A coalition of groups representing undocumented immigrant workers, cash earners and others excluded from traditional worker benefits are campaigning for a stronger social safety net for these employees, who they say were essential to keeping New York running throughout the pandemic.

Courtesy Make the Road New York

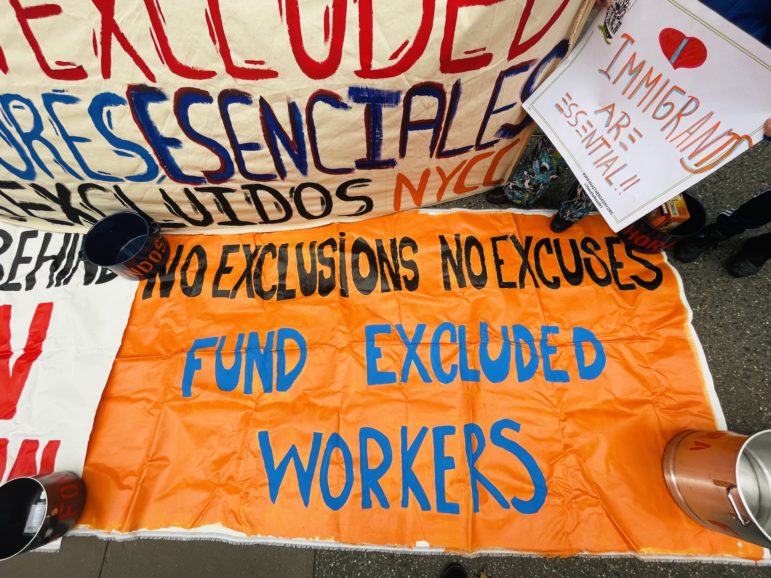

Members of the Fund Excluded Workers’ coalition rallied in Manhattan Wednesday.

Last year, New York activists and organizers went on a weeks-long hunger strike urging the state to set aside funds for hundreds of thousands of low-income workers, including undocumented immigrants, who were locked out of COVID stimulus payments and unemployment benefits, despite losing work during the pandemic.

Their resulting victory was a landmark $2.1 billion, included in last year’s state budget, for New York’s Excluded Workers Fund, among the first in the nation to provide relief payments to workers who otherwise didn’t qualify for government-issued pandemic aid.

Now, as the coronavirus crisis continues into its third year, organizers are pushing state lawmakers to not only replenish the fund—which ran out of cash and closed to new applicants about two months after opening—but to provide a more permanent social safety net for these types of workers, including access to health care and unemployment coverage.

“Our communities are often left to fend for themselves,” Nova Rivera, an organizer with the Fund Excluded Workers Coalition, told City Limits. “We do need to make sure that all workers have protections, and have a social safety net for workers to fall back on when there is a crisis…especially workers that kept the state going [during the pandemic.]”

At rallies held across the state on Wednesday, New Yorkers employed in a range of professions—including house cleaners, nannies, laundry workers, food service employees and street vendors—shared stories about their experiences during the pandemic, and organizers rolled out a platform of state bills they’re targeting for passage in the upcoming legislative session.

The groups are pushing for Gov. Kathy Hochul to budget $3 billion to refill the Excluded Workers Fund, which gave out one-time payments to New Yorkers who lost income because of COVID-19 but were ineligible for federal stimulus payments and other relief aid. The fund opened in August and approved payments for 130,145 people, the vast majority of whom received the highest tier of funding: $15,600.

The state closed the program to new applicants on Oct. 8, saying the $2.1 billion budgeted for it had run out. Advocates hailed the program as “life-changing” but say demand for it far exceeded available funds. Just about 37 percent of the total claims the state received for the initiative were approved, according to Department of Labor data.

“[It] just showed that the need is incredibly high,” said Rivera.

Some Republican state lawmakers have resisted calls to replenish the fund, and Hochul’s executive budget, released earlier this week, did not specifically earmark money for the program. But the governor did allocate $2 billion for open-ended “pandemic recovery initiatives” and said she plans to work with lawmakers to determine exactly where that gets spent.

“Governor Hochul has made it a priority to get relief to excluded workers as quickly as possible,” Jim Urso, a spokesman for the governor, said in a statement. “With session now underway, the Governor will continue to work with legislators, community and advocacy partners to support immigrant communities and vulnerable New Yorkers.”

The Fund Excluded Workers Coalition has some ideas on that front: Their platform is additionally calling for the state to establish a permanent program to provide unemployment insurance benefits for those who can’t qualify for existing government unemployment—primarily undocumented workers and those who get paid in cash.

They’re proposing a program that would use similar eligibility and documentation requirements as the Excluded Workers Fund. For example, a worker who can’t apply for traditional unemployment because of their immigration status would qualify for the “Excluded No More” benefits as long as they earned less than $56,000, and worked at least 20 weeks, in the year before they lost work. Organizers estimate that $800 million in state funding would allow such a program to cover a $1,200 monthly payment to 50,000 people.

“We can’t rely on temporary fixes,” Rivera said, saying that while the Excluded Workers Fund was a successful tool, it doesn’t address the gaps in the government’s safety net system that existed long before the pandemic. “Once folks go through their funds, if they’re still out of a job…they’re just back where they started.”

The coalition is also pushing for the passage of four state bills it says would help vulnerable workers: to legalize street vendors in larger cities across the state, strengthen enforcement against labor violations, raise wages for tipped workers like restaurant servers and provide health care coverage to New Yorkers who are insured because of immigration status.

“We are in a time of crisis where we cant leave any workers out,” Rivera said. “Our recovery is interconnected—when we leave some workers out, it damages all of us. It damages the state’s recovery.”