Photo by: Jarrett Murphy

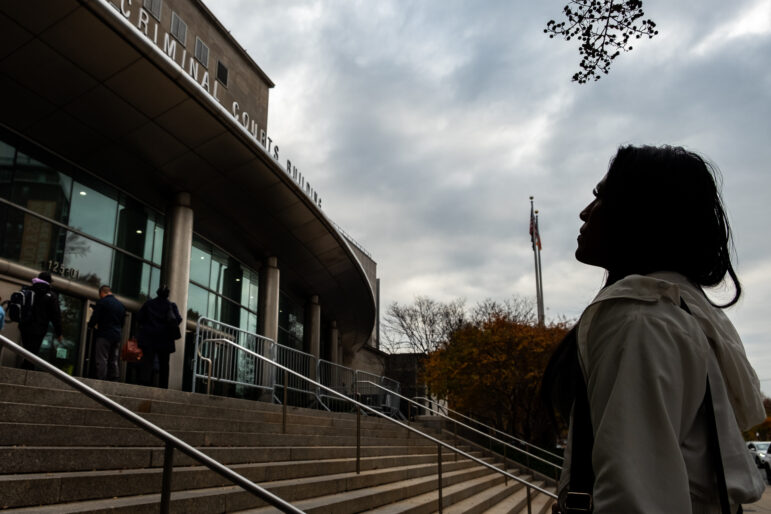

The Post stoked outrage when a bail clerk recommended releasing a now-notorious serial killer on his own recognizance.

The New York City Criminal Justice Agency (CJA) is a private, nonprofit organization that contracts with the City of New York to provide information to judges on whether criminal defendants are likely to appear in court if they are released before trial. An outgrowth of the city’s 1960s bail reform movement, CJA interviewers question defendants awaiting arraignment about their ties to the community, and check their rap sheets for indications of other open cases or a history of “bench warrants,” which are what judges issue when somebody misses a court date.

Using a point system, the CJA interviewer then generates a score for each defendant. That score translates into a recommendation that CJA gives to the judge. Some defendants are recommended for release on their own recognizance (ROR). Some are dubbed to be a “moderate risk” of failing to appear in court, while others are deemed “high risk.” For a few, however, CJA makes no recommendation at all as a matter of policy—a policy that is in some ways the work of David Berkowitz, a.k.a. Son of Sam.

On the morning of August 11, 1977, a few hours after he was arrested and as he awaited his arraignment in Brooklyn, Berkowitz met with a CJA interviewer named Harold Raines. The killer gave his name, nickname (“Son of Sam”), place of work (Bronx General Post Office at 149th Street) and home address. He said—truthfully—that he had never been arrested before, had never skipped a court date, wasn’t on parole or probation. When the interview was done, Raines followed procedure and stamped Berkowitz’s form “Recommended for ROR Based on NON-Verified Community Ties.”

Understandably, the judge rejected that recommendation and sent Berkowitz—who had admitted to killing six people and wounding several others in a year-long spree of violence—for psychiatric screening behind bars. When the story of the CJA recommendation leaked, there was an uproar. On August 19, the same day it endorsed Ed Koch for mayor on its front page, the New York Post headline was “Sam Bail Row.” Mayor Abe Beame said it made him wonder “whether judges, confronted with busy courtroom calendars, are accepting recommendations that permit dangerous criminals to walk the streets on little or no bail.” Then-Deputy Mayor Nicholas Scoppetta (the present-day fire commissioner), told reporters, “According to [CJA’s] procedures, they did what they normally do. But, following their procedures, they achieved an absurd result.”

Immediately, the head of the CJA—which had been operating with little fanfare in city courts for 16 years—said the agency would no longer make recommendations in homicide cases, although it would give judges information on the defendant. That policy stands to this day.