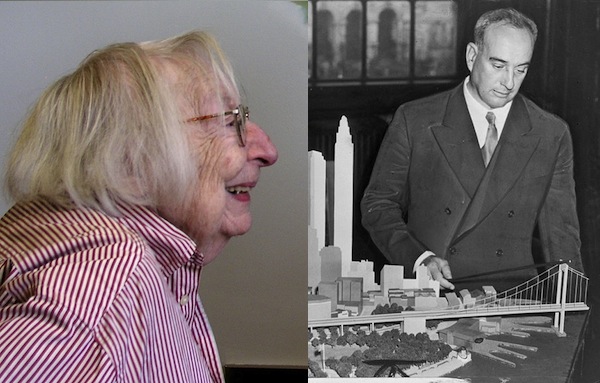

Photo by: Classical Geographer/Library of Congress

Jacobs and Moses: Enemies who created the modern city

“The Battle for Gotham: New York in the Shadow of Robert Moses and Jane Jacobs”

by Roberta Brandes Gratz

Nation Books

400 pages

$27.95

What is at first jarring about Roberta Brandes Gratz’s latest book is how much of it is about Roberta Brandes Gratz. Her childhood in the city and the ‘burbs. Her life as a young reporter. Her husband’s metal fabrication business. Her reporting on Westway. Her chats with an old friend. She is as big a character in this story as either of the icons that her subtitle salutes. There is not the slightest effort made at objectivity.

Thank goodness for that. A book that adopted the pretense of detachment, and treated New York as an entity to be observed from a distance rather than lived up close, would not only have been boring, it would have undermined the central idea—and the essential truth—of Gratz’s work: that New York cannot be studied from 15,000 feet because no one lives it from up there, that it can only be understood at the human level.

Thus, this story of Robert Moses’ heyday and fall, Jane Jacobs’ rise and departure and the subsequent decades of contest between their two antithetical notions of the city is told as Gratz saw and lived it. And lives it still. For the contest between those two visions is far from over.

Moses passed away in 1981, more than a decade after Nelson Rockefeller finally drove him from power. Jacobs, who had long ago left the city for Toronto to protect her sons from the Vietnam draft, died in 2006.

The following year three museums in the city undertook a re-examination of Moses—the master builder of roads, clearer of “slums” and maker of parks who had been an urban pariah since Robert Caro’s 1974 biography “The Power Broker.” Caro’s book is enormous and dense with detail about Moses’ 50 years of public life. By comparison, the image that many of Moses’ detractors held of him (your author included) was simplistic, cartoonish. So the exhibits delivered some important nuance.

But the problem with the Moses project of 2007, as Gratz observes, was that it stretched reexamination into rehabilitation. Suddenly Robert Moses was the reason New York had become a modern city, as if there had been no plausible way for the New York of 2010 to be created without, say, the Cross-Bronx Expressway cutting through the heart of the Bronx or Lincoln Center obliterating a West Side neighborhood. “The physical achievements, whether judged good or bad, are undeniably mighty in breadth, scale and obstacles overcome,” Gratz writes of Moses. “But the danger in a revisionist view of history is that it takes on a life of its own.”

Worse still was the timing of this Moses revival, coming at the end of a development boom that was Moses-esque in its scale and deafness to public outcry, from Atlantic Yards to Yankee Stadium to Willets Point. Community plans were pushed aside to meet developers’ demands. Huge public subsidies were proffered and the threat of eminent domain brandished repeatedly. The defense of Moses was easily repurposed as a defense of the city’s new power brokers, whose excesses Gratz details.

The book is hard to categorize. Part biography, part urban history, sometimes manifesto, sometimes love letter to New York. Gratz, a former New York Post reporter who has penned several books on urbanism and has contributed to City Limits in the past, is probably one of the most authoritative interpreters of Jacobs’ legacy.

But while Jacobs is a huge presence in these pages, the book avoids hagiography. These are mostly Gratz’s own ruminations about the city: her recounting of the battle to save SoHo, the process she went through to understand the fullness of Westway’s threat, the decades of punishment she has seen delivered unto manufacturing in New York neighborhoods like Willets Point, the immense value she sees in the small wonders of the Upper West Side. She has much to say, and the book’s structure can sometimes cloud its take-home message, but its fine-grain detail helps it avoid broad-brush ideology that could be a turnoff for the general reader. It’s not that every development or City Hall proposal is a bad idea. There are good developers, and communities sometimes pick bad fights. The only absolute is that not everything labeled “progress” actually is.

Gratz’s timing could not be better. Now the real estate boom is over, but the bruises from the battles of 2002-2007 remain, and there is a feeling that New York needs to figure out a better way to change—a more rational way to implement the PlaNYC vision of a sustainable New York and a more democratic way to incorporate what communities want their city to look like.

When the mayor appointed a charter revision commission last spring with the implicit mandate of re-tightening the term limits he had loosened, there were many calls for the panel to also look at how New York plans its physical future.

The commission refused, blaming the complexity of the issue for its failure to act. As cover stories go, it was a good one, not because of the technical complexity of land-use and zoning, but because of the thorny contradictions that knot the question of how a city should grow.

To see these in action, go to any of the Bloomberg-era bike lanes or high-speed bus paths that have spurred community opposition. Depending on where you sit, it can be easy to dismiss the other side of such disputes. But it’s not so simple. Giving communities a veto over improvements like bike lanes suggests that parochialism has the same standing as the health of the city’s people and the planet. But suggesting that City Hall may, with the stroke of a pen on a map, alter neighborhoods without consulting a soul has a distinctly undemocratic tinge (one that a recent City Council measure seeks to at least reduce by forcing the city to explain why it puts bike lanes where it does). The truth is that when it comes to New York’s physical present and future, good ideas can die for good reasons. Was the death of congestion pricing a defeat for sound environmental policy or a triumph of democracy? Is “all of the above” an option?

These paradoxes are reflected in the fact that both Robert Moses and Jane Jacobs opposed master planning in New York. Moses resisted all efforts to curtail his power, and saw a publicly produced plan as a threat. Jacobs saw master planning as top-down, ill-informed and contrary to the organic, disorganized growth the makes cities special. But in the absence of a plan, do we get egalitarian spontaneity or the false, uneven “freedom” of the free market?

Gratz answers the question: We get both. In New York since Moses’ fall and Jacobs’ departure, and especially since the nadir of the fiscal crisis, the greatest engine of resurgence has been small-scale community efforts to improve a lot here, a block there, all adding up to major movements like the regeneration of the South Bronx. But Atlantic Yards-type projects happen too. And government inevitably plays a role in all of it: Supporting, hopefully, community-based redevelopment; subsidizing, foolishly, massive developments; and abetting the destruction of manufacturing in New York, as Gratz’s most powerful chapters detail.

Could New York get one without the other? Would we get bike lanes if we asked Borough Park where they wanted them? It’d be distinctly counter-Jacobian to make any guarantees—disorder is what defines the city, after all. But a more inclusive process of deciding what to do with New York’s precious land might at least up the odds. While you’ll never get 8 million people to agree even on what day it is, most of the successful development projects in New York have had grassroots buy-in, as Gratz notes, and most of those that people still hold their noses over did not.

The public, writes Gratz, “has come to understand their right and value in being part of the process that leads to change. This is vintage Jane. Public process, on the other hand, was anathema to Moses.” She adds later: “If you accept the centrality of the idea of people being the best engine of change, then what is critical is removing the kind of impediments that thwart the capacity of the people.”

It’s not a terribly specific prescription. But then Gratz is still, as Jacobs always was, suspicious of the arrogance of all-encompassing ideas on planning, or at least the risk of such arrogance. She’s not opposed to all plans, however. Nor was Jacobs. In a 2005 letter to Mayor Bloomberg that Gratz prints in full, Jacobs weighed in on the city’s proposal to rezone the Brooklyn waterfront in a way contrary to what the community had asked for in its own official vision, called a 197-A plan.

“If you follow the proposal before you today, you will maybe enrich a few heedless and ignorant developers, but at the cost of an ugly and intractable mistake. Even the presumed beneficiaries of this misuse of governmental powers, the developers and financiers of luxury towers, may not benefit; misused environments are not good long-term economic bets,” Jacobs wrote. “Come on, do the right thing. The community really does know best.”