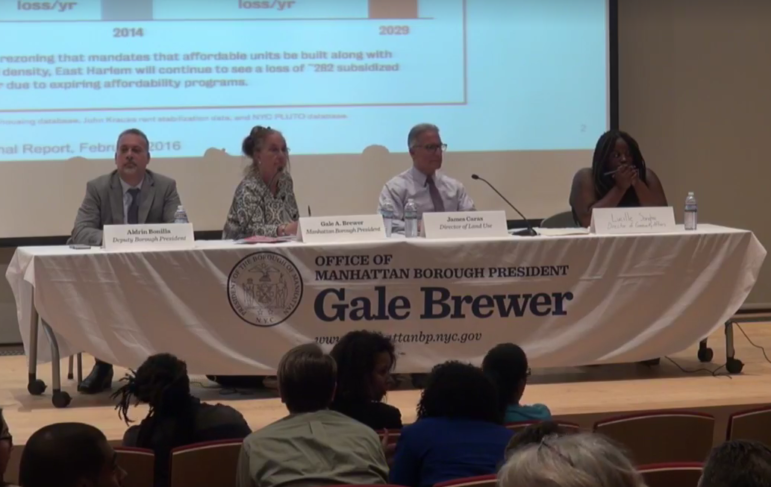

From City Limits Livestream (Marc Bussanich)

Manhattan Borough President Gale Brewer and her staff at a hearing on the East Harlem rezoning, July 13 2017.

Nearly everyone who testified at Manhattan Borough President Gale Brewer’s hearing on Thursday said the city’s rezoning plan for East Harlem would greatly exacerbate the displacement of neighborhood residents and should be prevented.

The big question facing Brewer, as she decides on her recommendation over the next few weeks, is not whether to object to the city’s current plan, but to what degree to object, and with what alternative in mind.

The city has proposed upzoning several neighborhood avenues in East Harlem to encourage housing development, with a portion of units rent-restricted under the city’s mandatory inclusionary housing policy. The plan would do other things as well, such as limit the heights of buildings on certain blocks and require space for transit infrastructure.

It is the third of the mayor’s rezoning plans to make its way through the public review process known as the Uniform Land Use Review Procedure (ULURP), which begins with a community board vote and is followed by a borough president, City Planning Commission, and city council action.

The community board’s June decision to disapprove “with conditions” the city’s rezoning has already become a source of neighborhood controversy. Those conditions, which can be viewed here, include more affordable apartments, a number of anti-displacement initiatives and strategies to improve economic opportunities in the neighborhood, and a less dense rezoning mirroring the one proposed in the East Harlem Neighborhood Plan spearheaded by Speaker Melissa Mark-Viverito, among other measures.

But others have argued that any kind of rezoning will result in gentrification—and that only a sound “no”, without conditions, will fail to put a stop to the city’s plan.

Concerns and alternatives

At Thursday’s hearing, many testifiers reiterated this point.

“I don’t know who they listened to. It clearly wasn’t the 98 percent of people who came to the mic and said ‘no with no conditions,’“ said tenant advocate and resident Pilar DeJesus, referring to the board’s decision. She said that instead of a rezoning she would recommend the city pass tougher laws to protect existing rent-stabilized tenants from predatory landlords. As for creating new housing, “stop building in communities of color,” she said. “I don’t know why it has to be here.”

Others who testified said the plan would benefit developers, not residents, and a few drew parallels to ethnic cleansing. Over 20 members of the Movement for Justice in El Barrio attended the meeting to demand an unconditional no and that the mayor’s plan be swapped for their 10-point-plan focused on revamping the Department of Housing, Preservation and Development (HPD), penalizing bad landlords and conducting a massive tenant outreach campaign, among other measures. About ten people from the Justice Center en el Barrio marched to the hearing to deliver another resounding no.

Other alternatives to a rezoning presented by speakers included more investments in NYCHA, identifying more parcels of public land where low-income housing could be built, enacting policies to stop property owners from warehousing their buildings, and ensuring the long-term affordability of existing affordable housing by transferring buildings into the East Harlem Community Land Trust. Some of these alternatives—like a tax on warehousing, and more funding for NYCHA—are also suggested in the full community board response to the rezoning.

Shantal Sparks, a representative for the community board, emphasized the board’s many concerns with the city’s plan and said their conditions—such as 100 percent affordability on all public land—are meant to encourage the city to take the issue of displacement more seriously. Board member Nilsa Orama added some ideas not included in the board’s conditions, such as support for community land trusts and housing for the homeless.

Marcel Negret, speaking on behalf of the Municipal Art Society of New York (MAS), was one of several analysts who took issue with the city’s Environmental Impact Statement (EIS). He said there are 521 multi-family residential buildings in the rezoning area that are “underbuilt,” or smaller than what existing zoning allows, and that a rezoning could create additional development pressures at these sites. The EIS, however, excludes 66 percent of these sites from their predictions of development under the rezoning, which MAS fears may result in an underestimation of how many people might be displaced from existing buildings in the area.

Not allowed to vote just no?

Jarquay Abdullah, one of the roughly ten community board members who voted down the motion for “no with conditions,” brought up the fact he was not allowed the option of voting on a motion for ‘no with no conditions’ at the June board meeting.

According to an accounting of events explained to City Limits by both Abdullah and board chair Diane Collier, Abdullah asked Collier in the midst of the chaotic June 20 board meeting whether he could motion for an amendment from “no with conditions” to “no” before a vote was taken. She did not think this order of operations was permitted under board rules, and said that first the board members had to take a vote on whether or not to support “no with conditions.”

According to multiple experts in parliamentary procedure, it’s possible the chair made an error in that ruling, although the matter is not clear-cut. Under Roberts Rules, a member of the board is allowed to move for an amendment to “strike out” part of an original motion, so Abdullah changing “no with conditions” to “no” seems like it should have been alright.

On the other hand, board members are not supposed to amend a motion so much that he or she could just vote against the original motion to achieve the same result—and what’s “so much” is certainly a matter for debate.

In any case, if Collier had allowed the motion to amend, it would still have required the board members to vote to adopt the amendment of the strike-out. There’s no way to say how many board members would have supported that.

And board members are allowed to dispute a chair’s decision—so Abdullah or someone else could have motioned to appeal the chair’s decision on Abdullah’s amendment. In reality, however, the June 20 meeting was too chaotic for this to happen, and the board’s vote on June 27 to adopt its original decision makes the matter somewhat moot.

While arcane, the questions of procedure could be relevant to other community boards grappling with rezonings that generate multiple strands of opinion and passionate protest.

Brewer stresses preservation

For her part, Brewer opened by acknowledging the differences between the city’s plan and the East Harlem Neighborhood Plan. She also stressed her concern that the city was not doing enough to measure and to address the potential loss of existing affordable units.

The borough president said she agreed that the city’s Environmental Impact Statement had underestimated displacement, called the Certificate of No Harassment program heralded by advocates “important,” and repeatedly asked questions of testifiers to gather ideas about preservation strategies. And throughout the night she took a gracious tone, often allowing people to go over their allotted times. “I’m probably not supposed to say this, but I love the signs,” she said, regarding the many anti-rezoning poster boards decking each side of the room.

Towards the end of the hearing, however, members of Movement for Justice in El Barrio accused her of pretending to listen to the community while planning to vote “no with conditions.” They also said they had tried repeatedly since 2015 to contact her about their 10-point plan and their position on the rezoning, and had been repeatedly ignored. Brewer said she hadn’t received any notice they were trying to contact her, would be glad to meet with the group, and would be in touch the following day.

Asked by City Limits after the hearing whether she had thoughts on whether there should be a more modest rezoning or no rezoning at all, Brewer emphasized her concerns about preservation, but said she wasn’t ready to make a statement about a rezoning.

“I need to look a this more carefully,” she said.

Brewer, who must make a final recommendation by August 2, will accept written comments until July 24, and possibly longer if appropriate; comments can be sent to atigani@manhattanbp.nyc.gov. Both the community board and the borough board recommendations are advisory, with the ultimate decision made by the City Planning Commission and City Council.

Darlene Jackson, staff member for Community Board 11, asked us to share her testimony on the importance of community engagement in the ULURP process. Pearl Barkley has also shared her testimony regarding her concerns with a rezoning and the steps that must be taken to protect low-income residents. Want us to share your hearing testimony with the public? Send it to zone@citylimits.org and we’ll post it.

9 thoughts on “East Harlem Rezoning Hearing: Residents Beg Brewer to Vote No”

I think Harlem needs the help that’s coming and no one can stop it. It’s long over due . Harlem is one of the riches neighborhood, rich in culture and in money and believe me the money is here. I attend the meetings and everyone that’s crying out about displacement take a look at them, see what they are wearing add the price of there outfit that’s not displacement, that’s wanting to continuing living on system. It’s time people if you have been living in an affordable apartment since you were a child and now you are an adult with your own family with grand kids don’t you think buy now you should have moved out of the projects and have a home of your own. I listen to people say that there parents lived in the apartment they lived in and now there kids live with them and grand kids. When is this going to stop. I think affordable living should be for the vet’s and the elderly, not the one’s that are working and driving BMW’s and Benz. These vehicles are even parked in the housing parking lot. Come on people don’t blame the landlord for wanting to sell out to investors because I’m sure if your money did not go back to PR or DR to purchase that big house that you are making money on you would have spent it here and then you could have sell to an investor and you would be one of those landlord that you are calling slumlords. People Harlem is changing and you can’t stop it what you can do is get off the gravy train and start doing something for yourselves. I’m a immigrant migrated from South America. When my parent’s came into this country we never heard about affordable living. My parents worked there butt off to put food on the table and keep a roof over our head. Today I have two son’s one is a mechanical engineer and the other is a civil engineer and l raised my kids to reach for the the sky and people if you continue to live the way you do you will have nothing. Maybe that’s what you want the community board and the city consul members to think. Maybe if they feel sorry for all you that will be displaced then you all could laugh behind there backs and say we got them exactly where we wanted them and we won. I think the city is very smart and they have been looking at this for over ten years and crying wolf now wont help so get use to it. I think you all should start by bringing back some of that money you sent back to your native land because you will need it for the rent increase no more $800 a month rent.

Your approach is (once again) rather presumptuous. “The big question … is not whether to object to the city’s current plan, but to what degree to object, and with what alternative in mind.” That’s NOT the ONLY option, as thousands of concerned citizens have been chanting all along. Our elected representatives DO have the power to just say NO to ANY rezoning. P.S. The only “beggars” here are all the 2017 candidates panhandling the Real Estate industry. Rather off-putting that you fail to research and report on whose campaign coffers are being lined by developers and property owners ready to blow up East Harlem and 14 other low-income communities of color.

Ah, it’s semantics time again! “To what degree to object” would to any fair reader encompass saying no altogether. The only option our language forecloses, actually, was saying an unconditional “yes” to the city’s plan. That is the only thing that seems totally off the table.

The primary definition of “beg” is “to ask (someone) earnestly or humbly for something,” an an earnest asking is what seems to have gone on here.

That’s not what the Mayor meant when he chastized people (earnestly) ask for help on the streets. The timing in your choice of synonyms seems a bit “off-putting” considering, wouldn’t you agree?

“Beg” is a poor word choice for the title of the article. Its a real condescending way to snub the local resident voice which seems pretty unified and clear

The only “beggars” involved in this mess are all the 2017 candidates panhandling the Real Estate industry. Rather off-putting that the media fails to research whose campaign coffers are overflowing with handouts from all the developers and property owners ready to blow up East Harlem and 14 other low-income communities of color.

Pingback: News (July 2017)

The fact of the matter is that places that allow lots of new housing (e.g. Raleigh, Houston) have low rents. Places that don’t (e.g. New York) have high rents. So it is the absence of housing that causes gentrification and displacement, NOT the presence of housing.

The people not heard at the meeting are the many thousands of immigrants and young people who need the housing the rezoning will permit.

I’ve lived here for 70 years. NYC did not use to be so selfish. It’s time for us old timers to let go.