HHS

A display at the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services’ 2016 Ryan White conference.A new disease is cropping up in clusters around the world and rapidly killing thousands. It’s contagious, but affects different groups of people differently. Cities are especially hard hit. In the U.S., the federal government fumbles badly; at first denying the severity of the pandemic, then dithering on its response, and failing to heed the recommendations of public health experts or to invest resources wisely.

Sound familiar? For those who remember the early days of HIV/AIDS, today’s crisis has an eerie echo. Despite important epidemiological differences between COVID-19 and HIV, lessons learned and strategies developed during the HIV epidemic can help us develop policies to combat COVID-19.

The HIV crisis taught communities to care for their own. Then, as now, some governors and mayors led effective government responses in the face of a failing federal response. The more effective response both then and now has come from communities mobilizing to meet the needs, whether through AIDS service organizations and activist groups like ACT UP in the 1980s or mutual aid organizations today.

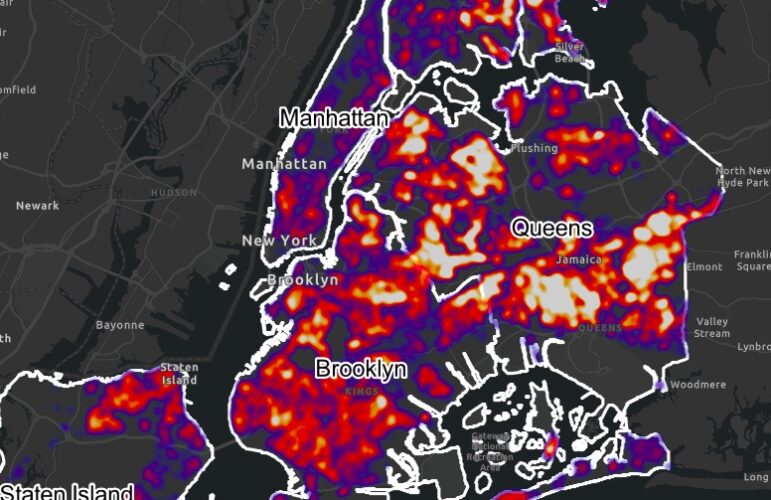

Unlike the early days of the HIV epidemic, the federal government is providing funding to mitigate the health and economic impacts of COVID. However, these federal stimulus funds have not effectively targeted the localities that are most in need, nor do localities have the power to apply funds to the needs specific to their areas.

To address these gaps, we suggest adapting a funding allocation process born during the HIV epidemic to meet specific community needs during the current crisis: The Ryan White CARE Act. Passed by Congress in August of 1990, that piece of legislation provided funding to increase access to health and social services for lower-income HIV-positive people. Funds were allocated to mayors or county executives in hard-hit metro areas based on the number of HIV cases.

Crucially, it also created local HIV Health Services Planning Councils that were empowered to make decisions about where federal funds were most needed in their communities. These planning councils still exist today and are comprised of healthcare providers, community-based AIDS service organizations, hospitals, government officials, and other crucial stakeholders.

CityViews are readers’ opinions, not those of City Limits. Add your voice today!

CityViews are readers’ opinions, not those of City Limits. Add your voice today!

Like the original, our proposed funding legislation around COVID would move new federal investment into the most affected metro areas and create local planning councils that would decide where the funds are needed most. The planning councils would be responsible for quickly creating plans based on data and evidence from public-health agencies to support crucial services ranging from housing to legal services, food, and child care. Local organizations would apply to the planning councils for access to federal funds through a streamlined procurement process.

This model would need to be adapted for the particular challenges of the COVID-19 epidemic. For instance, FEMA would have to be involved in the local planning councils in order to tap their vast disaster response resources. Funds would target those known to be at greatest risk of COVID-19 exposure, including essential workers; people with chronic or immune-suppressing conditions; and people in congregate settings including correctional facilities, homeless shelters and nursing homes. Funds would also go towards services for other groups whose life circumstances are untenable in light of the epidemic, including people who are homeless, living in overcrowded conditions, and people who had worked off the books but are now ineligible for unemployment benefits.

To ensure that planning councils can effectively target funds to local needs, the federal legislation should have few restrictions and new funds should not supplant existing funding streams. Local communities may choose to fund priorities like boosting safety in congregate settings; providing palliative care support at home; supporting volunteer mutual aid networks; helping business owners keep their employees; providing child care centers and home schooling assistance for essential workers; or developing supportive housing for homeless people with COVID.

Congress needs to act as boldly today as it did in 1990 to ensure that stimulus funds are reaching the Americans most in need. That requires meaningful, structured, and ongoing input from the most affected communities.

To get our society back on its feet, we need to mount a herculean effort quickly without leaving behind people who are vulnerable and severely affected by this pandemic. Let’s look to a valuable lesson from the past to help guide us out of this crisis.

Dr. Ruth Finkelstein is a professor of urban public health at Hunter College, CUNY and the director of Hunter’s Brookdale Center for Healthy Aging. She has a background in public health, grounded at the start of the HIV/AIDS crisis, the last major epidemic changing the future of the world.

One thought on “Opinion: A Lesson from the AIDS Crisis for Dealing With COVID-19”

Gee, I thought I was the only person dealing with COVID as I did with the first wave of AIDs.

I lost 30 in ten years. Oh I remember all right, I sure remember. Yeah this is pandemic is feeling all too familiar.