A report that projects the impact of sea level rise on the U.S coastline ranked New York as the ninth state with the most critical infrastructure at risk of flooding in 2050, and the sixth in 2100.

Adi Talwar

A person paddle boarding on the Hudson River.Sea level rise driven by global warming is on track to put critical New York buildings —like public housing complexes, hospitals, schools and power plants—at risk of frequent inundation, a recent study by the Union of Concerned Scientists found.

Rising sea levels bring on high tides and amp up the intensity and frequency of coastal storms, both of which lead to flooding.

The report, which looked at nearly 1,100 assets along the U.S. coastline, ranked New York as the ninth state with the most critical infrastructure at risk of flooding in 2050, and the sixth in 2100. For the mid-century mark, Louisiana came in first place and New Jersey in second.

In New York, 55 crucial sites could be at risk of flooding, on average, twice annually by 2050. Of those, 39 would be at risk of flooding once a month and 34 could flood once every other week, the report says.

By the end of the century, the number of critical locations at risk of flooding twice a year could jump to 374. Of those, 281 would be at risk of flooding once a month and 253 once every other week.

These projections aren’t even based on a worst case scenario. They assume a medium rate of climate-driven sea level rise, based on the estimate that the oceans will rise at a global average of 3.2 feet by 2100.

Juan Declet-Barreto, a senior scientist at the Union of Concerned Scientists who helped author the report, says the looming deadline should be a call to action.

“Policymakers and governments need to be using the latest and best science on sea level rise impacts to plan for coastal resilience and create policy that will lead to good adaptation and that won’t ignore the problem,” he said.

Local officials have been racing to protect New York City’s 520-mile shoreline from the rising sea. “Since 1900, sea level in our city has risen 12 inches and is projected to continue to increase by as much as 6.25 feet by 2100,” a Department of Environmental Protection (DEP) spokesperson said in an email.

To tackle the issue, the city has added over 13,000 green infrastructure assets, like rain gardens and storage tanks, that collect water when flooding occurs to keep sewers from overflowing. Starting in 2026, all city-owned infrastructure and public facilities will be required to meet a stringent set of design criteria to better withstand extreme weather.

There are also attempts to raise entire plots of land that are vulnerable to flooding. The East Side Coastal Resiliency project, for instance, seeks to elevate lower Manhattan’s East River Park by approximately eight feet and install “flood protection in the new space beneath it,” according to the DEP.

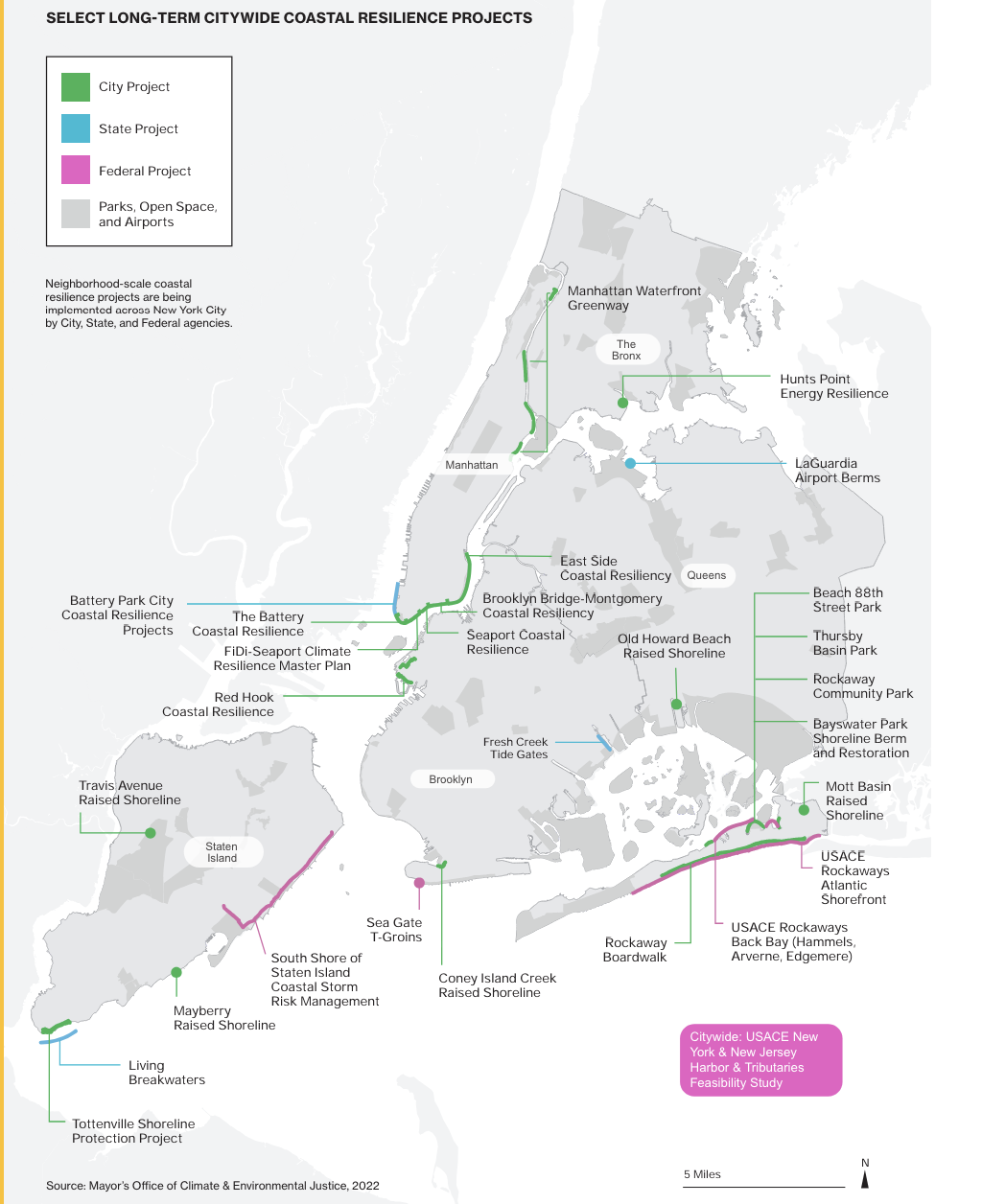

This resiliency effort is one of at least 10 city-led projects that aim to use floodwalls, land elevation and floodgates to keep water out. But of these 10, the DEP says only three have started construction.

Mayor’s Office of Climate and Environmental Justice

A map of planned coastal resiliency projects.Meanwhile, federal plans led by the Army Corps of Engineers to barricade the city from coastal storms with over 82 miles of floodwalls, levees and deployable gates are yet to leave the drawing board. And environmentalists claim the plan has major pitfalls.

“The Army Corps project to date has not incorporated sea level rise as one of the problems that they are trying to solve,” said Kate Boicourt, director for the Climate Resilient Coasts and Watersheds team at the Environmental Defense Fund (EDF).

These barriers, Boicourt says, are designed to close the city off when a storm hits and won’t prevent impacts from sea level rise that are progressive and long term. Failing to address that could put the lives of New Yorkers at risk, environmentalists warn.

“It can mean losing access to power and losing things that electricity provides to people like food, heating and cooling. It means people might be pushed out of their homes without having anywhere to go,” said Victoria Sanders, the climate and health programs manager at the NYC Environmental Justice Alliance (NYC-EJA).

“It can mean all sorts of really devastating consequences for a lot of New Yorkers, but especially for those who are most vulnerable,” she added.

To reach the reporter behind this story, contact Mariana@citylimits.org. To reach the editor, contact Jeanmarie@citylimits.org

Want to republish this story? Find City Limits’ reprint policy here.

One thought on “By Next Century, Hundreds of Critical NYC Buildings Risk Frequent Flooding: Study”

Better double those estimates after adding in subsidence and delayed infrastructure fixes, especially in land-fill areas like Alphabet City. On the other hand, the NY Times just this week had an expose’ on how the low lying Maldives are NOT sinking as predicted; the shorelines are just shifting with some up and others down, but overall no change.

The coastlines will do what they’re going to do before the political divide heals.

Our large RiverArch development project could have been a small part of the solution, but we couldn’t get the land.

– Scott Baker

CEO RiverArch Ventures, LLC