Photo by: David Alm

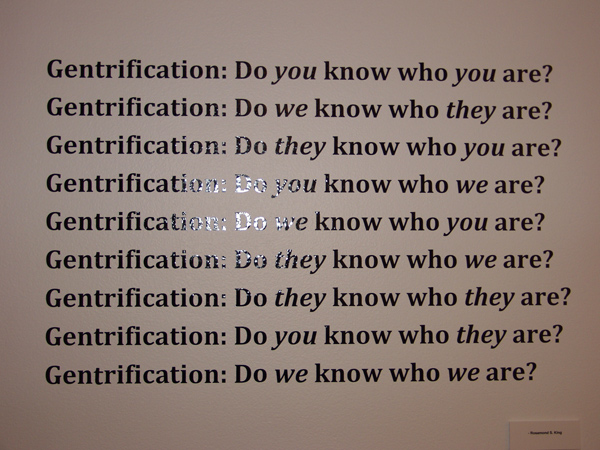

“Untitled,” by Rosamond S. King.

“The Gentrification of Brooklyn: The Pink Elephant Speaks,” at the Museum of Contemporary African Diasporan Arts, 80 Hanson Place, Brooklyn. Open Wed. – Sun, 11 a.m. to 6 p.m., Suggested donation $4, through May 16.

Anyone who’s lived in New York for a while has done it: Walked down a familiar block and remembered the old days – even three or four years ago – when that yoga studio was a bodega, that multinational bank was a local business, and you could rent a one-bedroom apartment for under $2,000.

Depending on your politics, income and connection to a place, such changes can be a welcome sign of new amenities and safer streets, or symptoms of a kind of urban cancer. And few places in the city reflect such trends more in recent years than the neighborhoods of northwest Brooklyn. Take a walk through Fort Greene, Clinton Hill or Bed-Stuy today and you’ll barely recognize the world filmmaker Spike Lee immortalized two decades ago in his classic “Do The Right Thing.”

“The Gentrification of Brooklyn: The Pink Elephant Speaks” brings together more than 20 artists to inspire thought and conversation around these seismic shifts in New York’s fastest-growing borough. Centered at the Museum of Contemporary African Diasporan Arts in Fort Greene, the four-month-long project combines art exhibitions with discussions, a play, a poetry reading and other events to reach beyond black-and-white diatribes and polarizing prescriptions.

Hence the project’s title, which invokes a metaphor commonly used for the delirium induced by heavy drinking. But Dexter Wimberly, who curated the exhibit, explains that “the ‘pink elephant’ is also just an older version of the ‘800-pound gorilla.’ It’s that large, looming thing that’s in front of everyone’s face but no one wants to acknowledge it.”

The works on display at MoCADA and the Adriala Gallery, a satellite space in Bed-Stuy, offer a multimedia experience that blends large-scale photography, works on paper, video, sculpture and street art to address the complex issues surrounding gentrification. All of the artists in the exhibit have roots in Brooklyn, and their dedication to the borough pervades the intimate spaces of MoCADA and Adriala both.

The exhibit does not preach or present one single view of Brooklyn’s gentrification. Instead, the works create a kind of visual dialogue, reflecting the diversity of experience and personal histories of their artists. But the show’s real stars are the voices of lifelong Brooklynites that comprise two audio installations at MoCADA, a piece of an ongoing project titled “Housing is a Human Right” that also includes photography, live events in New York and other cities, and a robust website.

Michael Premo, the artist behind that project and co-producer of “The Gentrification of Brooklyn,” says that he wanted to provide a space for people to tell their own stories. “We realized [that] can be very empowering,” he says, and the “Housing” project allows them to reach a larger audience than they may have thought possible.

“Storytelling is about empathy,” Premo adds. “You empathize with the story, and the same is true of organizers. I’ve always been an activist, and I realized very quickly that art is a very effective way to reach people.”

Premo, who grew up in Fort Greene and returned 10 years ago after stints in Albany and Boston, remembers when the neighborhood had almost a small-town vibe. “Fort Greene in the 80s and 90s had a very bohemian art culture,” he says, a far cry from the “mad-dash for development” he sees there now: “It’s gentrification on steroids.”

Cities evolve, of course, and none of the artists in the show are against change, per se. Nor is Dexter Wimberly, 36, who grew up in Bed-Stuy and Bushwick, but has also lived in more “upscale” areas like Brooklyn Heights. “I’ve devoted my life to art and artists, but I’m also very proud of Brooklyn’s legacy and its strength,” he says. So it was both a challenge and an honor, he adds, to incorporate so many different perspectives while paying homage to the borough that he has called home all his life.

Still, there is a consensus opinion in the show: gentrification, as it exists today, is bad. “There’s a big difference between community-based development and top-down development,” Premo says. “It’s one thing for a group to migrate into a neighborhood and start opening business. It creates the wonderfully rich eclecticism that allows the city to be speckled with all the continents of the world.”

It’s another thing, he adds, to let go of your sense of ownership and place, and give it over to corporate concerns. “Everyone has the right to a safe, secure home,” Premo says. “But there are barriers that prevent people from having that basic right met.”

The works that comprise “The Gentrification of Brooklyn” address those barriers, but do not dwell on them. The exhibit also captures Brooklyn’s ongoing vitality, its diversity, and its creative spirit. Together, they create an urgency in the show, a sense that the pink elephant cannot be subdued with art alone. With the controversial Atlantic Yards construction site looming just beyond MoCADA’s front door, “The Gentrification of Brooklyn” sounds a quiet alarm, one that grows louder the longer you listen.