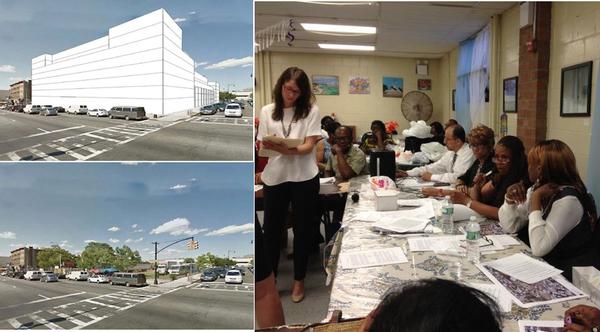

Photo by: Department of City Planning, Tobias Salinger

The plan (top left) and current look (bottom left) of the Rheingold site. Jennifer Dickson, standing, a lawyer representing Read Property, takes notes as Bushwick Community Board 4 District Manager Nadine Whitted expresses concerns about the Rheingold development.

Osvaldo Valdez didn’t know that his uniform business on Bushwick Avenue lies on the proposed future site of mid-rise apartments. But he said the recent sight of a person toting blueprints gave him reason for pause.

“I saw someone walking around with the plan in his hands and I said ‘Oh my goodness,’” says Valdez. He sells work clothes for mechanics, construction workers and custodians out of a mobile home in one of two dusty industrial lots slated for residential use by a plan being considered under the city’s Uniform Land Use Review Procedure at Bushwick’s Community Board 4.

Read Property Group’s plan to build 977 rental housing units on the remaining land of the former site of the Rheingold brewery has encountered concerns about rising rents and dwindling park space in Bushwick. As representatives for the company look to address reservations along the way to approval by the City Council, local officials and advocates are making a push to solicit more community input.

“The developers should hear these questions,” said Community Board 4 District Manager Nadine Whitted at a hearing on the zoning changes on June 19. “Please understand that this project is very important to this board. We’re trying to shape the next 10, 15, 20 years.”

Rezoning required

Whitted and other members of the board voted to hold another meeting on the Rheingold application at a date that has yet to be announced. The board has until Aug. 12 to submit a recommendation to the borough president, according to the Department of City Planning. Under the ULURP process, the proposal then goes to the City Planning Commission, followed by the City Council, and then the mayor. The community board and borough president opinions are advisory, but sometimes carry weight with the planning commission and Council.

The proposed construction, which would be completed by 2016, involves erecting 10 buildings up to eight stories high with ground floor retail space, carving out two new blocks in the neighborhood and either adding capacity at nearby P.S. 120 or building a supplemental school facility. The project requires ULURP approval because the two lots currently zoned for industrial use would be rezoned as residential and a warehouse that is not a part of the development plan would be rezoned for lighter industrial uses. The lawyer representing Read Property at the hearing, Jennifer Dickson of Herrick, Feinstein LLP, says the developers’ proposal utilizes unused space.

“They are more or less completely vacant,” she said in a telephone interview about the two industrial lots. “Our client has tried to provide something that is contextual, that fits into its surroundings.”

Read Property first submitted its proposal to City Planning in December 2006, records show. A 402-page draft environmental impact statement prepared by Philip Habib & Associates contains extensive studies on everything from brewery-era hazardous substances to traffic patterns and shadows that would be created by the buildings. The plan calls for 24 percent of the units, or about 242 of them, to be affordable.

Caution about promises

Councilwoman Diana Reyna, whose district includes the proposed development, remembers the initial phase of development on the Rheingold site as her first foray into land use on the City Council. That process yielded approximately 300 units of apartments, multi-family homes and condominiums aimed at moderate to lower-income residents; it opened in 2003. She says she wants to ensure that Read and the city live up to whatever agreements are made during the land use process.

“It’s important that we understand that what’s on paper doesn’t always play out,” she says, referring to lessons she learned during both the first phase of Rheingold and the 2006 rezoning of the Williamsburg and Greenpoint waterfront.

Reyna expresses concern about how the project will affect space for playgrounds and parks. The environmental study notes the Rheingold development will have a “significant adverse impact” on open spaces in a neighborhood with a low concentration of parks. Though no parks would be “displaced” by the project, the influx of new residents and retail workers would reduce the ratio of available open spaces to people. The study cites the developer’s proposal to add public recreation space between two of the buildings as an effort to address that criticism and Dickson asked community residents at the board meeting for input on what features would attract visitors to the park.

“We want to continue to take feedback of what should be there and what shouldn’t be there,” the developer’s representative told board members after presenting the plan.

But Reyna says she would like to see more open space, something she said developers have been “receptive” to. In an interview at her Williamsburg district office, she pointed on a large map of the project to a triangle on Bushwick Avenue and Beaver Street that had been slated for park use in the prior phase of the Rheingold development.

“We’re still waiting for that benefit, and, in the mean time, the city is moving forward on the next rezoning,” says Reyna.

Defining “affordability”

Reyna has coordinated ongoing negotiations with Read and its principal, Robert Wolf, alongside Churches United for Fair Housing, a North Brooklyn coalition of 40 churches devoted to helping longtime residents stay put in their communities. Rob Solano, the group’s executive director, described Read representatives as “reasonable” after they met with Churches United leadership and agreed to make a public presentation with a question and answer session for area residents later this month or in early August.

“I think these developers did their research,” said Solano in a phone interview. “They heard about who we are.”

Yet the issue of affordability might prove the thorniest of all for the developers in a neighborhood both bracing for and already experiencing gentrification.

Census data cited in the environmental impact study shows that the area within a quarter-mile radius of the development has a median household income of $28,089, far below the Brooklyn average of $45,487. Yet the average monthly rent price for a one-bedroom apartment in Bushwick rose by almost 63 percent between 2006 and 2010, from about $800 to almost $1,300.

The low-priced units at Rheingold would target households of up to 60 percent of the city’s adjusted median income (AMI), roughly $36,000 to $53,000. Dickson said at the board meeting that a one bedroom would have a rent of up to $1,067 a month and apartments for seniors would have lower rents.

Reyna says she will seek more affordable housing in the proposal. She praised Read’s willingness to incorporate affordable units as “commendable,” but she also noted that “99 percent” of the constituents who request aide from her office are looking for help with housing needs.

Dickson said the developers would consider increasing the amount of affordable housing.

“Our client does expect that he will pursue some subsidy,” she said. “Whether they do something additional will depend on what kind of subsidy they can get.”

Secondary effects are a concern

Solano said leaders at Churches United both asked Read to raise the number of affordable units and said they would help them find funding to do so.

“Let’s work together and find a program to get it there,” said Solano. “They’re open to figuring out how to get more affordable housing and how to get lower AMI.”

Read already gained one benefit through the city’s inclusionary housing program. Since the company pledged 24 percent of the units to be affordable throughout the life of the development, they will be allowed to build even higher buildings that the new zoning they seek would normally permit.

But the environmental impact statement reports no “significant” direct or indirect displacement of residents due to the project. “The area is already experiencing an ongoing trend toward more costly housing and a higher income population,” reads the report’s assessment of the Bushwick real estate market. “The proposed action would represent a continuation of this trend.”

Reyna disputes that conclusion. The speculation of new development is what pushes rents up and displaces people from the neighborhood, she says. “And that’s not a part of the report.”