“Embracing nature-based solutions, leaning on digital tools to power water management, replacing aging infrastructure, and, importantly, fostering collaboration between city agencies and private partners are essential to tackle these challenges head on.”

Michael Appleton/Mayoral Photography Office

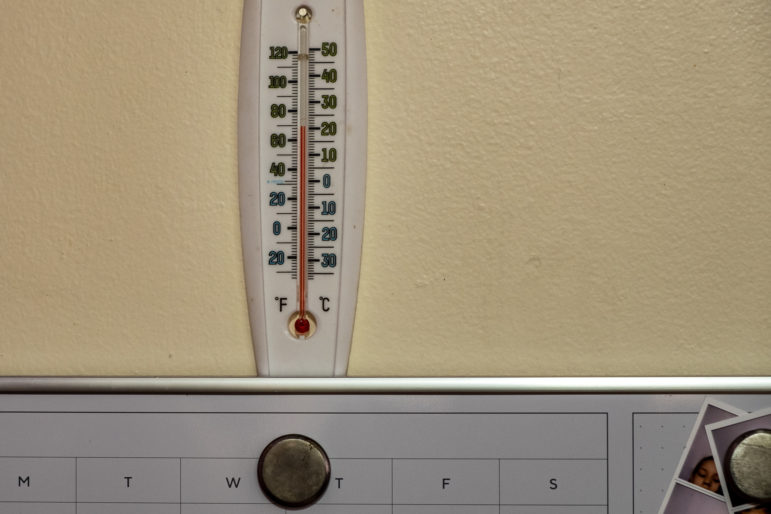

Dry conditions in a NYC park in November 2024, when the five boroughs were under a drought watch.For the first time in over two decades, New York City was under a drought warning late last year as our watershed dipped to dangerously low levels. The historically dry conditions stand in stark contrast to the year before, when New Yorkers endured eight consecutive weekends of heavy rain, with our streets turning into rivers and neighborhoods being flooded.

These extremes highlight an uncomfortable truth: managing droughts and floods are two sides of the same coin. Both crises, while opposite in their nature, are intensified by climate change, extreme weather patterns, and aging infrastructure.

However, floods and droughts having similar drivers means that the approaches to addressing both also overlap. Embracing nature-based solutions, leaning on digital tools to power water management, replacing aging infrastructure, and, importantly, fostering collaboration between city agencies and private partners are essential to tackle these challenges head on.

One of the most promising ways to address both droughts and floods is by turning to nature. Cities around the world are adopting nature-based solutions that capture, store, and release water. For instance, increasing a city’s “sponginess” through permeable surfaces like parks, rain gardens, and tree canopies can absorb excess rainwater during storms, reducing the risk of flooding. At the same time, these interventions can also recharge precious groundwater reserves.

Technology is another powerful tool to improve how we manage floods and droughts. Particularly with green infrastructure, technology can help us to identify places where such interventions would be most effective. Furthermore, machine learning and predictive models can help the city better anticipate where stormwater might overwhelm infrastructure.

For example, the Department of Environmental Protection piloted a program called FloodNet, a series of flood-monitoring sensors around the city, which will allow us to respond more effectively to flooding and implement measures such as temporary barriers. Pushing ahead with such innovations might look like creating a citywide system that maps the health of our water infrastructure in real time.

During droughts, sensors and AI-powered monitoring systems can help detect leaky pipes or excessive water usage in specific buildings, allowing us to target vulnerabilities and conserve resources. This information can also help New Yorkers make informed decisions about their own water use. To drive individual action, New York could implement an incentive program where households or businesses that stay under a certain usage threshold earn credits, like existing solar energy programs that allow users to sell excess power back to the grid.

While we may not have all the resources to tackle everything at once, we can apply solutions that —due to their co-benefits—are greatly effective in their system-wide contexts. In other words, with holistic thinking and planning, seemingly small steps can lead to big change.

Examples of such interventions that solve more than just one issue include stormwater storage tanks on individual properties that not only ease pressure on strained sewer systems by capturing heavy rainfall, but also support droughts and water shortages by doubling as a reserve. Larger scale projects, like our work on the Kensico Eastview Connection, an aqueduct project that links water facilities to supply water to the city and Westchester County, can be tailored to address priority concerns such as ensuring redundancy and efficiency in our water systems.

Finally, at the heart of these feats of technology and engineering are the people working to create and drive them. The work to address floods and droughts can’t happen in silos. Managing water in a city as complex and densely populated as New York requires collaboration across government agencies and the private sector. While the Department of Environmental Protection leads much of this work, impacts to our water affect every corner of city government and city life, from transportation to housing to emergency management.

The city has started to leverage public-private partnerships to unlock creative solutions and reduce the financial burden of building a more resilient urban environment. Continuing to bring the bigger picture into view and increasing such partnerships across other agencies will be essential to ensuring that stakeholders can identify linkages earlier in the process and address all possible impacts.

As the past two years have shown, floods and droughts are not faraway threats—they are imminent in New York City. These interconnected crises demand action, and it will always be the right time to accept our shared responsibility to invest in solutions and practices that protect all New Yorkers.

Through nature-based solutions, digital innovation, and purposeful, collaborative governance, we can build a water system that serves all New Yorkers, today and for years to come.

Ozlen Ozkurt is Americas East Water Business Leader at Arup.