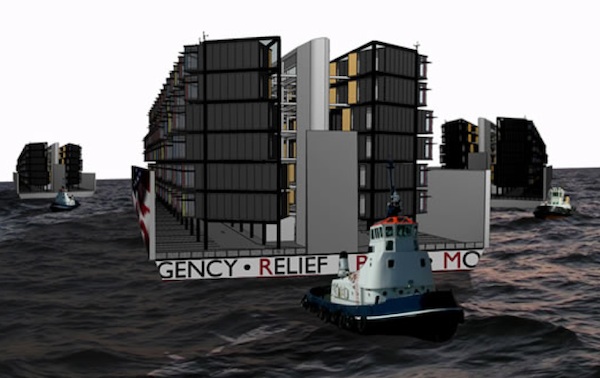

Photo by: OEM

One winning design, by Matthew Francke and Katya Hristova, called for bringing in modular housing by barge, and anchoring the structures side-by-side to create a temporary neighborhood.

What if the most densely residential city in the country loses hundreds of thousands of homes in a few hours? What if millions are left with nowhere to live, to work, or to go to school? What if subways flood, streets close, and whole neighborhoods are submerged by up to 23 feet of ocean water and battered by 130 mile-per-hour winds? What if New Yorkers need a place to live during years of reconstruction?

Such was the set-up to a design competition sponsored by New York’s Office of Emergency Management in 2008 called “What If NYC?” that attracted entrants from around the world to share proposals for how the city could house thousands of people quickly and close to where they lived before a disaster.

On Sunday Mayor Bloomberg estimated that 30,000 to 40,000 people might need to relocate at least temporarily. That’s almost identical to the one the city gave to designers in 2008, when they were asked to envision a situation in which 38,000 households “will seek housing for some length of time, from one month to up to five years.”

[Update, Monday, 3 p.m.: In a conference call with reporters, federal housing secretary (and former New York City housing commissioner) Shaun Donovan declined to estimate how many residents might be uprooted from their homes during the recovery process, but said that so far relatively few had been relocated.]

In a city with a tight housing market and 40,000 people living in homeless shelters even before Sandy hit, that’s a huge challenge. The fact that most of the real-life displaced will be public housing residents only increases the stakes.

After the levees failed in New Orleans in 2005, much of the population left the city and even the state for weeks or months. Some never returned. The city came back smaller, richer and whiter. And, in what’s still a controversial move, several public housing complexes were torn down and replaced with mixed-income housing.

Forty-thousand people in a city of 8 million isn’t Katrina-grade displacement. But with public housing already under tremendous pressure in New York—home to the nation’s first and largest public housing system—how and where those tenants are temporarily housed will have political implications. As the city’s “What If?” website wrote:

The temporary housing that is the focal point of this Competition is called provisional in the sense that it is intended only as an interim step until a permanent solution is achieved. When residents return to live in Provisional Housing in their previous surroundings, they can be active participants in the City’s long-established planning process that will determine the permanent reconstruction of their communities.

The 10 winning designs in 2008 reflected a range of visions for post-disaster New York, each combining the plainly practical with the boldly futuristic. In a flooded city, one winner suggested floating modular housing on barges. Another called for placing the new housing on scaffolds above streets to minimize the impact on scarce, dry land.

Oddly enough, the imaginary neighborhood in which the disaster plays out, Prospect Shore, has a poverty rate of 28 percent—identical to what prevails in the community district that includes hard-hit Coney Island.

The jury report from the competition says that after the 10 winners present more detailed plans (which they eventually did), “One or more of these more-developed proposals may be selected by OEM to move on to the stage where a prototype is developed.”

OEM did not return by press time a question about whether any further development occurred.