NYCDOE

With 21 district elementary schools (four of which serve grades K-8) and 11 district middle schools, District 3 serves students who reflect the diversity of the city, but its schools are heavily racially and economically segregated, some parents say.

The decision last week by the Department of Education to drop a controversial rezoning effort for District 3 on the Upper West Side has opened a door for longer-lasting alternatives, say parents and advocates.

They have submitted their own rezoning plan to the local community education council in the hopes of repeating the success of cities around the United States.

Based on a method first used in Cambridge, Mass., the plan uses an approach known as “controlled choice,” which combines family preferences with controls to promote equity of access to district schools. Effectively, the method uses both individual student’s ranking of his or her desired school placement along with a computer-generated algorithm that weighs family income, proximity to the desired school, and the percentage of English language learners and children with special needs within the school in deciding where each child should go.

With 21 district elementary schools (four of which serve grades K-8) and 11 district middle schools, District 3 serves students who reflect the diversity of the city, but its schools are heavily racially and economically segregated, according to the District 3 Equity in Education Task Force, which has submitted the controlled-choice rezoning plan.

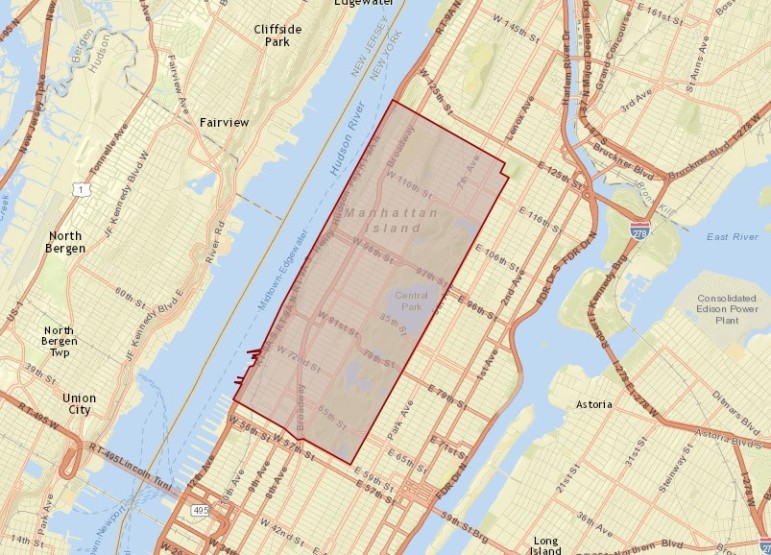

While across the district, which runs from 58th Street to 122nd Street and includes the Upper West Side, Morningside Heights, and Manhattan Valley, 61 percent of elementary school students qualify for free lunch, the assignment of children within that group is heavily concentrated among a group of schools in the district, say task force members.

Using data from the NYC DOE’s 2012-2013 school year, the task force notes that while some of the elementary schools have less than 15 percent of their students qualifying for a free lunch, at least six elementary schools have a student population in which 90 percent or more of the students qualify for a free lunch. In one school, all the children qualify for a free lunch.

Likewise, while District 3’s district-wide proportion of English language learners is 8.8 percent, according to data collected by the NYC DOE in 2012-2013, ELL students comprise 18 percent or more of the population at some schools, but as little as 3 percent at others. In five of the district’s schools, more than 24 percent of the students have IEPs, individualized education plans, meaning they are supposed to receive special-education services, according to the 2012-2013 DOE data.

The disparities extend to the racial concentration of students, according to the report: In a district where more than 66 percent of students are Black or Latino, some schools have between 95 and 99 percent Black or Latino students, while others have less than 30 percent, say the report’s authors.

“Increasingly, more and more community members, elected officials, teachers, parents across the board are talking about segregation in a the way I’ve never heard in 15 years that I’ve worked in this community,” says Ujju Aggarwal, a community activist and member of the District 3 Equity in Education Task Force. “There is an increasing number of people who are saying that something needs to be changed.”

The task force’s controlled-choice plan is based on the model created by Harvard education school professor Charles Willie and education planner Michael Alves. The two men in 1981 created a model of controlled choice in Cambridge, Mass., which focused on a method in which every school enrolled students at a rate that matched the racial demographics of the entire city. The plan was successful, and helped Cambridge avoid the violent turmoil that roiled Boston in the late 1970s, after a federal judge imposed school busing as a way to reassign public school children in Boston’s heavily racially segregated school district.

The success of the Cambridge plan led to its implementation in some form in nearly 30 school districts around the country, from Montclair, N.J., in 1986 to Hartford, Conn., and Milwaukee, W.I., in 1991 to Fayette County, Tenn. in 2014.

For months, parents and community members in District 3 have fought bitterly over a controversial DOE rezoning plan to ease overcrowding at PS 199—a mostly white, mostly wealthy elementary school located at West 70th Street and Amsterdam Avenue—and assign new students to the under-capacity PS 191 at 61st Street and 10th Avenue, a school with much lower state test scores and a “persistently dangerous” designation.

At one particularly contentious Community Education Council hearing in late October, some angry parents tried to shout down the principal of PS 191, Lauren Keville, when she stood up to talk about improvements in the school. Other parents lined up to warn that they would leave the district, where they had bought apartments, if they were rezoned for PS 191.

While Mayor Bill de Blasio has said that the city has to “respect” families’ decisions to buy property based on proximity to good schools, the DOE is slowly moving toward allowing some schools to test pilot admissions policies that factor in students’ socioeconomic status when admitting new students.

Under one previous DOE proposed rezoning plan for District 3, some apartment buildings now zoned for PS 199 would have been rezoned for PS 191. While students already enrolled in the elementary school would have been allowed to stay, new students would have been redirected elsewhere. That proposed block-by-block re-designation drew the greatest number of critics to the CECD3 meetings, where homeowners lined up to decry the DOE’s efforts to cut their families out of the school zone to which they had planned to send their children.

Last Tuesday, Nov. 17, the DOE announced it had postponed its rezoning proposal for District 3, saying that it needed more time to work with the community members to find a long-term solution to the issue of overcrowding. Three days later, the DOE also announced that it was piloting new admissions policies at seven elementary schools around the city to promote diversity. As part of those admissions policies, the schools will give priority to students who qualify for a free lunch, to English Language Learners or students in the welfare system. The changes will go into effect for Kindergarten admissions for the 2016-2017 school year.

Elsewhere around the city, other school districts have applied for and received state approval to develop and pilot their own admissions policies. This past year, the New York State Education Department awarded eight federal grants of $1.25 million each to eight schools around the city to increase diversity and implement admissions policies that account for families’ proximity to the schools, as well as family income and children’s needs. The grants, known as the Socioeconomic Integration Pilot Program (SIPP), also call for the creation of a family resource center in each district where parents can easily access information about all the schools and receive assistance in weighing the merits of each one.

The schools participating in the SIPP include one elementary school (PS 15 Roberto Clemente School in District 1), four middle schools—MS 113 the Ronald Edmonds Learning Center in District 13 in Brooklyn, Frederick Douglass Academy II in Manhattan, Bronx Writing Academy and IS 117 Joseph H. Wade in the Bronx—as well as three high schools, all in Brooklyn: the George Westinghouse High School in Downtown Brooklyn, Boys and Girls High School in Bedford-Stuyvesant and the High School for Global Citizenship off Eastern Parkway near the Brooklyn museum.

To date, the schools have received initial funds to each create a community-wide planning process to shape the new admissions policies. The planning and implementation process is expected to take 12 to 30 months. All eight schools are Title 1 schools, meaning that more than 60 percent of the students qualify for a free lunch.

David Goldsmith, president of Community Education Council District 13 in Brooklyn, said his district was at the start of the process of developing a pilot admission policy. “What we are trying to do here is organize a community engagement across the district to really look into this difficult issue of ‘what do we mean by diversity?’ How can we turn this into a reality and something that everyone thinks is fair and based on values that there’s consensus on.”

Continues Goldsmith: “The main goal is academic excellence. What we are trying to do here is make great schools.”

While District 3 in Manhattan does not have a school that is on the SIPPs grant list, the District 3 Equity in Education Task Force has submitted its “controlled choice” plan to the CECD3 for consideration and discussion. If a form of controlled choice were to be implemented, the group acknowledges the importance of grandfathering in students enrolled in schools where they want to stay and allowing siblings to also attend those schools. The most important part of the process is transparency, says Aggarwal, in the creation of any new admission policy.

“It’s not just a problem of overcrowding and segregation and inequality that no one can ignore,” she says. “We are trying to promote district-wide solutions to what we see as a systematic problem.”

One thought on “Some in Manhattan Want ‘Controlled Choice’ to Diversify Schools”

Pingback: Building Justice: Segregation in NYC Schools is No Accident | City Limits