and three-family homes; Class Two is all other residential property; Class Three is owned by utility companies and Class Four is all other commercial property.)

2 thoughts on “The Numbers on NYC’s Property Tax Non-Problem”

Good post; no disagreement with the substance.

But.

What’s missed is real estate tax rates are merely one aspect of calculating real estate taxes. The tax rate is multiplied by the “taxable value” which in turn is affected by the “exemption value” (if any), the “transitional assessed value”, the “actual assessed value”, the “assessment percentage”, and (Are you still with me?) the “market value”. Chico selling Groucho the Code Book, the Master Code Book and the Breeder’s Guide in “Day at the Races” may have inspired this arrangement.

In many NY jurisdictions outside NYC, the “taxable value” is a whole lot closer to real-world numbers. In NYC, the “taxable value” is utter fiction.

If the state actually were to cap NYC’s property tax rate, I’ve heard / read no mention of whether “taxable value” of NYC real estate would be calculated differently. Cutting to the chase, property tax rates could be capped, but adjusting the value that’s taxed could result in essentially unchanged real estate tax bills.

Whether real estate taxes are “equitable” is an excellent subject for discussion, but merely addressing tax rates is ignoring all the other aspects of how real estate taxes are calculated.

The State tax cap applies to the levy, not the rate or assessed value per se, but rather the result of applying one against the other. The latest budget projection from the Mayor’s office shows taxes on class 2, multifamily, going up 7.8 percent in fiscal 2017–pretty much what it has been doing every year for a decade despite “no tax increase.” The net effect is that property taxes in New York consume about one third of gross rents–something that is completely incompatible with providing affordable housing. So, yes, taxes are an issue.