A lack of translation services has complicated access to healthcare and financial aid for the many thousands of Latin American people who speak neither English nor Spanish.

El Diario

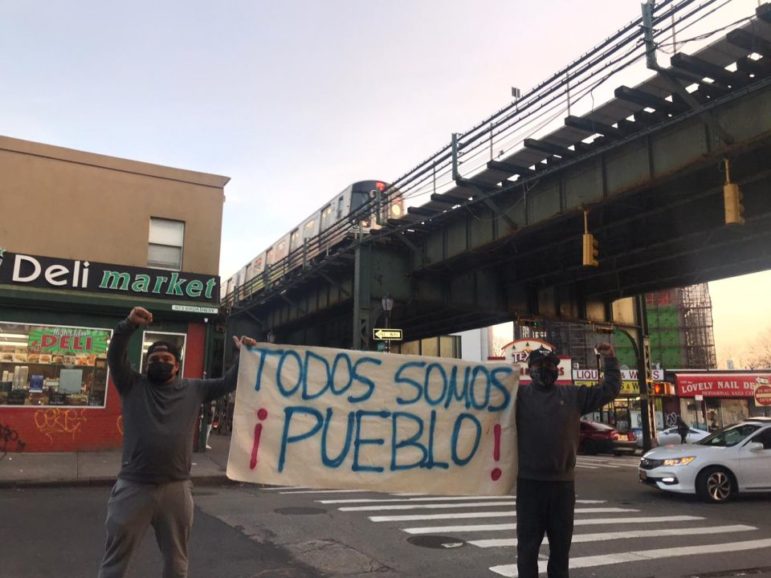

Indigenous people from Latin American countries living in New York demonstrated to demand protection for their communities.This article originally appeared in El Diario

Translated by Carlos Rodriguez

In the midst of the second wave of COVID-19, which has left over 20,000 dead in New York City and inflicted massive harm to the finances of thousands of low-income families, indigenous immigrants from Latin American countries gathered on Friday to raise their voices and demand protection for their communities.

Convened as the New York Indigenous Immigrants Assembly, dozens of indigenous people, activists and political and community leaders gathered to ask the state and local governments to include them and give them the treatment they deserve as city residents.

Their demands include that consulates offer more services in their native languages, further protection for food delivery workers and the approval of higher taxes for the wealthy, which would pay for benefits for excluded workers.

“We, the indigenous communities, have been excluded from the aid offered to other fellow immigrants. For us indigenous people who speak original languages, it has been more complicated to access medical services in this city,” said Yoloxochitl Marcelino, born in the Montaña Alta region of the Mexican state of Guerrero. “Because we do not speak the language or understand it well, we have no access to interpreters, we are considered ignorant, and we are unable to obtain adequate services.”

The activist, who speaks Tu’un Savi, a Mixtec language, estimates that there are more than 200,000 indigenous immigrants in New York City despite the Mexican Consulate’s official figure of 35,000. Most of them work in restaurants and delivering food, she added.

State Assemblywoman Carmen De La Rosa joined the demonstrators in their demands, asking for the acknowledgment of the rights of indigenous immigrants. She added that many of them have lost their jobs during the pandemic and have been left out of assistance programs.

“As legislators, we cannot look the other way regarding the most vulnerable among us, particularly indigenous immigrants, who are essential workers and are being excluded. Today, we call on Governor Cuomo to listen to our plan and tax multimillionaires to create a fund for excluded workers,” said the lawmaker.

State Senator Jessica Ramos joined the plea to pass higher taxes for the wealthy and grant these groups the protections they need.

“Indigenous immigrants live in the intersection between being essential workers and excluded workers. Their work creates wealth for our state. In New York, we have more multimillionaires today than before the pandemic. Together, they are worth more than $500 billion and have made close to $77 billion more in the last few months,” said the legislator. “Asking those 120 people to contribute to a fund that will provide $23 billion in tax revenue is really a negligible change for them but can contribute to improve the lives of thousands of New Yorkers. It is the right thing to do, and the sooner we do it, the faster we will prevent a bigger economic calamity.”

Saul Quitzet, who sells flowers in New York City and survived COVID-19, said that his community endures rejection every single day.

“For our people, including indigenous people who got sick and turned to hospitals for help, it was very difficult to receive treatment. There is no serious commitment to have interpreters and translators in hospitals, or to distribute information among our community about the pandemic, the law or financial assistance programs,” said Quitzet. “There is no respect for our language, our customs or our worldview. We are treated as pawns who are only good for work.”

Angeles Solís, a lead organizer with Make the Road New York, demanded that indigenous immigrant communities are given access to basic protections.

“The pandemic has significantly affected immigrants and working class New Yorkers, including our indigenous brothers and sisters. These communities are struggling to put food on the table and continue to face enormous rental bills,” said Solís. “Once again, and before the year ends, we demand protection for delivery workers, access to language services, and immediate action to increase taxes to multimillionaires to fund excluded workers.”

One thought on “NYC’s Latin American Indigenous Communities Demand Protection”

The reality of the systematic exclusion of indigenous immigrants is a disgraceful national issue in the United States. It starts at the US SW border where Spanish speaking Border Patrol agents systematically ignore indigenous immigrants and their languages. The five children that died in Border Patrol custody in the past two years were all indigenous peoples with parents whose primary language was an indigenous Mayan Language. A disproportionate number of separated children from immigrant parents are indigenous children.

We need a Congressional investigation into why Executive Order 13166 is not being implemented, and indigenous language rights are being denied. After they leave the border – they are never counted as indigenous peoples – only as “Latinos”.

The exclusion and discrimination of indigenous identities and indigenous languages by US DHS agencies at the US-Mexico border has been denounced by the American Congress of American Indians and the Cherokee Nation in separate resolutions. In cities all across the United States (Phoenix, LA, Oakland, Houston, Dallas, South and Middle Florida, fives states of Southern rural Appalachia, N. Carolina, and the Washington D.C. to Boston Corridor {DC, Philly, New York, and Boston} they live unseen and unheard.

Major metropolitan and state health departments refuse to even post or use COVID prevention messaging (like the State of Arizona) in indigenous languages like these: https://www.indigenousalliance.org/landing-page . An exception is Lincoln Co. Oregon.

Elected representatives need to direct public health agencies to cooperate with grassroots indigenous organizations. We have documented that 20% of immigrants crossing the border are primary indigenous language speakers. Please contact us.

Indigenous Languages Office,

Alitas Shelter, Tucson, Arizona