Crocodilesareforwimps

A side effect of the news out of the U.S.-Iran talks in Lausanne is that people are once again talking about The Bomb. Since at least the fall of the Soviet Union, fear of The Bomb has all but evaporated. But there are abundant reminders around New York—namely those dingy, dented Fallout Shelter signs that grace many a brick wall in the city—of when people thought a lot about nuclear war and how to prepare for its arrival.

And for those of us who grew up at the end of the Cold War (my hometown tested its air raid siren every Friday at noon until at least the late eighties) it’s instructive to read how New York assessed its risk when the fear of nuclear annihilation was pretty intense.

In 1959, a special task force presented a report to Gov. Nelson Rockefeller entitled “Protection from Radioactive Fallout” that offers an astounding mixture of doomsday pessimism and can-do survivalism.

NYS

From “Survival in a Nuclear Attack,” a 1960 New York State report.

“The threat of fallout from nuclear weapons launched by an enemy poses perhaps a greater hazard to the lives of our citizens than any other which our society may be called upon to face,” the report begins. “We do not believe that nuclear war is inevitable,” the authors continue—clearly implying that some folks did think it was inevitable—but “if a test of military strength … does become necessary, we believe that or people and out democratic society can be successfully defended.”

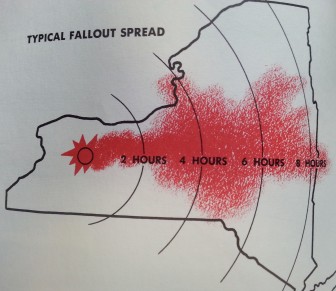

Not that it’d be easy: The report described a simulated attack involving 40 nuclear weapons dropped on New England, New York and New Jersey—as well as other hits on Ohio and Pennsylvania that sent radiation into the jet stream—which led to 5 million deaths in New York, 77 percent of them not from the initial blast but from fallout. (For those who didn’t grow up having nightmares about “The Day After,” fallout is the radioactive particles that would rain down in the hours, days, weeks and months after a nuclear blast.)

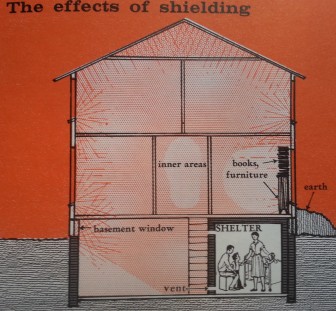

The good news, Rockefeller’s task force reported, was that fallout dissipated rather quickly: Between the first hour after a nuclear boom-boom and the seventh hour, radiation levels would fall 90 percent. Even better: You could improve your chances for surviving World War III without busting your family budget! “On a do-it-yourself basis, the cost of fallout protection for existing homes with basements could be as low as $150. And for less than $500 added to the normal cost of construction, virtually complete protection from the most foreseeable radiation from fallout would be provided in a new house with a basement,” the 1959 task force reported. “With planning, too, the protected area can serve a dual and daily use in family activities.” (There was even a property-tax exemption on fallout shelters in New York. And they could be kind of mod-looking.)

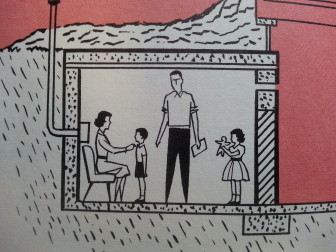

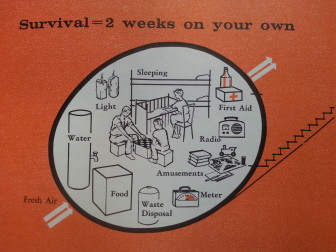

One thing that wouldn’t be welcome after The Bomb would be a lack of preparedness. “Every individual who survives the initial blast is asked to be prepared to exist for a minimum of two weeks following an attack without outside help.” The next year, a follow-up report, “Survival in a Nuclear Attack,” even provided a sample menu of what kind of fallout-shelter fare Mom might serve up. The lineup of peaches, spinach, peas, baked beans with pork, cocoa (instant) and hard candies doesn’t sound like a bad way to get through the first few days of post-apocalyptic life—especially if, as one drawing suggests, you had some “amusements” on hand to help pass the time.

What’s interesting about the illustrations in both New York State guides is that virtually all the fallout shelters depicted are in the sub-grade areas of detached, suburban houses—not in the basements of apartment buildings or schools where New York City residents would have scampered when the siren sounded. Maybe that was a typical anti-urban bias at play. Or perhaps it was an honest recognition that, as civil-defense dissident Mary Sharmat wrote, “New York City would become a desert in the event of nuclear war.”

The assumption always was that while the Soviets’ first priority would have been wiping out U.S. military installations, their enemy’s largest population center wouldn’t have been far down the target list, meaning the city wouldn’t have had a chance to worry about fallout. That fact adds a certain poignancy to the absurdity of this newsreel report about a citywide air-raid drill:

Today, as you’d expect, New York’s civil preparedness outreach de-emphasizes the potential for a nuclear attack. The Office of Emergency Management lists “radiation exposure” on its roster of hazards but its brief treatment doesn’t specify whether it’s an Indian Point meltdown, dirty-bomb or ICBM we should be worried about.

The Department of Health and Mental Hygiene, however, distinguishes between “radiological” incidents (like dirty bombs, which spread radiation but don’t involve an actual nuclear explosion) and “nuclear” incidents (actual fission or fusion devices). DOHMH offers pretty extensive FAQs on both types of threats, the latter of which contains a line that suggests just how far we’ve come since the days of duck-and-cover:

“A nuclear explosion can be very stressful, especially if it is large scale event. It can disrupt your everyday life and make you and those around you feel less safe. You may experience fear and uncertainty.”

UrbaNerd explores the trivia, history, science and silliness that help make New York City the greatest place on Earth.