Adi Talwar

A freegan who goes by the name of 'Smiley' at the end of more than three hours of dumpster diving that spanned from 51st to 86th Street and Park to 1st Avenue.

Trash may not be treasure, but it can be groceries.

The United States Department of Agriculture and Environmental Protection Agency announced plans this year to halve food waste by 2030, but dumpster divers—also known as freegans—have been eating away at food waste for decades.

Freegans crouch on the sidewalk, unknot trash bags and pull out produce, frozen foods, bread and more. They can skip the checkout lines at bodegas and ignore the price stickers at Trader Joe’s and Whole Foods; they get their food for free by scavenging through the garbage dumped by stores, restaurants and hotels.

A group meets bi-monthly for a trash tour through New York City neighborhoods. A crowd of about two dozen people meet up—tote bags, wheelie suitcases and shopping bags in hand—and together hit up the garbage piles of grocery stores, restaurants and drug stores.

“With patience, everything I need I can find in the garbage,” says freegan Janet Kalish, 52.

Kalish, a former high school Spanish teacher who lives in Richmond Hill, was bitten by the freegan bug in 2004. She went dumpster diving with a group of environmental activists one night after getting an email about an upcoming trash tour.

Kalish was apprehensive at first, but now she buys almost nothing—just cat food, cat litter and toilet paper.

Freeganism has its basis in a mix of ideologies including a desire to fight consumerism and a push for environmental justice. But some freegans dumpster dive for food simply because they don’t have the money to afford meals.

The practice dates back to the 1600s when Gerrard Winstanley, a British cloth seller, formed a community that farmed for free in England. He abhorred waste and wrote extensively about his views, calling the world “a common treasury for all, both rich and poor.”

In 1960s San Francisco, a group of radicals called the Diggers picked up on Winstanley’s ideologies and planted the contemporary seed of freeganism. The Diggers set up stores of free food. The food they gave away was scavenged from the trash, harvested from their gardens, or stolen.

Their work has led to modern day freegans, like dumpster diver Mike Williams, 49. When Williams started about six years ago, he felt like everyone was staring at him. He thought the police would get involved as he rifled through trash bags for his groceries.

“It was going to be like a sideshow,” Williams says. “Everyone was going to notice what I was doing.”

The anxiety is common among newbie freegans, but many stick it out and do their part, however small, in cutting down on the trash sent to landfills.

Composting in Gowanus from Aliza Chasan on Vimeo.

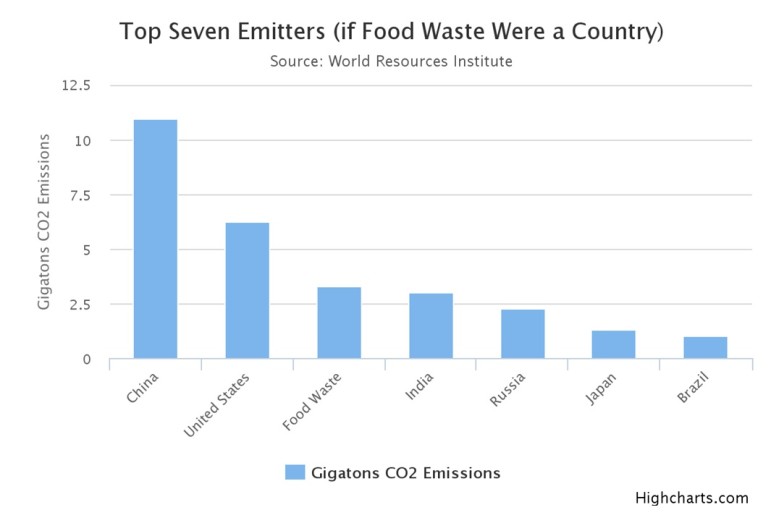

Tossing withered carrots, bruised apples and half-eaten lasagna into trash bins contributes to global warming. As organic trash rots away in landfills, it releases methane, a dangerous greenhouse gas.

Landfills are one of the largest sources of methane emissions in the U.S. and the majority of the dangerous gas is a byproduct of rotting food, according to the EPA. Breakfast, lunch and dinner are served up daily with a side of climate change.

Less than 50 percent of methane emissions from landfills can be captured, according to Nickolas Themelis, director of the Earth Engineering Center at Columbia University. The rest contributes to global warming. Methane has 21 times the global warming potential of carbon dioxide, according to the EPA. Landfills account for 20 percent of all methane emissions in the U.S.

Aliza Chasan

Organics that break down in landfills undergo anaerobic digestion, which means the food isn’t exposed to oxygen as it decomposes, so it produces methane. Compost piles are turned and agitated to expose the waste to oxygen, so the decomposing waste there produces carbon dioxide instead of minimal methane.

But many people don’t compost because of the smell, Themelis says. In New York City, many people also don’t compost because they think that compost bins attract rats, according to Caroline Bragdon, a research scientist with the city Health Department’s division of veterinary and pest control services. That isn’t the case at all, Bragdon said at an Upper West Side waste forum on Nov. 10.

The brown bins the city has for composting are locked and impenetrable to animals. Using them can actually cut down on pests who can more easily chew through garbage bags or get into regular garbage cans.

Households not in the pilot areas can collect their own compost and bring it to collection sites around the city. Residents of 10-plus unit apartment buildings can also request organics collection for their building.

Composting levels also aren’t as high as they could be because the high cost of capital investment in large-scale anaerobic digestion facilities, which degrade organic waste into nutrient-rich soil, means there aren’t many of these facilities, Themelis says.

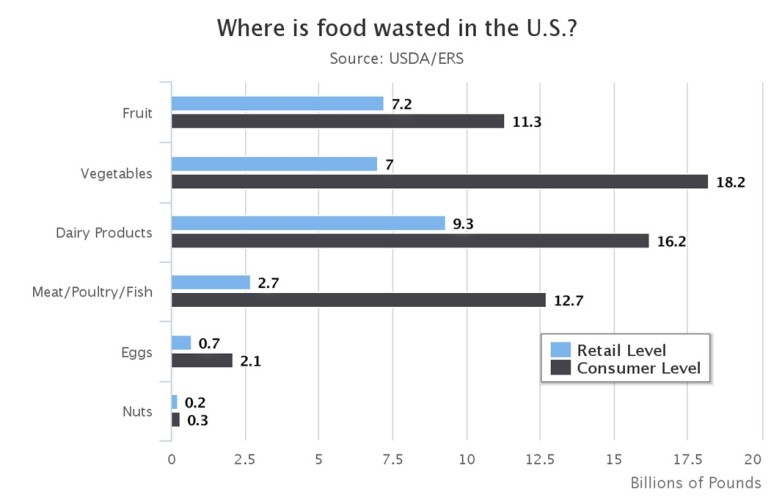

Food waste also has an immense economic cost. The average person in the U.S. spends $522 a year on food he or she never eats, according to the USDA. That’s about a month’s worth of groceries per person thrown straight into the trash.

Not everyone can afford that. Williams got into dumpster diving as a way to save money.

He lives in Queens now and goes out grocery shopping through the waste in Manhattan two or three nights a week; Freegans say Manhattan is the best borough for finding food waste because densely populated neighborhoods have lots of stores.

Aliza Chasan

When Williams started, he lived in New Jersey and commuted into the city to dumpster dive.

“I had a mortgage and I was trying to hang onto the house,” Williams says. “The mortgage took up everything that I made so I was trying to find a way to try to get by without buying food and other things that I might need.”

Most people don’t feel comfortable dumpster diving though, even if they’re in financial straits, Kalish says.

“We grow up learning about garbage being dirty and dirty meaning germs and germs meaning illness and it’s not considered safe or healthy.” Kalish says. “It’s not considered mannered or educated or civilized to a lot of people.”

Globally, one in nine people goes hungry every day, according to the United Nations. In America, 14 percent of the population lived in food-insecure households last year, which means they didn’t have access to enough nutritious food for a healthy lifestyle, according to the USDA.

Just 15 percent of the annual food waste in America could feed 25 million people, according to the Natural Resources Defense Council.

“It’s just outrageous when I see piles and piles, bags full of good food,” Kalish says. “It’s a mess that we have a lot of people who are unable to eat well while food is being wasted. It just doesn’t make sense.”

Some grocery stores don’t donate food because they’re concerned about food health and safety issues and potential lawsuits if donated food makes people sick. But there’s actually a federal law that would protect them—the Bill Emerson Good Samaritan Food Donation Act.

People and stores who donate food to a charity are not subject to “civil or criminal liability arising from the nature, age, packaging or condition of apparently wholesome food” if they make the donation in good faith.

Some companies also don’t donate because it costs money to package, store and deliver food to non-profits.

Aliza Chasan

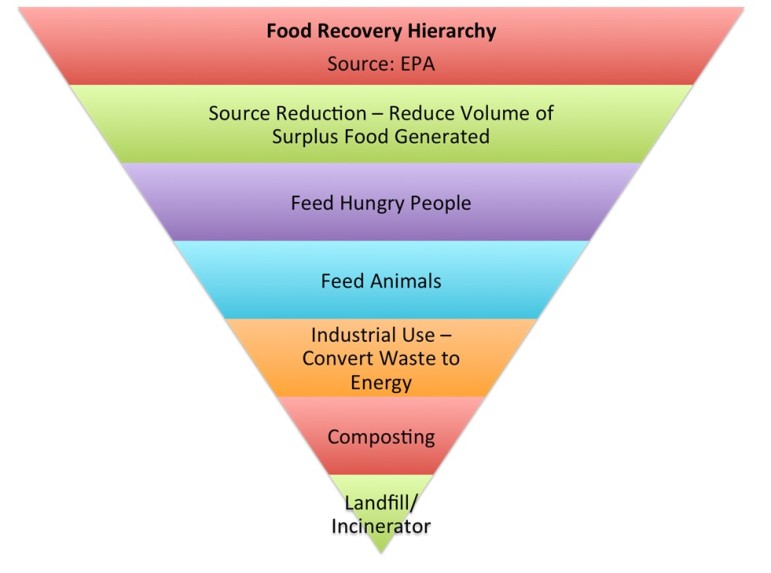

Many big chains like Walmart, Albertsons and Safeway now donate, according to Joel Berg, director of the New York City Coalition Against Hunger. But while the outlook for hungry people is pretty bleak, capturing food waste isn’t necessarily the way to fix it, he says.

“Food waste is really important for the environment, but can only marginally help at the edges in reducing hunger,” Berg says.

The idea that low-income people can survive on other people’s garbage is wrong, Berg says. Many who deal with hunger and malnutrition have compromised immune systems and because of that, the food they eat needs to be extremely safe and healthy. The cost of ensuring food safety while minimizing waste may actually exceed the cost of buying new food.

There is more that can be done to capture food waste though, particularly on the farm level, Berg says.

Part of society’s potential food supply is lost before a store or consumer has a chance to waste it. Food loss starts on the farm where edible food is sometimes rendered useless because of things like mold, pests like rats and bugs or poor refrigeration. This is a major problem in developing countries, but a much smaller problem in America where the main issue is food waste.

Food waste starts when food isn’t eaten or even sold because it’s considered ugly. Right now, only the most aesthetically pleasing produce makes it to store bins and shelves. About six billion pounds of edible, ugly produce gets trashed each year in America, according to a study by the Natural Resources Defense Council.

Food is considered organic waste. As part of OneNYC, an environmental vision for New York City’s future first created under Mayor Bloomberg and now updated by Mayor de Blasio, the city has pledged to reduce its organic waste output sent to landfills by 90 percent by 2030 to reduce its environmental impact. Some food may still be sent to incinerators

Los Angeles, Austin, San Francisco and Minneapolis also have zero waste plans to minimize the environmental impact of trash. Mayor de Blasio’s plan has eight initiatives—most of which deal with food waste. The initiatives involve food waste in homes, businesses and schools.

Aliza Chasan

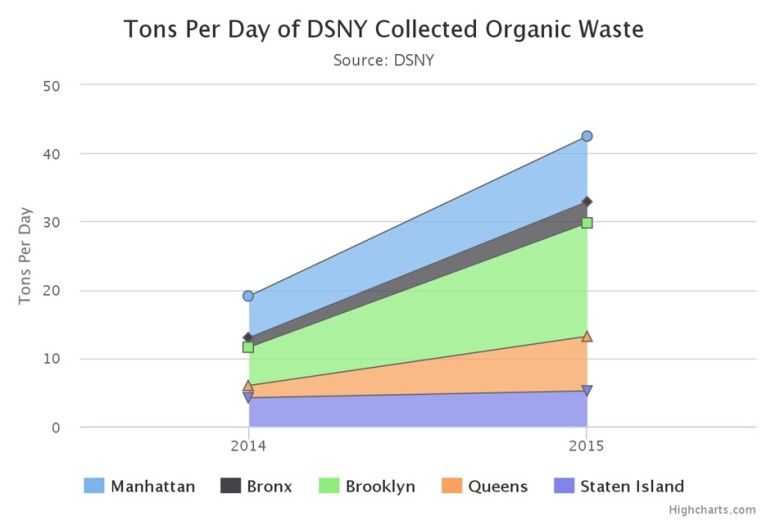

The Sanitation Department collects about 10,500 tons of garbage a day. About a third of this is food waste. The commercial industry, which has its waste handled by about 200 private haulers, generates an additional 5.5 million tons of waste every year, according to a 2015 Transform Don’t Trash NYC study. About 35 percent of commercial waste is organic.

There are ways to cut down on organic waste at home, in offices and at grocery stores including portion control and ignoring sell-by-dates on food, says sustainability expert Jacquelyn Ottman.

There is no national regulation to date-label foods. Nine states don’t even have food dating legislation.

But concerns over food safety mean that most food is thrown out once it has “expired.” There is a right way to determine food safety, says Ottman, who founded a green marketing consulting group.

“It’s usually just a smell test,” she says.

If it smells bad, add it to a compost bin, Ottman says. As part of OneNYC, about 137,000 households, along with 150 high-rise apartment buildings representing about 16,000 households citywide, now have curbside organic waste pickup designated for composting.

“It’s the size of a nice sized city,” says Belinda Mager, a spokeswoman for the Sanitation Department. “It’s a small portion of New York City, but anywhere else that’s a lot of people.”

Freeganism in New York City from Aliza Chasan on Vimeo.

The Sanitation Department plans to add 53,000 low-rise households and 52 high-rise buildings to the composting service this year. Organics collection is scheduled to serve all city residents by 2018.

The organics composting is also in 722 city schools, 28 charter schools and 69 private schools, according to the Sanitation Department.

The Sanitation Department also issued new rules in August that will require 350 hotel restaurants, sports arenas and food wholesalers to separate their food waste from other trash and either compost, reuse, donate or sell it. The mandate will eventually apply to all city restaurants.

Residential compost from the city can go to one of seven taxpayer-funded sites in the city, to a location in upstate New York, to a Connecticut facility or to one of 225 official community-composting sites in the five boroughs.

One of these facilities, the Gowanus Canal Conservancy in Brooklyn, receives about 6,000 to 7,000 pounds of food waste to compost each month. They used to get 10,000 each month from organics collections at city Green markets, but some of what the facility used to get is now being collected by the Sanitation Department.

Natasia Sidarta, a Conservancy program manager, sees less garbage each month now, but she says she is hopeful that the brown organics bins will lead to more composting.

“People who compost now are already aware of the environmental benefits that it has, but we need to trap those people who don’t have that mindset already,” Sidarta says.

It’s a step in the right direction, Kalish says. Ideally, food would be salvaged instead of being tossed out.

“We don’t want to be able to dumpster dive. In a perfect world, there’d be a system where there isn’t any waste from which to dumpster dive,” Kalish says.

City Limits’ coverage of food policy

is generously supported by

the Laurie M. Tisch Illumination Fund.

* * * *

2 thoughts on “NYC Freegans Fight Food Waste One Dumpster-Dive at a Time”

Pingback: The Pigs’ Food for Thought – caroistaa

Hello my name is Yuby Hernandez, and I am a documentary filmmaker at SVA, attaining my MFA. My thesis is about people who salvage items from the trash, and I have currently been working with Anna Sacks “The Trash Walker.”

I would however, love to expand my film to include people who salvage food not just materials and so I was hoping that I could speak to the Aliza Chasan, about connecting with the freegans. Please let me know when we could set up a call