“CityFHEPS vouchers are meant to make life easier for tenants and their families facing eviction, or those families who have been previously unhoused, by paying ongoing rent. That sounds great on paper, but far too often the slow pace of the system renders the vouchers useless.”

Gerardo Romo / NYC Council Media Unit.

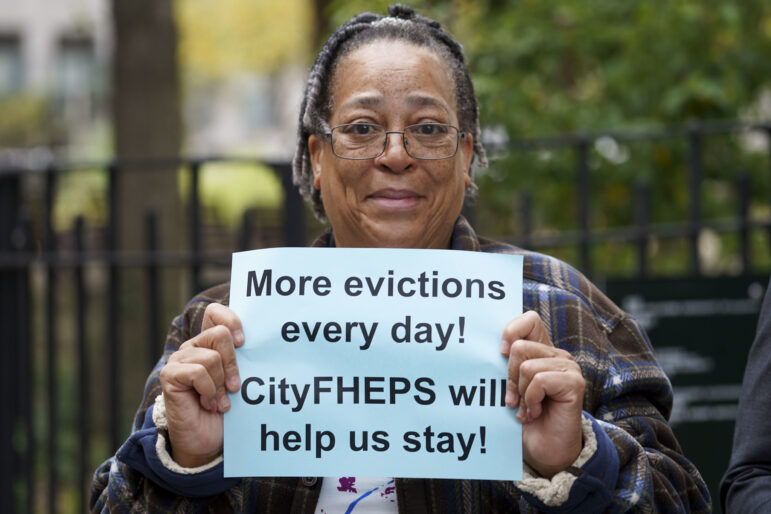

Housing advocates and councilmembers at a rally outside City Hall to call for expanding CityFHEPS.For New Yorkers hoping to take advantage of a housing voucher, timing is everything. It is no secret that finding any type of housing in New York City is difficult: vacancies are low, demand is high, and rent is through the roof. As of June of 2023, only 33,000 out of over 2 million apartments were available to rent. This does not even take into consideration what the most vulnerable New Yorkers face.

We work at Brooklyn Legal Services Corporation A (Brooklyn A), a non-profit law firm providing free civil legal services to New Yorkers across the city. Our Preserving Affordable Housing (PAH) team works to keep people in their homes through eviction defense, securing rental assistance, assisting tenant associations, and, when necessary, helping clients relocate with housing vouchers. The City Fighting Homelessness and Eviction Prevention Supplement (CityFHEPS) vouchers are meant to make life easier for tenants and their families facing eviction, or those families who have been previously unhoused, by paying ongoing rent. That sounds great on paper, but far too often the slow pace of the system renders the vouchers useless.

Consider the case of our client who we’ll call Rose (a pseudonym). A mother of two who receives a CityFHEPS subsidy, Rose has a CityFHEPS shopping letter—a document that a tenant uses to search for apartments which shows how much rent CityFHEPS will pay for a place—but has only six months to find a new apartment that will accept her voucher and process everything. Otherwise, she and her children will be forced to enter the shelter system, or else be out on the streets. The clock is ticking for her to find an eligible apartment in a city with record-low vacancies, while caring for her 13-year-old and infant child whose birth came the very same day as Rose’s court appearance for her holdover proceeding.

These kinds of intensely stressful situations are far too common in New York City. From what we’ve seen, it’s the product of a complex process with several pinch points that waste valuable time for voucher holders. Many Brooklyn A clients have struggled to find alternative housing despite having a CityFHEPS shopping letter, citing delays from city agencies meant to support tenants seeking housing.

CityFHEPS is most commonly obtained through Homebase, a program meant to provide homelessness prevention services. New Yorkers that may qualify for Homebase services must seek appointments to have their cases and situations evaluated. This screening process should be relatively easy, or at least expedite things, but in Brooklyn, prospective clients’ names are taken down on the call list and told that it may be up to eight weeks before they hear back.

That’s precious time with no traction for Brooklyn A clients. After this delay, there may be even further delays in the application process—a CityFHEPS application is lengthy, requiring a mountain of paperwork documenting income, public benefits, leases, shelter residency letters, and so much more. Homebase then works with NYC’s Human Resources Administration (HRA) and the Department of Homeless Services (DHS) to provide eligible clients with the shopping letter, which many clients report they need to start their search for affordable housing.

Once an apartment has been found, DHS, HRA and Homebase then need to coordinate the processing and inspection of said apartment—another area of delay, since inspections need to pass to allow for a CityFHEPS recipient to move in. If it doesn’t, it’s back to the drawing board for clients, who are quickly running out of time to move. Brooklyn A clients aren’t the only ones struggling to make use of housing vouchers. A report from the New York State comptroller’s office last month concluded CityFHEPS is “plagued with problems” that include delayed rental payments and poor documentation within the shelter system.

This certainly holds true, as Brooklyn A staff have seen many nonpayment cases where our clients are confused—for one reason or another, CityFHEPS stopped paying rent, racking up thousands in rental arrears. Recertification processes were unclear and lengthy, causing lapses and delays in payments as well. The system is unclear and counterintuitive. Not only do tenants have to be near-perfect with timing, but they have to do so while navigating a nebulous system with red tape and runaround.

Uncooperative landlords pose another roadblock: the city recently reached a settlement with Parkchester Preservation Management after an investigation revealed that thousands of tenants with housing subsidies were blocked from renting an apartment. This kind of income discrimination, where landlords refuse to accept tenants who use government aid to pay rent, persists for our clients and countless others across the city.

New York has a responsibility to its residents. Mayor Eric Adams’ office and the City Council have often butted heads over the CityFHEPS program. Late last year, the Mayor’s office and DSS announced that they were focused on improving technology to streamline these vouchers, with clients being able to recertify for their vouchers through the ACCESS HRA App. This doesn’t account for the fact that the recertification process can be lengthy and arduous, with a single mistake on an application having long-term problems. It also doesn’t account for bugs, glitches, or problems within the system.

Vulnerable New Yorkers are working hard to provide for their families and need a roof over their heads to be safe and secure, and New York City needs to step up and provide better support to these families—and it needs to happen now.

Rukhsar Asfe is the supervising social worker in Brooklyn A’s Preserving Affordable Housing: Brooklyn program, and Kameal James is a paralegal for Preserving Affordable Housing: Brooklyn.

2 thoughts on “Opinion: It’s Time to Fix CityFHEPS Vouchers”

These kinds of intensely stressful situations are far too common in New York City. That’s sad to hear

I’m 62 years old I’m retired and I need a goddamn place to live get up off your asses and do your f****** jobs