Mayor Eric Adams has positioned the Atlantic Avenue Mixed-Use Plan as one of two significant neighborhood-level rezonings that could help boost his “moonshot” goal of 500,000 new units of housing over the next decade.

Adi Talwar

Apartments on Grand Avenue and Pacific Street, included as part of a walking tour of the AAMUP area in April. The new residential building is the product of a one-off rezoning application.A low-density corridor through Central Brooklyn recognizable for its body shops and storage facilities could see about 4,000 new apartments under an early zoning proposal released Wednesday, up to 38 percent of which could have income-restricted rents.

Wednesday’s virtual meeting marked a step forward in a complex mixed-use rezoning plan for Atlantic Avenue between Vanderbilt and Nostrand avenues and surrounding blocks, touching Crown Heights, Prospect Heights, Clinton Hill and Bedford-Stuyvesant.

“It’s a draft,” said District 35 Councilmember Crystal Hudson ahead of the presentation. “It will most likely be further modified as we move through the process, and there are going to be multiple opportunities for revisions and modifications.”

Mayor Eric Adams has positioned the Atlantic Avenue Mixed-Use Plan (AAMUP) as one of two significant neighborhood-level rezonings that could help boost his “moonshot” goal of 500,000 new units of housing over the next decade, alongside a proposal for the East Bronx around two forthcoming Metro North stations.

“We’re entering a more technical phase, and kind of putting pen to paper in terms of, what is the specific zoning we’re considering,” said Jonah Rogoff, lead planner on the project with the Department of City Planning (DCP), at Wednesday’s meeting.

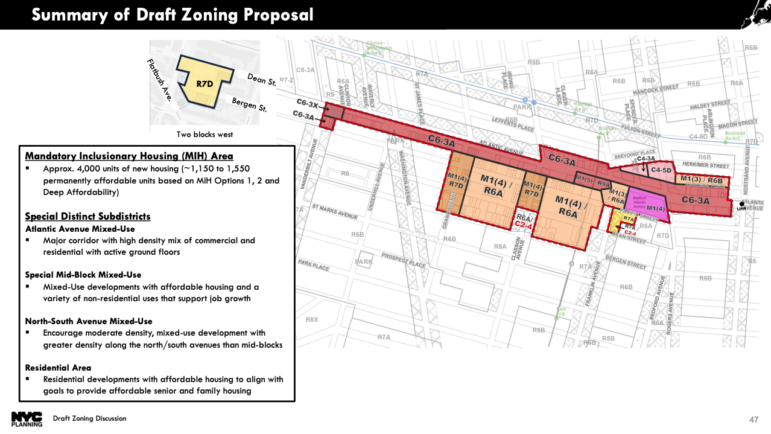

The draft proposal calls for high density along Atlantic Avenue—up to 185 feet, or about 18 stories—with apartments above ground-floor retail. Avenues running north-south below Atlantic would be zoned for moderate density up to 125 feet, sandwiching “mid-block” areas with incentives for both housing and jobs, including manufacturing.

The area also includes the Bedford-Atlantic Armory, which will continue to house a 350-bed men’s shelter, though the city is taking recommendations for additional uses, such as a library or healthcare facility. Three city-owned sites on Dean, Bergen and Pacific streets are set aside for deeply-affordable apartments for families and seniors.

Dept. of City Planning

A map of the proposed rezoning area.The AAMUP area has been zoned M1-1 since 1961, according to the city, allowing for low-density commercial and industrial properties.

But site-specific residential rezonings have begun to crop up in recent years—despite comprehensive planning efforts by Community Board 8 stretching back a decade—prompting Councilmember Hudson to help renew the push for a larger-scale rezoning last year with an emphasis on affordable housing.

Now a major east-west route for trucking, Atlantic Avenue was a freight train route in the 1800s, connecting Long Island farms to the Brooklyn waterfront. The Long Island Railroad still runs below the rezoning area, and has a station at Nostrand Avenue.

The AAMUP zone is also walkable to the A and C subway lines and seven bus routes. Transportation hubs like this would have to increase their housing production under Gov. Kathy Hochul’s so-far-unsuccessful statewide plan, and are also a development priority for the Adams Administration.

“This is an area where there’s been a lot of pressure because [nearby] rezonings have limited growth, and it’s very transit-rich,” said Liz Denys of Flatbush, a mid-Brooklyn chapter leader for the pro-development group Open New York. “I think there could have potentially been opportunity for even more housing, but it’s a really great start.”

“I think as much affordable housing as possible is a great goal, and I think the way we achieve it is by ensuring cross-subsidization programs that make it possible for people to build those deeply affordable units,” Denys continued.

But Wednesday’s presentation was met with frustration from several locals, who were doubtful that the affordable units will actually be affordable to people who live in the area.

“All the land-use moving forward should be for low-income housing only,” said Sharon Kinney, a local broker. “If this city truly cared about its citizens and the poor people that have been displaced by the greedy landlords, then that’s what they would do.”

“I’ve been living on Eastern Parkway facing the [Brooklyn] Museum for 50 years,” she continued. “My community flipped from brown and Black people to predominantly white.”

The city’s own analysis shows displacement from the AAMUP area. Blocks within a half mile radius saw 12 percent population growth between 1990 and 2020, to about 119,000. In the same period, the Black population dropped about 50 percent, to less than 39,400, while the white population increased more than 300 percent to 49,349.

According to Wednesday’s proposal, developers would have to adhere to citywide Mandatory Inclusionary Housing (MIH) options, established in 2016. A DCP spokesperson said the specific options will be determined later in the process over the next half year or more, though “Option 2” is currently being considered, among others.

Option 2 sets aside 30 percent of apartments for families earning an average of 80 percent of the Area Median Income (AMI), or $101,680 for a family of three. By contrast, Option 1 requires that 25 percent of units be affordable to those earning an average of 60 percent of the AMI, or $76,260 for that same family. The “deep affordability” option requires 20 percent of units be set aside at 40 percent AMI, or $50,840.

The median household income within AAMUP’s half-mile radius is $106,500, according to the city, compared to $67,800 in Brooklyn as a whole.

Gib Veconi, a member of Community Board 8 as well as the AAMUP steering committee, said he expects developers to choose the second option, which caters to higher income tenants, if given the choice.

“DCP can say they are going to map deep affordability to give developers the option, but developers are not charities,” he told City Limits. “They have to make a return on their projects, and they are going to pick an option that gives them a higher return.”

In 2018, Community Board 8 released a report laying out its goals for the area, including affordable housing subsidized by more expensive apartments, and manufacturing jobs for locals that wouldn’t require a college degree.

A plan for the M-CROWN district, which stands for “Manufacturing, Commercial, Residential Opportunity for a Working Neighborhood,” ultimately didn’t proceed—though it drew support from Adams, who was borough president at the time.

Veconi said the community board had sought incentives for light industrial use in the M-CROWN area, while the new plan emphasizes a residential and commercial mix. “The zoning they presented last night will drive all of the industrial uses out of the zone,” he predicted. “I would expect things like retail and hospitality and perhaps some office space. Especially stuff like coworking.”

According to DCP, attendees at recent public planning sessions requested housing in spots where previous iterations of the plan would have blocked it.

Adi Talwar

The Department of City Planning hosted the second Atlantic Avenue Mixed-Use Plan (AAMUP) meeting at the Fort Greene Council Grace Agard Harewood Neighborhood Senior Center on April 16.Ahead of Wednesday’s meeting, the city released a summary of feedback collected at 12 public events between January and June, co-hosted by DCP, Hudson’s office and planning firm WXY Studio.

The report details six main priorities, including deeply affordable housing and protections for existing low-cost homes, street safety improvements, green spaces, walkable jobs and support for minority-owned businesses.

Next week, DCP said it will put out a scoping notice—a prerequisite to a review that delves into impacts on the environment, including air quality and traffic. The multi-month Uniform Land Use Review Process, or ULURP, is expected to kick off next spring.

Sarah Lazur, a member of Community Board 8 and the Crown Heights Tenant Union, said she had been holding out hope for a zoning proposal with affordability that went deeper than MIH. Already, she said, union members are experiencing displacement pressure from landlords who are “thinking aspirationally” about the rezoning.

“It sounded to me like [DCP was] saying, ‘Oh, we heard you that affordable housing is important, and that will be accomplished by MIH,’’’ she told City Limits. “And that’s completely missing the point.”

Deeper affordability levels would require citywide reform to MIH, Sarit Platkin, director of neighborhood planning at the Department of Housing and Preservation Development, told meeting attendees Wednesday.

“What you’re referring to are issues that are bigger than this neighborhood alone and this rezoning alone,” she said.

To reach the reporter behind this story, contact Emma@citylimits.org. To reach the editor, contact Jeanmarie@citylimits.org.