Photo by: Patrick Egan

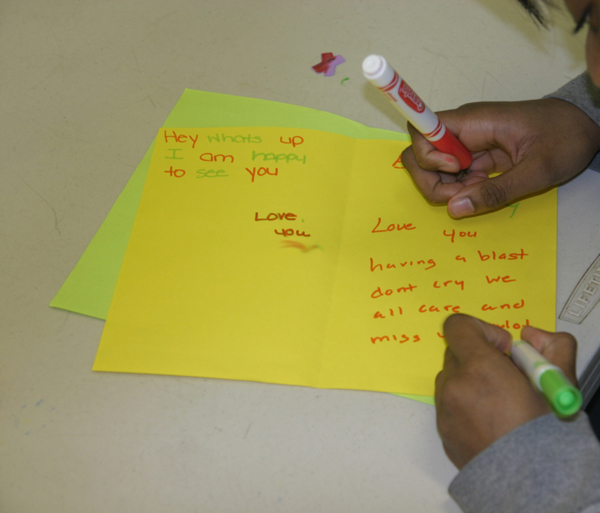

One of the children preparing to visit Albion prison prepares a card for her mother.

On a Friday morning in April, a yellow school bus rumbled over train tracks and onto the parking lot of the Albion Correctional Facility in Albion, N.Y. These were the last few feet of a journey that had started before the previous day’s dawn.

“This is jail,” said Maria, a four-year-old from Manhattan’s Lower East Side, to her chaperon. Maria wore a white taffeta dress embroidered with lavender flowers. Glittery silver shoes further dolled up the outfit. Her curly brown hair fell over the gray hoodie she wore against the chilly upstate air.

The bus came to a stop and its 15 young passengers got off. All had at least one thing in common: Their mothers were incarcerated at this medium-security state prison, the state’s largest for women, located about halfway between Rochester and Buffalo. All but one of the kids on the trip live in the New York City area, nearly 400 miles away from Albion.

Almost three quarters of the 2,422 women in New York state prisons are mothers, according to the Women in Prison Project, a nonprofit effort to advocate for incarcerated females. More than half of those women are from New York City or the surrounding suburbs. That puts the mothers from the city serving at Albion between seven and eight hours away from their kids.

From the bus the children filed into the Visitors Hospitality Center, where all visitors to Albion register before entering the prison. The room was quiet. Fridays are not official visiting days. This was a special event, set up by the Osborne Association, a New York City nonprofit that advocates for incarcerated people and their families.

Four sisters from Queens took the seats closest to the door, as if they knew they’d be first into the prison. Tamara, 18, a freshman at John Jay College, held her sister Sophie, 2, on her lap. Serena, 14, and Dana, 11, sat next to them. (The names of all children mentioned in this article have been changed out of concern for their privacy and safety.) Sophie worked a blue-green pacifier around her mouth. Her sisters’ faces held blank, almost tired looks. They knew they were a few hundred yards from the mother they hadn’t seen since August.

“My stomach started hurting,” Serena said later. “I was anxious. I wanted to see her. And then we had to sit and wait.”

Waiting is something Serena and her counterparts on the bus have much experience with. Inmate mothers often are the only parent in their children’s lives, according to the Women in Prison Project. The vast distance between Albion Correctional Facility and New York City is a huge obstacle by itself. Couple those miles with the circumstances of poverty these families often shoulder, and regular visits are extraordinarily difficult and prohibitively expensive.

Twice a year, through the Osborne Association’s Family Ties program, led by Diana Archer, the nonprofit shuttles up to 25 kids north. It’s too far to drive. With a team of volunteer chaperons, many from St. James Church on Madison Avenue in Manhattan, the children take a short flight to Rochester, and everyone stays in a hotel for the night before visiting the prison the following day. The trip is free for the children—making it a lifeline for families too poor to afford the journey on their own.

“Poverty is at the top of the line of reasons” for why families can’t make it to Albion, said Elizabeth Maldonado, who’s been teaching the parenting class for Osborne for several years. She said that children of incarcerated parents often end up with a grandparent, and that they usually need financial support from social services. “It’s never enough,” Maldonado said of those benefits. “They only do the bare minimum. It just gets [families] to the poverty level. It’s not enough to do extracurricular stuff, like visiting their mother.”

Linda Smith, the grandmother to the four girls, is making it, but not by much. “With shoestrings, we manage,” she said. Smith feeds four growing girls and herself on an administrative assistant’s salary and a little bit of public assistance. The city recently cut the family’s food stamps because Tamara was going to college and not participating in a welfare work program. “The welfare department is disgusting,” said Smith.

The journey to Albion had begun before dawn on the previous day, as children left their homes in New York City for rides to the airport. From a plane they took a bus to the Vineyard Church in Rochester, where they killed time playing UNO, Go Fish and basketball, and crafting cards bearing messages of love and congratulations for their mothers. They played in a pool, went to bed, and got on the bus again to visit their moms in jail.

This story is the first in a three-part series. To read Part 2, click here. For Part 3, click here.