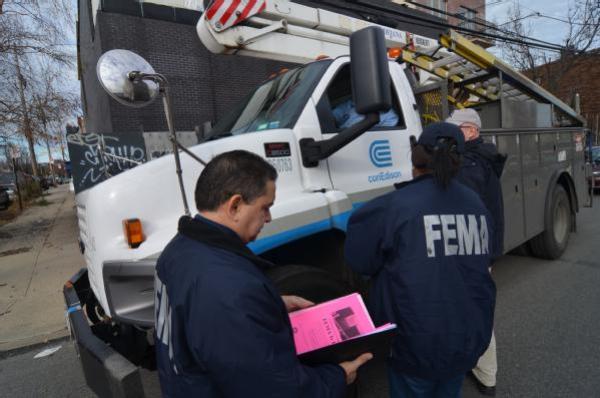

Photo by: FEMA

FEMA workers in Red Hook on December 11.

It wasn’t long before some big numbers began getting thrown around in the wake of Superstorm Sandy. The city approved $500 million in emergency capital funding. Regional leaders asked for $80 billion in federal help.

For renters, homeowners and businesspeople affected by the storm, the amounts they need—and the help they are getting—are far smaller but just as significant. Here’s a quick look at how the aid system is working so far.

Q: How does FEMA approach aid?

A: “FEMA is assigned to a state,” FEMA Spokesperson Ed Conley says. “At that point, there are two options—either FEMA uses its own core of engineers to hire and perform the necessary repairs, or if the state in question has the capabilities at the time of the event, FEMA will reimburse that state’s efforts.”

Q: What is does FEMA consider to be its jurisdiction?

A: FEMA aid focuses on housing—paying for people’s temporary housing needs, and assisting with repairs and replacement of damaged structures. FEMA’s mission is to create a “safe place to live” for every American, Conley reports, and deploys two methods towards securing that end. FEMA puts money directly into the hands of homeowners, based on certain eligibility criteria: the damages must be sustained to a primary residence, the insurance must have refused coverage, it must be located in an impacted area, and it must represent unsafe living conditions. FEMA has already approved $700 million of aid directly to homeowners in the wake of Hurricane Sandy, either as a grant for repairs or assistance paying for emergency housing.

Q: What if someone isn’t eligible? What aid can they seek?

A: In the instance that someone fails to meet the eligibility criteria, FEMA has a second method for assisting residents back into their homes: they will reimburse the Mayor’s efforts. The city’s response to Sandy has been to send subcontractors to homes to restore heat, hot, water and electricity. Originally, these contractors were working down a list, but recently the Mayor’s office announced the Rapid Repairs program, in which a team of contractors would be sent block by block to do restorations, rather than by individual request. Individuals need to register with FEMA to be eligible for Rapid Repairs. Separately, businesses can get aid through the federal Small Business Administration or the city’s Small Business Solutions.

Q: Who does the repairs?

A: The city has also received a grant of over $27 million in Disaster Emergency Funds to be put towards hiring unemployed individuals to do Sandy clean up, Governor Cuomo’s office reports. Some of that funding goes to contractors who hire their own subcontractors. These firms are encouraged in their contract with NYCHA to “make every reasonable effort to hire NYCHA residents,” Spokesperson Sheila Stainback says.

Q: What other kinds of assistance are available after the storm?

A: Nongovernmental organizations have been active, from the Red Cross to Occupy Sandy. The Brooklyn Community Foundation (which funds Brooklyn Bureau), Brooklyn Chamber of Commerce and Brooklyn Borough President’s office launched a Brooklyn Recovery Fund that’s raised more than $1.5 million and distributed at least $450,000 so far. Residents of a Florida retirement community’s “Brooklyn Club” sent money. The children of a Hawaiian day school collected 100,000 pennies. Barclays Center and the Brooklyn Nets each pledged $100,000.

Q: How is the Relief Fund’s money distributed?

A: The Fund offers grants of $5-10 thousand dollars to specific non-profits or small businesses to help with anything from replacing computers to providing food for their communities. They goal is to help non-profits help the communities they already serve. So far, BCF has funded 26 neighborhood organizations with a total of $250,000. On November 16, BCF issued a request for proposals for a different kind of aid. They asked communities to form coalitions from their many non-profits. These coalitions would be eligible for much larger grants, and the aim of creating them would be twofold: BCF would be investing in a community-based, community-run relief effort, but they would also be investing in community strength. Two coalitions have since been formed—one in Coney Island and one in Red Hook, both neighborhoods with a strong not-for-profit presence, though this will be the first time all are gathered under one heading. Each neighborhood has been awarded $100,000 towards recovery efforts.

Q: What is the difference between the operations of NGOs and governmental aid?

A: Laura Gottesdiener of Occupy Sandy, an offshoot of Occupy Wall Street, explains: “Our principle from day one has been to assist communities in tapping into the power that already resides within them, even after a disaster.” Gottesdiener says that the Occupy movement focuses on redistributing community resources, going door to door and helping people get out, organizing community meetings, and helping a community provide aid to itself, rather than “just throwing a bunch of resources at them.” The point of this is to provide long-term reconstructive help, directed by the communities themselves. “The city doesn’t ask people what they need. For example, the first money that came in went to paying the police for their overtime. We are using Sandy as a way of investing in communities. People don’t realize how much organizing experience they already have.”

Q: Are the Red Cross’s efforts more like FEMA or more like NGOs?

A: The majority of the Red Cross’s funding comes from donations, from individuals are corporations. Right now, their Sandy Relief Fund has $202 million in donations and pledges, Spokesperson Melanie Pipkin reports. The Red Cross follows a disaster plan to find out where need is located which includes being in touch with local officials and following social media sites. Their operations include providing shelters, meals, and relief items, but they work large scale. When people want to donate smaller scale items, like cans of food, or coats, the Red Cross will partner with smaller organizations such as Occupy Sandy to distribute these donations.

Q: What lessons can we learn from the response so far?

A: Brooklyn Community Foundation president Marilyn Gelber thinks that in light of the unique setting New York provides to disaster relief efforts, “FEMA must seriously reevaluate how to provide relief in an urban situation like New York City.” She questions FEMA’s decision to allow the city control over Rapid Repairs, arguing that city agencies have little knowledge of who needs what. She cites NYCHA as an example of particularly poor response. “There is no community organization,” she says. “Sandy and the poor response to public housing have provided a lesion in the need for restructuring. Its residents are not being well served.”