City Hall

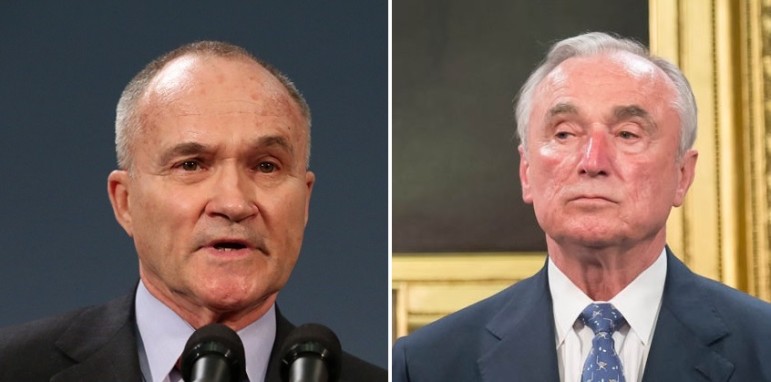

Former Police Commissioner Raymond Kelly (left) and his successor William Bratton disagree with each other. Police reform advocates largely disagree with both of them.

The pretty public spat between NYPD commissioner Bill Bratton and Ray Kelly, the man he replaced, isn’t sitting right with me. It’s not only because Kelly’s pot and Bratton’s kettle offer a dogfight where I have no dog, but because the media and the NYPD have cocooned themselves in a story about a showdown of personalities while a national police brutality epidemic rages on. But let’s face facts, New York reporters can’t be expected to not squeeze every drop out of a juicy testosterone-filled soap opera, so let’s break it down a bit, shall we?

First, let’s briefly touch on how normal crime stat-fudging already is. Has the current Bratton regime played the game of downgrading crimes? Probably. The Los Angeles Times reported that the LAPD did this for many of the years Bratton was the police chief there. But then again this also happened at Kelly’s NYPD, as famed whistleblower cop Adrian Schoolcraft pointed out. From 1PP to your local precinct, crime stat fudging is not so much a political scandal as it is business as usual. Ever since COMPSTAT created a top-down accountability system that pressured police officials to drive crime down there’s always been an incentive to lean away from serious crime, by hook or by crook.

It gets all that much more political in the chair of the commissioner. Bratton, who was essentially brought in by Mayor Bill de Blasio to deflect from his predictable conservative critics (who’ve criticized him anyway), has multiple motivations for painting a rosy crime picture: to protect de Blasio and, more importantly, to protect his own reputation. This has little to do with Kelly selling a book. Bratton, who’s sold his own books, was on cable television during the Kelly years armchair-quarterbacking about Kelly’s methods. Their rivalry is well documented, but ultimately trivial to the real issues with policing.

While Bratton and Kelly envelop themselves heavyweight war of words, with the media playing fight promoters, the source of distrust of the police in communities of color—again, a national theme right now—isn’t because a crime stat might be off by a percentage point or two. Last year Bratton testified in front of the City Council that use-of-force incidents in the department were at all-time lows—claims that were disputed by a Council analyst subsequently fired. Then, over a year later, the NYPD rolled out new use-of-force reporting guidelines, basically admitting that their previous beancounting on police brutality wasn’t serious.

A police commissioner presenting less than accurate use-of-force numbers to elected officials, amid nation-wide police brutality protests, casts at least a shadow of doubt on all the other NYPD numbers: stops, frisks, crimes, shootings, etc.

Here’s some other data reform-minded New Yorkers might want take a closer look at: The mayor and the commissioner insist that stop and frisks are down dramatically. It’s really at the heart of what they say are fulfilled reform promises. They’re also likely at the heart of Kelly’s allegations; he, of course, insisted that any let up on stop and frisks would invite crime and shooting increases. His own motivation (and those of de Blasio’s conservative critics) is to cling to that odious and fictitious myth that stop and frisk kept the city safe.

Again here I take no side. Bratton, whose 90’s stint ushered in the era of Broken Windows policing and expansive stop and frisks—both racist methods in the minds of many—and Kelly, who continued that approach, can argue until they’re red in the face. Both deny any racism in their approaches, with Bratton at times taking a slightly more diplomatic approach than the hard-charging ex-Marine Kelly. Both also deny a well-known quota system that fuels enforcement. Kelly’s erasure of emails that may have acknowledged this illegal quota practice is a brewing scandal in of itself.

But are stop and frisks down as low as City Hall insists they are? Who knows. Stop and frisk data has always been self-reported by cops, not an independent body, which should already raise flags. And with the changing of political winds, from one administration obsessing over random street stops to another seeking a more balanced buffet of police interactions that also includes dedicated quality-of-life enforcement, can come a mandate for less reported stop and frisks. But does that reflect reality? You’d have to trust the cops, I guess—the same cops who overwhelmingly re-elected Pat Lynch, who said the videotaped chokehold of Eric Garner wasn’t a chokehold, to head their union.

My suspicions, however, are that such incredible drops in stop and frisk (from the Kelly era highs of almost 700,000 to this year’s tens of thousands) couldn’t possibly produce almost identical racial disparities. That’d mean police reduced stops in almost the same ratios as they were making them. That has to be some sort of statistical improbability. That merits more scrutiny, in fact. The same numbers-oriented mentality that could push crime stat manipulation could easily translate to enforcement data manipulation.

With this department, quite distinguished from other city agencies for its lack of transparency, it wouldn’t be surprising.