NYC Council

Bronx Councilmember Vanessa Gibson (file photo) says she has received calls about senior residents found already passed away in their NYCHA apartments. ‘It’s overwhelming. It’s emotionally draining to try to coordinate services for families.’As an increasing number of reports reveal COVID-19 is having a disproportionate impact on low-income, majority minority areas of New York City, leaders in the South Bronx and in other communities have been demanding a more targeted response.

City data sets first made available last week show geographic disparities in case numbers and death rates. As of Wednesday morning, Bronx residents made up 26 percent of the New Yorkers who have died from COVID-19, though the borough is home to only 17 percent of the city’s population. According to zip-code level statistics from Tuesday, the top five neighborhoods with the highest number of positive cases were Corona, Borough Park, Elmhurst, the Norwood and Olinville sections of the Bronx, and Midwood—impacting areas with some of the city’s large immigrant communities as well as areas with large Orthodox Jewish communities. (Health experts, however, caution that statistics are an artifact of how many people have been tested and not fully reliable)

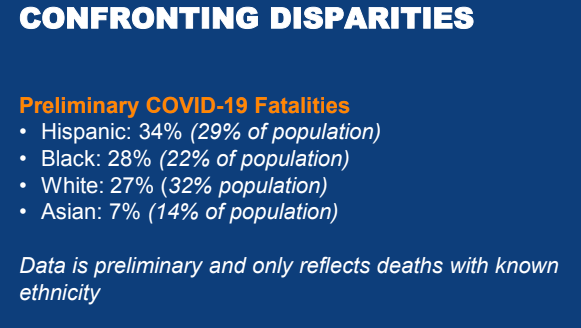

Now, after much public pressure, the city has also released COVID-19 fatalities broken down by race and ethnicity, revealing that Black and Latino New Yorkers make up 61 percent of the virus deaths in New York City though they make up 51 percent of the population. After adjusting for age, Black and Latino New Yorkers have about twice the fatality rate as White New Yorkers. (Race and ethnic data is available for 63 percent of currently reported deaths.)

While the state hospitalization rate appears to be slowing down—increasing three percent since yesterday instead of 25 percent as in weeks past—it remains unclear whether this means New York is hitting its peak or is experiencing just a temporary flattening. There also remains the threat that individual neighborhoods will experience much later peaks.

Some advocates in the southern and western Bronx have been calling for the use of vacant available land in their districts to increase medical infrastructure. Pushing back on the idea that asking residents to stay home will be enough to stop the crisis, they have called for increased investments in information campaigns, COVID-19 testing, struggling local health centers, food access programs and other resources.

“Between the city and state, we have got to give priority to the South Bronx, to the West Bronx,” said Bronx Councilmember Vanessa Gibson on Tuesday, explaining she had received calls about senior residents found already passed away in their NYCHA apartments. “It’s overwhelming. It’s emotionally draining to try to coordinate services for families.”

Similar demands were expressed by councilmembers in other boroughs reached by City Limits on Tuesday, while some also lamented that more steps were not taken earlier to prepare low-income neighborhoods for the impact of COVID-19. They also emphasized that, post-crisis, the city must prioritize impacted low-income communities of color, and deeply commit to overcoming existing health and economic disparities.

“We’re anticipating cuts to the city, but we should ensure that those cuts are not to the poorest New Yorkers. We need to make sure we are preserving food access, benefits, building more affordable housing,” says Councilmember Donovan Richards, representing southeast Queens. “We need to double down on these things.”

On Wednesday, both Governor Andrew Cuomo and Mayor Bill de Blasio separately announced new plans to address the racial disparities of COVID-19’s impact. The mayor said he’d continue to push for resources for the city’s public hospitals, launch a multi-million dollar public awareness campaign reaching New Yorkers in 14 different languages and focusing on communities of color and zip codes with the highest positive cases, increase “grassroots outreach” to New Yorkers, and expand 311 so New Yorkers can have more detailed conversations with health care workers and receive more specific medical advice.

The governor also announced a plan for a multi-lingual awareness campaign to reach all New Yorkers, including hard-to-reach communities. The campaign will include initiatives like a flyering campaign to educate New Yorkers who are not online and partnerships with media to create print, radio and video ads in multiple languages, among other steps. He’s also called for additional research into a viral spread in minority communities and has vowed to increase testing in minority communities.

“We are working with local elected officials and other community leaders, as well as healthcare providers, throughout the state on how best to continue our nation-leading testing efforts, to ensure everyone who needs a test can get on,” Jonah Bruno, a spokesperson for the State Department of Health, wrote in an e-mail to City Limits.

South Bronx demands more medical capacity

As has been earlier reported, Bronx residents have long had the worst health outcomes in New York State, making them greatly vulnerable to medical complications. As of Wednesday morning the city was reporting 936 Bronx deaths, of which 853, or 91 percent, were associated with underlying conditions like diabetes, heart disease, cancer, asthma and other illnesses—the highest rate of co-morbidities among the five boroughs. The South Bronx, in particular, with its high concentration of NYCHA developments, has long been recognized as a hotbed of environmental injustice concerns, with child asthma hospitalization rates three times the city average.

The South Bronx is currently served by Lincoln Hospital, which advocates say was already strapped for resources before the crisis began. According to NYC Health and Hospitals, the system has been transferring some patients from Lincoln to other public hospitals with more capacity, and is simultaneously expanding the hospital by several hundred beds. President Trump has also approved the use of the New York Expo Center, an event venue in nearby Hunts Point, for use as an emergency medical facility.

Some advocates say even with these additions, Lincoln Hospital is not likely to meet the growing need for emergency medical infrastructure in the South Bronx. Mychal Johnson, founder of South Bronx Unite and Mott Haven-Port Morris Community Land Stewards, argues that the most vulnerable residents should have access to care as quickly and close-by as possible. “Time is of the essence when you’re dealing with intensive-care issues,” he says.

On Monday, several officials called on the governor to convert the Harlem River Yards into a new 8-acre medical facility. They want the state-owned, 12-acre vacant industrial waterfront property converted into a field hospital, rapid testing center and barracks for emergency medical and military personnel.

“[That] we’re still not getting the equitable resources is really just a continued slap in the face that aligns with redlining, that aligns with race and justice issues that have historically plagued this area of the South Bronx,” says Brady. He also has concerns that the New York Expo Center site will not be sufficiently accessible—and is too close to a crucial food distribution center.

Similarly, Johnson along with Columbia public health professors Diana Hernández, Michaela Martinez and Markus Hilpert have called for the establishment of a portable hospital, naming St. Mary’s Park, Yankee Stadium or Harlem River Yards as possible sites.

The state Department of Health had no comment by press time on whether the governor would consider a South Bronx medical facility.

The role of local clinics

In many low-income communities, health centers have long played a vital role, providing holistic healthcare to Medicaid patients as well as the uninsured. According to the Community Health Care Association of New York State, federally qualified health centers serve a population that is 89 percent low income and 64 percent Black and Hispanic.

On Tuesday, Gibson told City Limits she wanted to see more support for health centers that still have their doors open, and more system-wide coordination between hospitals and local centers. “I don’t want to lose sight of the other healthcare [organizations] that can be partners. All they need is support; they need the Personal Protective Equipment (PPE),” she said. She said that if willing local clinics had PPE and test kits available, symptomatic Bronxites could get tested at a comfortable, familiar setting instead of needing to wait until they were in critical condition and needed to be hospitalized. “We don’t want to wait for that scenario to happen for people to get help.”

On Wednesday, the De Blasio administration announced that its new plan will involve local health centers in a grassroots outreach initiative.

“We’re going to have to work closely with community based clinics, where there are health care workers that have a deep sense of their own communities,” the mayor said. “We’re going to have to find a way to get health care workers out into communities to educate people, to answer their questions, to help them address their immediate challenges, but in a way that’s safe for those health care workers.” Like Gibson, he said empowering health care workers to directly communicate with neighborhood residents will require they have PPE. An exact plan, he added, would be developed in the coming days.

Many centers are now encouraging patients to stay home as much as possible and switch to telephone appointments. The Institute of Family Health, which has 34 locations in the city and Hudson Valley including six in the Bronx, says that their doctors are now completing almost 2,000 telehealth appointments per day, managing critical health needs while helping keep patients out of the hospitals. Yet because the state is not reimbursing phone appointments at the full rate, health centers could gradually become insolvent. The Institute has already had to lay off about 200 support staff and is concerned about the sustainability of the organization after 1.5 to two months.

“Does anyone think that it would be helpful if all these people ended up in the emergency room?” asks Dr. Neil Calman, President and CEO of the Institute.

Similarly, Paloma Izquierdo-Hernandez, president and CEO of Urban Health Plan, which operates mostly in the Bronx as well as in Queens and Harlem, says that they’ve closed three of their 12 health centers temporarily and are serving many patients remotely. Yet as a result of the conversion to remote appointments, the organization has faced a 50 percent drop in revenue, and are having to think about furloughing staff and holding back payments to vendors for non-essential services.

And another challenge of working remotely, says Izquierdo-Hernandez, is that while video appointments would be most useful, many patients—and many staff, to—lack computers or broadband.

The state Department of Health had no comment by press time on whether it would be able to reimburse clinics for telephonic visits.

Notably, not all patients have converted to phone visits. In another neighborhood with high levels of pre-existing health issues—Brownsville, Brooklyn—the Brownsville Multi-Service Family Center is transferring to telehealth appointments, but there is still a too-large subset of patients who don’t want telehealth appointments. These include patients who usually use the ER for primary care and now have reduced access to hospitals. As a result, the center was short on PPE until Wednesday, when they received a shipment that they predict will last a month.

Targeted resources

The announcement of city and state plans to address racial disparities follows advocates’ demands for a variety of other resources aimed at low-income, dense communities.

Johnson and the Columbia professors have called for increased testing for hardest-hit areas, especially for NYCHA residents with high risks of exposure and pre-existing conditions. They’ve also advocated for direct food and supply relief to housing complexes, improved WiFi access and increased public display of multilingual health information and resources.

Councilmembers Gibson, Rafael Salamanca and Diana Ayala called for increased testing sites in the South Bronx; Gibson named Yankee Stadium as a possible location.

Charmaine Ruddock of Bronx Health REACH at the Institute for Family Health, which advocated for reporting on racial demographics and a plan to address racial disparities, also stressed the importance of helping people who may not have regular internet access to receive accurate information and resources, as well as helping people learn about telehealth appointments.

Leaders in other boroughs have also called for a range of new, non-medical programs.

Councilmember Francisco Moya, who represents Corona, Elmhurst, and Jackson Heights, has called for an emergency relief fund to finance death arrangements for those who cannot afford it. While the city has a burial allowance program, the application requires a social security number—a barrier for many in his district.

Southeast Queens councilmember Richards is urging the city to build localized, accessible testing sites, increase investment in housing resources and food access programs, and increasing outreach for these programs to residents without internet access.

Manhattan Councilmember Ydanis Rodriguez is calling for the establishment of isolation housing so that people who live in crowded housing units can isolate themselves if they become sick.

“The Armory Track at 168th street and the United Palace, both of which are located in Washington Heights, have the capacity to properly house hundreds of New Yorkers. The dorms at City College and Columbia University should also be used as temporary housing,” Rodriguez wrote in a press release Tuesday. “As an entire nation pays attention to our response to this pandemic and look for guidance in our actions, we’ll be remembered for how fairly we treated our most vulnerable New Yorkers.”

3 thoughts on “Bronx and Other Hard-Hit Communities Cry Out for COVID-19 Resources”

I would like to know how seniors and people without a car can go get tested.seems like all testing sites are drive thru.its not fair for others who does not have a car.

The racial breakdown of deaths in nearly useless information, unless we also have a racial breakdown of positive cases to put the numbers in context.

How so?