“Can I love and support a family member who was harmed by someone experiencing homelessness and also be against the unnecessary and unjust killing of an unhoused person?”

Emma Whitford

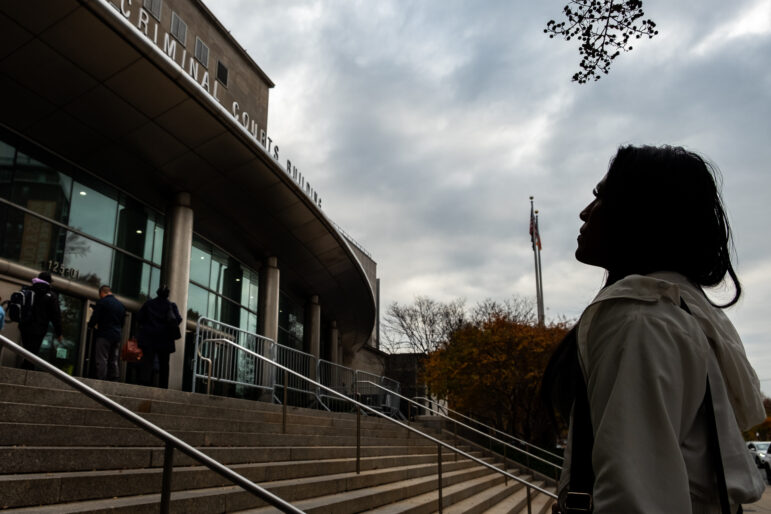

A vigil for Jordan Neely held in City Hall Park in May 2023.Foreshadowing: While I sit at the living room table, reading a jury duty summons, a TV news anchor announces the start of jury selection for the trial in which, “Daniel Penny is accused of killing a homeless man.” More than a year after his death and despite the viral video of him being fatally choked, Jordan Neely is still “a homeless man.” They didn’t even say his name. It’s shocking—what happened in that newsroom, and what happened this week in the jury room.

After news of Penny’s acquittal sets my phone notifications abuzz, I think back to that jury duty summons. I imagine being a juror on the Penny trial. When you put together 12 of anything — disciples, days of Christmas, jurors—there’s a need for balance. My unique perspective would’ve helped keep the scales of justice level. Maybe the injustice of the Penny verdict wouldn’t feel so weighty.

Prior to the start of jury selection in the Penny trial, a relative (let’s call them Anon) dropped a heavy and incendiary text into the family group chat: “A stance against Penny is a stance against me.”

Anon is pro-Penny—although it comes across as anti-valuing the life of Neely—but I get it; as an imaginary juror, I can find middle ground amongst polar opposite positions. (Although, in this time of divisiveness, I’m becoming a polar bear—balancing on a small piece of glacial ice—my middle ground is eroding like the Arctic.)

Anon is the victim of a recent violent attack: a person who is experiencing homelessness hit them in the head with a metal pole. Pictures are posted in the family group chat. There’s a laceration (great enough to be visible but not great enough to require stitches) and the blow did draw blood, but it didn’t necessitate a trip to the hospital.

I want to respond to Anon, but it’s complicated. A meme or GIF is inadequate. In order to be empathetic, fair, and not unduly swayed by love for family or duty to advocate for the unhoused, I ponder my multi-viewpoint response:

1) I have experienced homelessness.

2) I have experienced a rough day on the subway, on the verge of a meltdown, threatening other passengers: I told the “Showtime!” breakdancers that if I get hit in the head (again) by an errant Adidas shell-toe sneaker, “I’m opening up a can of whoop ass on the whole crew.”

3) I have been put in a chokehold and suffocated until I lost consciousness. Many moons ago, in a group home, a fellow resident—without consent—turned my neck into a testing site for The Cobra Clutch, the signature finishing move used by the wrestler Sargeant Slaughter.

4) I have used violent force in a public transportation setting against a “homeless man.” He was a fellow resident in the men’s shelter where I resided. I used violent force against him in order to save a life.

People see it differently, how to save a life. The jury that acquitted Penny saw it as a chokehold—one that prosecutors said lasted almost six minutes (which is about two minutes longer than the song “How to Save a Life” by The Fray).

When I had to save a life it looked like being a passenger on the M35 bus, watching the driver get choked by a “homeless man.” My fellow shelter resident (let’s call him nonA) became incensed when the driver didn’t open the door after already pulling away from the curb. He jumped in front of the bus and prevented us from moving forward. After a momentary stare-down, the driver relented and (against MTA policy) opened the door.

nonA boarded the bus, stopped at the fare box, and (instead of swiping a Metrocard) sucker-punched the driver in the face.

The driver defended himself valiantly—against someone twice his size with twice the muscles— but still ended up in The Cobra Clutch. The driver clawed at nonA’s arms the way Neely clawed at Penny’s. I could see the driver’s eyes gasping for air.

The driver began to lose steam—or maybe consciousness. There was less fighting back and more going limp. Was I witnessing the actual taking of a life? In violation of the New Yorker code (mind your business), I went against MTA policy (Stand Behind White Line): I limped into the restricted area with urgency and struck nonA in the head with my cane.

You can never tell how things will go when you hit someone in the head with a metal object. A single blow from a pole or cane can result in a mild laceration (that doesn’t require suturing) or have a deadlier ending.

LET HIM GO! (nonA doesn’t let go.)

I strike him in the head with my cane.

LET HIM GO! (nonA still doesn’t let go.)

I strike him again in the head with my cane.

GET THE F*** OFF HIM! (I’m not a death expert, so I can’t say the driver is dying right before my eyes. I can only say that I watched a massive heart attack kill my grandmother and what’s happening to the driver looks worse.)

I strike nonA in the head with all my might.

They say the third time’s the charm. After blow number three, nonA lets go of the driver. Then he pivots toward me. I stand face to face with fear. I feared for the driver’s life, now I’m scared for mine.

But I did not swing my cane a fourth time. Once the danger to the driver ended, the Good Samaritan cane-swinging ended. nonA looked at me (after being hit in the head with a cane full force) and he said, “Thank you, sir. Have a nice day.” We all exited the bus (MTA policy). When a driver is choked, the bus is no longer in service.

The next day, in the shelter cafeteria, I overheard a conversation about what transpired on the M35 bus. They said nonA did a few tours in Iraq. He was wounded in combat and has a metal plate in his head. (Maybe you’re asking yourself the same question I asked myself: Is there a correlation between chokeholds and military service?)

Serve with me as an imaginary juror. I’ll even let you be the foreperson. Can we find middle ground? Yes, Penny acted in self-defense. Yes, he played the role of Good Samaritan. But he went too far. Let’s ask the judge if we can re-watch the video: Count how many minutes elapsed while Neely, in a nearly empty train, offering less and less resistance until devoid of movement, is kept in a chokehold. Can we agree that Penny should’ve released Neely much sooner?

According to the New York City medical examiner, the chance that Neely died from anything other than Penny’s chokehold is “vanishingly low.” Penny should not have made Neely’s life vanish. Can we agree on that? If not in a real jury room, then at least in this imaginary one?

The trial is over. Daniel Penny walks (over Jordan Neely’s dead body, again, but this time figuratively). I stop imagining myself a juror.

I start wondering: What if I was on that F train? Would Penny have let go of Neely, if I yelled, “Let him go! Let him go! Get the f*** off him!” Would I be forced to swing my cane? If I hit Penny in the head—because it’s the only way to make him end the chokehold—and his attention is now solely on me, what happens next? Maybe I’ll ask this in the family group chat.

I think I now know what I want to say in the family group chat: Can a stance against perpetrators of violent assaults coexist with a stance against someone who unilaterally plays the role of judge, jury and executioner? Can I love and support a family member who was harmed by someone experiencing homelessness and also be against the unnecessary and unjust killing of an unhoused person? Justice for Neely, accountability for Penny, caring about public safety—these are not mutually exclusive.

M.A. Dennis is an advocate, poet, and survivor of homelessness.