CASA

Photographer Rhynna Santos, HPD Commissioner Vicki Been and CASA tenant leader Fitzroy Christian at Sunday's panel.

There was a packed house at the gentrification conference last Sunday sponsored by City Limits, the Bronx Documentary Center and New Settlement’s Community Action for Safe Apartments, or CASA. The questions to the panel including the commissioner of the Department of Housing Preservation and Development, Vicki Been, were many and pointed.

When time ran out, it was suggested that questioners who never got a chance at the mic should email their questions in. One such email asked the following: “Isn’t the Jerome Avenue proposal and similar ones under the de Blasio rezoning plan, a recipe for destruction and mass murder?”

That’s pretty extreme, and not reflective of the thoughtful and reasonable (though, yes, passionate) tone of most of the questions directed at Been and her co-panelists: Vivian Vazquez, an educator who is working on a film about the Bronx’s fall and rise; Rhynna Santos, a photographer associated with the remarkable Jerome Avenue Workers Project; and Fitzroy Christian, a CASA tenant leader.

Most of the skeptics steered well clear of paranoia; they asked about NYCHA, schools, community preferences and rent levels in affordable apartments. Yet all of the questioners expressed not just misgivings about particular details of the de Blasio administration’s housing and rezoning plans, but a deep lack of trust.

Take the administration’s spending on legal assistance to protect tenants from harassment and eviction: Been boasted of that effort as a signal of the mayor’s commitment to preserve affordability. But Christian depicted it as a tacit admission that City Hall expects a wave of harassment and evictions triggered by the planned rezonings to sweep the city.

The distrust extends to the very premise for the housing plan—that market forces are reshaping the city and New Yorkers must respond with policies that make the best of a bad situation—which skeptics say ignores the impact of mayors before de Blasio.

“What happened in Park Slope, what happened in Williamsburg, what happened on the Lower East Side, East Harlem, Red hook, was socially engineered change,” Christian told the crowd. “The administration wanted it to happen and they changed the laws to make it happen.”

De Blasio’s doubters also question the notion that the private sector must be enticed to build. “It is not true that you need to incentivize these billionaires,” Christian added. “They will build where they want to build so long as the law allows them to build, and there’s no need for our tax dollars to go to their profit margins and we get nothing in return.”

Besides the concern that public resources like tax abatements were going to support market-rate housing, skeptics noted that “affordable” housing built for people at, say, 60 percent of area median income (AMI) could be unaffordable to area residents.

Been tried on Sunday to rebut the notion that the housing plan supports housing that’s out of reach to people in the Jerome Avenue area.

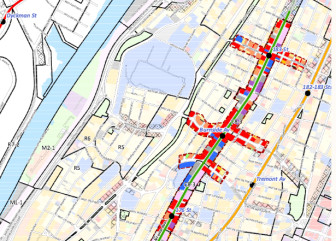

DCP

'If the administration is truly open to community input, the report released in October by the Bronx Coalition for a Community Vision gives planners much to chew on.'

“I am not subsidizing market-rate housing. I am subsidizing affordable housing. The tax abatements are requiring affordable housing. That was a major victory that we won in the state legislature last year to make sure that nobody gets a tax abatement who isn’t providing affordable housing,” she said, referring to changes to the 421-a program.

She added: “When we talk about the 60 percent AMI housing, that is what the federal low income housing tax credit targets. We go much lower, down to 30 percent AMI, and that is a discussion that we want to have with the community about what the income target should be, how much should be at different incomes, et cetera. That is a conversation that is underway and we look forward to having that. It requires money. And that is the question is, what can we require of the developers and then how much can that free up subsidy dollars that we can spend to target the 30 percent AMI units. That is exactly the conversation that is underway.”

At one point the commissioner was asked about rezonings occurring under the radar. The administration has stressed that the plan for Jerome Avenue is “very much a work in progress,” as Been put it. Same goes for the rest of the city where, she insisted, only two rezonings have actually been announced—East New York and Jerome Avenue—with other areas still earlier in the process. “I just want to allay the fear that there are a lot of rezonings out there that are under the radar. There are not. Nothing is unannounced. And the work on where exactly there is capacity is all underway.”

The de Blasio administration has pointed to a civic engagement process around the rezonings that is much more extensive than anything the Bloomberg team, which rezoned a vast portion of the city’s land area, attempted. But the administration’s priorities—to increase residential density in the areas it is targeting through allowing more market-rate development and financing affordable housing—were largely set ahead of time, and that’s made some community members suspicious of how much a role their input is playing.

The misgivings, however, are about much more than Bill de Blasio’s communications strategy.

“What is going on here in New York City it is a war,” said one young man as Sunday’s panel wrapped up. “They are fighting a war against poor people: Poor, working class black Latino Muslim people. There are refugees coming from Brooklyn. Here in the Bronx is where we can make a stand.”

One thought on “De Blasio Housing Plan Hung Up as Much on Distrust as on Details”

Refugees coming from Brooklyn…. this is totally horrible. This so-called housing plan is a cover story for real estate speculation… Yes the “market” portion will include condominiums… where no one will live most of the year. And that is the 70-80% of these so-called affordable buildings…. really is Glass-Steagall Act of 1933 reorganization of the bankrupt financial system or die… http://www.larouchepac.com has the recipe, if you want to survive, that is…